We interview Frankie Shea, founder of Moniker Art Fair

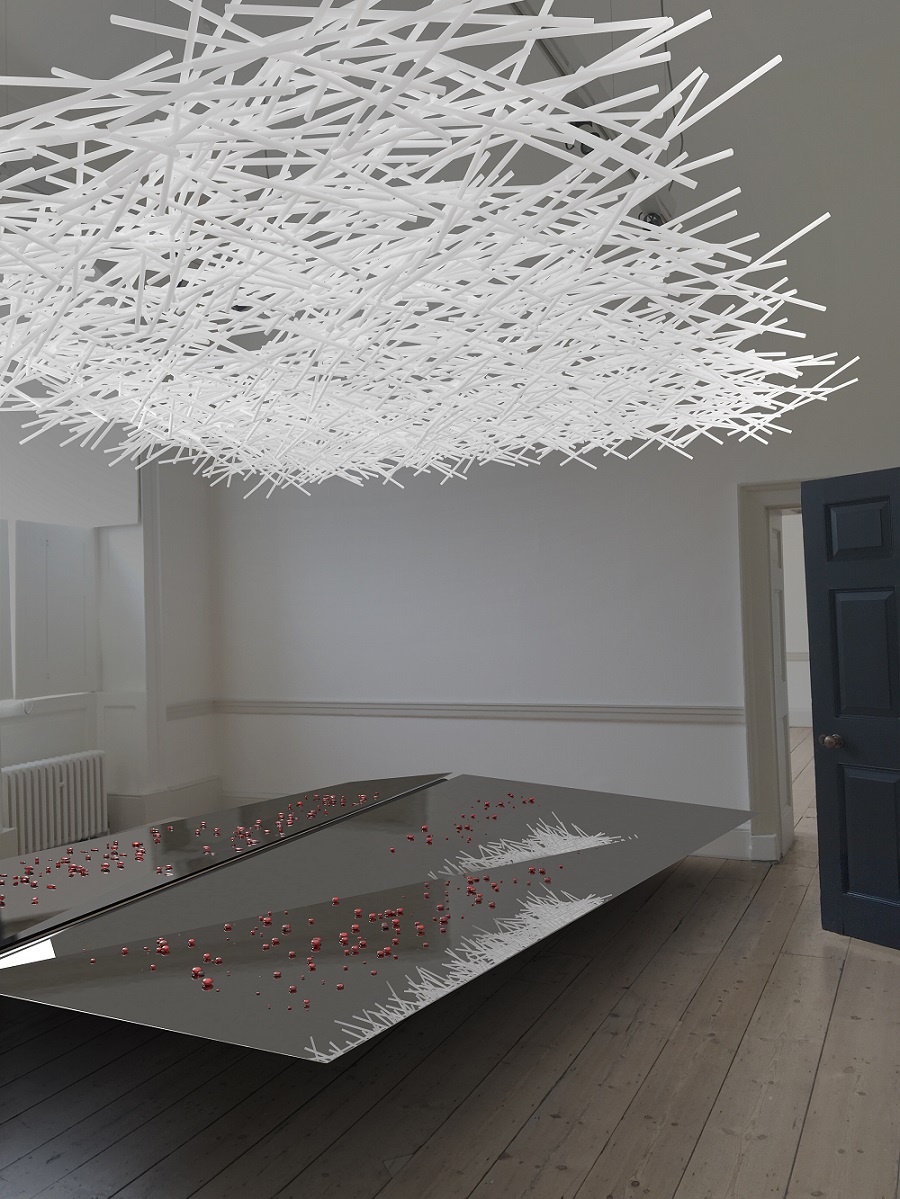

Moniker Art Fair returns for its sixth year, on October 15–18 at the Old Truman Brewery, having firmly established itself as London’s premiere event for contemporary art with its roots embedded in urban culture.

Moniker 2014

Moniker Art Fair returns for its sixth year, on October 15–18 at the Old Truman Brewery, having firmly established itself as London’s premiere event for contemporary art with its roots embedded in urban culture.

Building on the foundations of five years experience and it’s continued success, Moniker Art Fair will be again venue-sharing with London’s leading artist-led fair, The Other Art Fair, in what will be a showcase of independent and established talent all under one roof in East London’s iconic Old Truman Brewery.

This exciting spectacle will attract 14,000-plus visitors to the capital’s East End, forming one of the major satellite events of London’s Art Week when 60,000 visitors descend on the city to form an unparalleled international art audience. The partnership emphasises both fairs formidable reputations for showcasing artists operating under the radar of the traditional art establishment. Over a period of four days and across 21,000 sq. feet in The Old Truman Brewery’s impressive interior, this compelling combination promises to generate much interest and exposure this coming October.

BM - Why did you decide to start an art fair?

FS - The fair was started out of frustration.

I was running a gallery and representing several artists within the street art genre with great success. The artists I worked with had strong primary and secondary markets and I was keen to secure wider exposure for them but found it difficult to break into the UK art fair circuit. So in keeping with the ‘do-it-yourself’ street art ethos, I decided to form my own fair focusing on street art and its related subcultures.

BM - Does the name Moniker refer to the use of pseudonyms by many street artists?

FS – Yes. I was working with friend and artist Felix Berube (AKA Labrona), a Canadian freight train painter who told me all about Moniker Culture and the Hobos of America. I registered ‘Moniker Projects’ as a domain name before I even thought of the fair I think.

BM - What sets Moniker apart from all the other art fairs that are so ubiquitous this time of year?

FS – We’ve established ourselves as London’s premiere event for contemporary art with its roots embedded in urban culture. This is what ties the fair together and we have firmly put East London back on the art fair map in doing so. We’re an unpretentious fair, accessible and unpretentious. You won’t find many obscure pictures on white walls with gallery assistants glaring at you at our fair. Every day is fun, we are known for generating a friendly unintimidating art buying atmosphere. It’s become one of the highlights of London’s Art Week for many people.

BM - You have decided to accept Bitcoins this year, why is this?

Nick Walker, Decibel No.1 . Art of Patron space curated and produced by Moniker Projects

FS – A mixture of reasons. I met several people from the Bitcoin community this year who really sold the benefits of the digital currency to me. Plus they were genuinely nice people who welcome social change. I wanted to know more about the decentralised system so decided to curate a 50ft Bitcoin inspired installation that will integrate artworks by Ben Eine, Schooney and Toonpunk. Bitcoin will be accepted as valid tender throughout the fair, not necessarily because we believe Bitcoin will our saviour(!), but exploring possible alternatives to the current financial system is a good thing.

BM - How do you select the Moniker-represented artists?

FS – Initially I like their art and then I like them. Sometimes it happens the other way around, I like the artist and begin to understand their work and their paintings may grow more and more on me.

BM - Which are the most exciting artists that we should look out for at this years fair?

FS – I’m looking forward to seeing work by SA artist Kilmany-Jo Liversage, Betz from Etam Cru, French Street artist Bom.k who debuts at the fair and Apolo Torres. Legendary Bristol stencil artist Nick Walker will be exhibiting his brand new ‘smoke series’ body of work in the Art of Patron space along side multidisciplinary artist Lauren Baker. The Renaissance is Now installation is going to be off the wall.

TIAF London

The Independent Art Fair London will be blowing us away again this year with 80 contemporary independent creatives from all over the world.

When? October 14th-18th

Where? Rag Factory, London

The Independent Art Fair London will be blowing us away again this year with 80 contemporary independent creatives from all over the world. Offering new talent as well as established artists the opportunity to showcase their work amongst others forms an inspiring environment full of photography, installation, video, painting, sculpture and every other way creativity can take form. The exhibition takes place in the heart of Brick Lane, in the eminent Rag Factory.

Slow – Co – Ruption by Dineo Seehee Bopape

An interview with the South African artist on her first UK solo exhibition at the Hayward’s Project Space, London.

Dineo Seshee Bopape is one of South Africa’s most admired, unconventional artist. Her first UK solo exhibition at the Hayward’s Project Space, Southbank, can best be termed as surprising, unexpected, puzzling or wonderful that your brain cannot comprehend it. Too many gadgets going on at the same time. It’s like you are not supposed to grasp what the display is about? Comprehending the works isn’t really the idea here I gathered. You walk into the space and you are challenged by a tremor of everything but the kitchen sink. From sculptural installation with video montages to constant flash photography, two TV set with no pictures flipping between analogue and digital visuals, a machine mix and re-mix ear-splitting sound. What is more? Timber, bricks, mirrors and plants, form multifaceted and wobbly configurations, often across the walls and on grass floor of the gallery, alongside a fresh sculpture conceived especially for Hayward Gallery Project Space. The presentation is overwhelmingly imposing.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from why do you call me when you know i can’t answer the phone, 2012

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 10 minutes 42 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

DSB: I was born in 1981 in Polokwane, South Africa. I was born on a Sunday. If I were Ghanaian, my name would be akosua/akos for short. During the same year of my birth, the name ‘internet’ is mentioned for the first time Princess Diana of Britain marries Charles; AIDS is identified/created/named; Salman Rushdie releases his book “Midnight’s Children” bob Marley dies ‐ more events of the year of my birth are perhaps too many to have accounted for... I did my undergraduate studies in Art at Durban University of technology, South Africa, (2004), and attained my MFA from Columbia University, USA, in 2010. I work generally in a variety of mediums, mostly installation and video and drawing. My work has generally dealt with issues/ideas of representation so to speak... and memory, whilst some resist the pressure of having to mean something.

Here and now, what made you want to take part in Africa Utopia festival and what do you hope to pull off?

DSB: I was invited to take part. And what I hope to attain is to brush up my talking skills, I get often nervous when I speak in public, and often unsatisfied after because there is so much stuff that remains unsaid. Perhaps agreeing to participate is a chance for another rehearsal for the next time.

How would you describe your art? Is it redemptive, ethical or relative and political. And when putting together your installations what is your end goal?

DSB: It depends on who the viewer is I guess. It can be redemptive. Whilst in the process of making a work, goal posts changes. There is a freedom of sorts that comes with not having a strict goal. The goal is an unamiable thing.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from is i am sky, 2013

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 17 minutes 48 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from is i am sky, 2013

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 17 minutes 48 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

Talk to us about your Africa Utopia exhibition at the London Hayward Gallery project Space?

DSB: "Slow-co-ruption" is the title of the show. I was thinking about data corruption, the data of narrative, of memory, of liberal socio-politics, self, language, sense and order and all thatcorruption implies… rupture... An interruption of a memory/a file/a story... about politics of space and the metaphysics of being... A death… ‘Productive’ death…The show has 3 main works and 2 supports, so to speak. In the first room is “Same Angle, same lighting”, a mechanical sculptural work which I made in 2010 but is now in its 3rd incarnation. The first version had a light that was shining repetitively, back and forth on to a dark photograph (just looking over and over again). The 2nd version which I had shown in Cape town at Stevenson had a camera that was supposed to capture the information on a photograph and send it to a nearby monitor, but the machine kept on failing and what stood in the monitor with it was a pre-recorded video (showing the movement that was supposed to happen); an external memory of sorts…

(Flabbergasting response or what?) Rendered speechless.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from is i am sky, 2013

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 17 minutes 48 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

And now in its 3rd reiteration in Slow-co-ruption, the camera sends information to several monitors/screens (hosts). The camera goes back and forth scanning the information off the paper (a scanned colour photocopy of picture of a lush garden from a garden and home magazine from the early 1990’s). This machine is hosted on and by these wooden supports and shop display things. Around “same angle, same lighting”- (the other supports) are several copies of video grass green/sky blue and also slow-co-ruption (stickers of flowers and eyes) the flowers are an almost random selection of native SA flowers and some from the garden image in same angle…. The eyes are those of an anonymous person and also those of philosophers Biko and Sobukwe who are also known for having written much about a need for rupture – both mental and spatial (so to speak). In the other rooms are the video “why do you call me when you know I can’t answer the phone” a piece from 2013 which is itself about the rupture of meaning or sense, a corruption or narrative. Whilst “Is I am sky” also speaks of a thing of absence, self-presence and of a kind of a metaphysical death to make a very insufficient summary…

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from Grass Green, 2008

SD digital video, sound

Duration: 6 minutes 52 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

Do you have a favourite piece from this exhibition and what next for DSB?

DSB: Not really, I love the different pieces differently...but currently I must say I am most excited about the "slow-co-ruption" stickers. On what next? I would like to show my work more on the African continent (abroad too), I would like to grow as an artist, to clarify my thoughts, for my work to be sharper, to continue being curious and continue to play... also to share with others... to remain healthy and able.

Africa Utopia 2015 art and ideas from Africa that are impacting the world

AFRICA UTOPIA was back for a third year – bigger and better. We interview designer SOBOYE.

Toumani Diabate, Baba Maal, Damon Albarn ,Tony Allen. Photo by Ade Omoloja

This year was one breath-taking summer for arts, music, dance and fashion festivals in London. What is more? The recently concluded third edition of the Africa Utopia Festival was one of the capital's forthright and most spectacular festival ever, celebrating all aspect of the creative arts industry.

Africa Utopia was a creative explosion of Jedi proportion that featured performance arts, music, dance, fashion, theatre, visual-techno art exhibition, family events and mouth-watering food market and much more besides. The whole shebang was spread out - in the streets, galleries, library, public buildings, and every available space and corner of London’s most vibrant cultural quarters – The Southbank Centre. This four-day fiesta enthused by the African continent and Diaspora delved into the dynamic and ever-changing contribution of modern Africa to art, culture and ultimately to our society. Organisers hope the festival will also help make connections between artists and activists, get more accessible; to engage.

Discussions and debates deliberated on sustainability vs profit, digital journalism and digital activism, youth education and power to African feminism. Furthermore, in a nod to the present refugee crisis, the migration debate asked the question: “Why do people flee? What awaits them where, and if they reach their destination?” It’s a question for us all to ponder on at this time. The Talks/Debates consisted of defining speakers including the traditional suspect, journalist, author and arts programmer Ethiopian-born Hannah Pool, who must be noted has been involved in Africa Utopia from the very start. Next in line is singer-song-writer and UN Ambassador for HIV/AIDS Malian, Baaba Maal, who also has been involved with AU from its birth. As well as Jude Kelly CBE, Artistic Director, Southbank Centre. The lot are experts in contemporary art, art history, music and green politics, each addressing the historical relevance of arts and culture - including the power of art in activism and the role of women and young people who have made a huge contribution to our arts as part of our lives and still motivates us all in creating future change. These themes are conceived to appeal to taste, of all ages, colour, cultural aficionados and newcomers alike.

Chineke Junior Orchestra with founder Chi Chi Nwanoku and conductor Wayne Marshall. Photo by Ade Omoloja

Even more so, the tune line-up was a must-hear for anyone and everyone fascinated by great live performing. First on stage was Malian singer Kassé Mady Diabaté of royal stock and acknowledged as one of West Africa's finest singers. He was accompanied by fellow Malians: Ballaké Sissoko, a noted player of the kora; Lansiné Kouyaté performing on Kora & Balafon (The balafon, also known as balafo is a wooden xylophone - percussion idiophone from West Africa) and Makan Tounkara, a gifted composer, arranger, singer, and n'goni artiste. (The n’goni, an ancient traditional lute found throughout West Africa). To bring the festival to a close was the master of it all - Nigeria’s Tony Allen with friends. And oh boy were they great!

Tony, is a skilful drummer, composer and songwriter and once musical director of late Fela Anikulapo Kuti's band Africa 70 from 1968 to 1979. Furthermore, he’s famed as the powerhouse behind the late Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat movement. It’s recognised that Fela said: “without Tony Allen, there would be no Afrobeat music”. In alliance with Tony on stage; Baaba Maal, multi award-winning singer/song writer and Toumani Diabaté, a Malian kora player, genius of African music and widely recognised as the greatest living kora player. And in a rare father-and-son kora-playing collaboration, Toumani Diabaté and his son Sidiki Diabaté put down a spell-binding presentation. It was a mind-blowing ensemble. A-ma-zing! And to put the last bit on the Tony Allen and friend’s fusion was French star rapper Oxmo Puccino (born Abdoulaye Diarra) a hip hop musician born in Mali. The whole shebang brought the house down. It was a high octane musical extravaganza of fantastic proportion that received a rapturous reception at every song and every notes that rings out. These musicians nailed and killed it in equal measures. There was an eight minute standing ovation. For a man who turned 75 in August, Tony Oladipo Allen, is remarkably springily. He still hits the studio (and treadmill, I suppose) every day. He is just as you’d imagine, small, frail and thin looking, dressed in a classic white African traditional classic number with bold abstract designs and he outdone it with a white Fedora Hat. Maybe this is what comes from churning out some five gigs a year for over 50 years. He has delivered some of the music most indelible music albums and concerts from Africa to Europe and North America to Australia and the Americas – straight-up.

Toumani and Sidiki Diabate, Baba Maal. Photo by Ade Omoloja

With all the serious shows and presentations that took place, however, the three that stood-out for the festival – in my modest view - are the music performances and fashion presentation curated by Samson Saboye, of Nigerian parentage, from Shoreditch-London. Soboye brings together a team of leading designers from Africa and the African Diaspora to present an inspirational and exciting women’s wear, menswear and accessories.

“I’ve been a Fashion Stylist for many years now with a spell designing and manufacturing soft furnishings, which led me to open SOBOYE.

Africa Utopia is a great showcase to celebrate the importance and significance African Culture to the rest of the World. London has the highest population of African nationals from all over the continent and the contribution that Africans have made to the city is noteworthy. Our presentation is called DIASPORA CALLING! A presentation of African Contemporary style, inspired by Street Style photography. Our show producer Agnes Cazin from Haiti 73 Agency conceived the concept as we were searching of different ways to present fashion that was away from a traditional catwalk show. We are showing the diversity of Africa that will linger on even after the festival: the Joy, the vibrancy and richness of its people, who mostly have an innate sense of style that is not dictated by the latest trends or Designer head-to-looks. The Modern Style-conscious African’s style is a mash-up of pop culture, vintage clothes, self-made fashion and images fed daily through Instagram and Pinterest, of which they are fully engaged in. All these influences are absorbed in to the visual memory banks and stored for future referencing at any time. This then in turn manifests itself in the Individualist looks that we see influencing mainstream Western style today”.

On the small matter of who SOBOYE designs for: “SOBOYE designs are for the fashion savvy, confident, style literate person, with their fingers on the pulse and a zest for life. The Women’s wear came a year after the Men’s collection and is designed in collaboration with Designer and friend Chi Chi Chinakwe”. (A moniker moment in this festival is the premiere of Chineke, the UK’s first professional classical orchestra made up entirely of musicians of African descent and minority ethnic classical artists performed a tribute to the black teenager Steven Lawrence that was murdered in a raciest attack in 1995) Soboye expressed: “Our customers tend be in the creative industries and have an eye for well fitting, original clothes with an attention to detail. Our clothes add to the enjoyment of dressing up and I’ve yet to see someone wear any of our pieces and not look and feel better for wearing them… Sidney Poitier is my all-time style icon. Not only was he well-dressed, he always carried himself with such dignity and broke so many barriers by being such an accomplished actor. Currently Pharrell Williams and Solange Knowles would both be great brand ambassadors for SOBOYE." So if they are both reading this come on in… we are waiting for you. Yes, of course they read roomsmagazine.com.

Beside ambitious philosophy in the horizon: What does the future hold for Samson Soboye? “We plan to expand our online business and build the brand. We’d like to secure good investment to consolidate the business and allow for expansion and growth and for that to be manageable. We’d like to be the ‘go-to’ brand for the talented, ambitious discerning globe trotter “.

Ten Designers in the West Wing

London Design Festival presents ‘Ten Designers in the West Wing’, the work of an impressive list of renown designers, exhibiting in collaboration with their best clients.

Alphabeta, Luca Nichetto for Hem

Located in the Somerset House, the festival has selected ten major designers from various fields to showcase their design stories in a contemporary and innovative way. Reserving the newly renovated rooms at the west wing of the building, the designers get full freedom to make their story as complete and convincing as possible.

As for the English Drawing Room, designer Faye Toogood will be handling renovations herself. Creating the illusion of an abandoned country house, she uses charcoal and translucent plastic sheets to enhance space between four walls, reinforcing the idea of walking through a whole house.

Covering film and set design, award-winning designer Tino Schaedler joins forces with virtual reality director Nabil of United Realities, sending us on a trip to space by fusing vanguard technology aspects of storytelling.

For the keen book lovers amongst you, British designers Edward and Jay Osgerby will lure you into their intimate Reading Room where their furniture will be showcased, alongside their new book ‘One By One’.

Tabanlioglu Architects & Arik Levy Render

Faye Toogood

Optimist Design & United Realities

Many of the rooms will be interactive, transforming design into a creative experience. Industrial designer Arik Levy takes this a step further by not only creating interaction between the viewer and the room but also between art and architecture. Collaborating with architect duo Tabanlioglu, the artwork will let you explore the theme of transparency.

Other talent attending the exhibition will be Alex Rasmussen, Luca Nichetto, Jasper Morrison, Nendo, Patternity and Ross Lovegrove.

Mon-Wed & Sun 10am-6pm, Thu-Sat 10am-9pm

FREE

@L_D_F

Artists and Scientists at Music Tech Fest

The exciting formula for championing future creative and technological collaboration in music. We interview Andrew Dubber, Music Tech Fest's Director.

Soft Revolvers by Myriam Bleau

Andrew Dubber, Music Tech Fest’s director, explains to me the freedom Music Tech Fest fosters in joining creative musicians and technological minds in an all-inclusive environment – the aim is to ultimately liberate the music technology scene and revel in the mayhem that ensues.

How and why was 'Music Tech Fest' conceived and what developments has it gone through to make it the internationally-reaching community it is today?

I wasn’t there for the first Music Tech Fest. It was something that came out of the European Road Map for the Future of Music Information Research. Michela Magas was the scientific director for that project - and was the founder of the Music Tech Fest. The idea was to bring together artists and scientists, academics and industry in a ‘hands on’ experimental environment - rather than just a conference. I came along to the second one and, like most people who now work for MTF - I basically just never went home. I was asked to take on the role of director of the festival, and we have had invitations - sometimes through some of my own professional connections - to bring the event to different cities. It’s different everywhere we do it, and we learn a lot by doing each one. But what makes it work is the fact that it brings together such a diverse range of brilliant and interesting people. It’s not a matter of controlling the outcome. You put them together in a room and watch what happens.

Why do you think it is important for musicians working with technology to meet face to face in a world saturated by online ‘music technology’ content?

I don’t think it’s necessarily important for musicians to meet each other face to face. It’s nice, just as any personal human interaction is nice. But there’s a lot that can be done through online collaboration between people who have the same language and mode of working. What’s important is that they meet *other types of people* with different skills and frames of thinking. People who aren’t musicians, but bring something else to music. And to make that work, people need to build something together. If you want to innovate in music, you need creative technologists, designers, hackers, musicians, artists, product designers, music industry people - a whole range of different minds. That’s what the face to face stuff is for. You get people working collaboratively and it opens up all sorts of unimagined possibilities.

‘Music Tech Fest’ seems different in that you pride yourself on being ‘a community with a festival, not a festival with a community’ - why is it important to 'bring down' the hierarchy that a lot of creative ‘festivals’ have and somewhat ‘level the playing-field’ for musicians working with technology?

There are a few important things here. First - we want to remove barriers to participation. Anyone who wants to play music, make technologies, hack, research or find out about music technologies should not be prevented from doing so because of financial restrictions. Second, it’s important to us that things that happen at Music Tech Fest have a life beyond the festival. New projects begin, new businesses are formed, new art installations are imagined, new performances planned - that sort of thing. That’s what Music Tech Fest is for. It’s a catalyst for the community. Where people come together, get exposed to new concepts and experiences, meet new people, have interesting discussions, make new prototypes and so on - but then go off to develop those further and maybe come back and showcase those things on the main stage at a later Music Tech Fest.

A lot of the creative developments in the ‘music tech’ world aren’t solely to do with music anymore - how and why is cross-collaboration in artistic mediums important and how does ‘Music Tech Fest’ foster these concepts?

The edges where music stops and other stuff starts has always been blurred - but now more than ever. We’re interested in music for its own sake, because music is amazing - and we’re also interested in music as a tool for other things (social change, industrial innovation, education…). Music is something pretty much everyone has a relationship with in one way or another. It’s the bit that connects the tech-heads with the artistic people, the academics with the industry. We’re working with Volvo trucks and Philips lighting. Those organisations might not be thought of as music related, but they see the value of a transversal approach to innovation, and music as a galvanising force that gets young people interested in technology and engineering. The cross-collaboration in the arts is especially important in an age of computing because the artificial barriers between storytelling, music, film, visual arts - even taste and touch - are broken down in our increasingly synaesthetic and multi-modal world.

The improvements and accessibility of technology in general is something that is obviously allowing more people to engage with it. How has the festival engaged with the issues of inaccessibility to technology to allow a wider engagement with music tech?

It’s a really important strand of what we do. For instance, we’re working closely with a number of organisations who are focused on using technology to remove barriers to participation for people with disabilities. We encourage our hackers to keep accessibility in mind when developing any new projects and we showcase projects that are about making music available to more people in more places - for instance, the One Handed Musical Instrument (OHMI) Trust, Drake Music and Human Instruments. It’s also a key part of our #MTFResearch network principles. The Manifesto for the Future of Music Technology Research, which came about as a response to the Music Tech Fest we held at Microsoft Research in Boston. See: http://musictechifesto.org

All images courtesy of Andrew Dubber

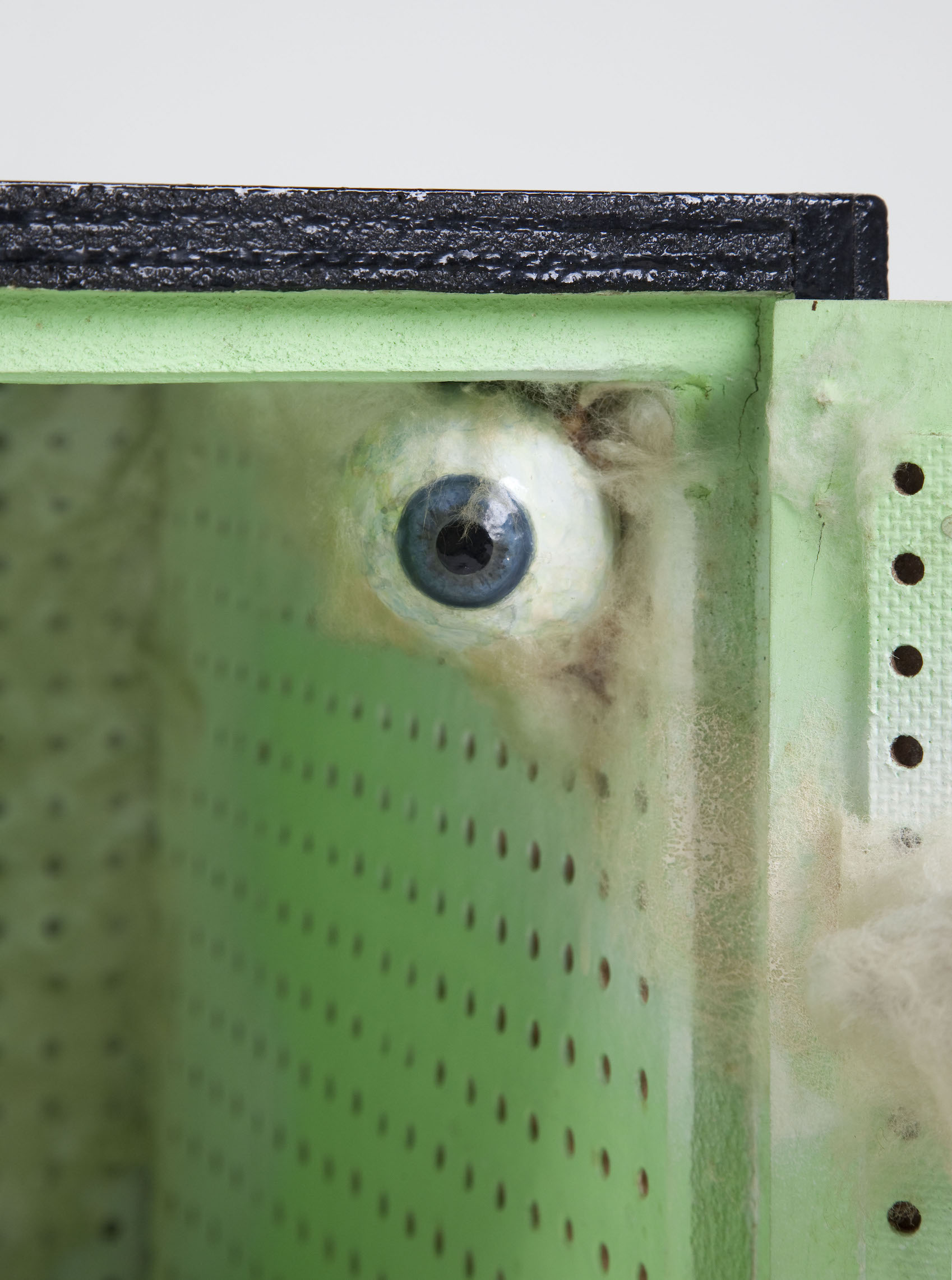

Tetsumi Kudo at Hauser & Wirth London

A seminal figure in Tokyo’s Anti-Art movement in the late 1950’s, multidisciplinary artist Tetsumi Kudo (1935 – 1990) left behind a lasting legacy: this autumn, Hauser & Wirth London will host an exhibition of his works, marking 25 years since his passing.

A seminal figure in Tokyo’s Anti-Art movement in the late 1950’s, multidisciplinary artist Tetsumi Kudo (1935 – 1990) left behind a lasting legacy: this autumn, Hauser & Wirth London will host an exhibition of his works, marking 25 years since his passing.

The exhibition will present a selection of work dating from the first ten years that Kudo spent in Paris (1963 – 1972), following the completion of his studies at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts in 1958.

Although marginalised in North America and Europe for many years, Kudo’s influence on subsequent generations of artists has been profound and far-reaching. The artist spent the majority of his career preoccupied with the impact of nuclear catastrophe and the excess of consumer society associated with the post-war economic boom, his interest in these topics intensified upon his exposure to the European intellectual scene.

Developed in the context of post-war Japan and France, Kudo’s practice, which encompasses sculpture, installation and performance-based work, is dominated by a sense of disillusionment with the modern world – its blind faith in progress, technological advancement, and humanist ideals.

Consisting of a die enlarged to over 3.5 square metres with a small circular door allowing the viewer to climb into the dark interior lit with UV light, ‘Garden of the Metamorphosis in the Space Capsule’ will form the exhibition’s focal point, shown alongside examples from his cube and dome series.

In his cube series, small boxes contain decaying cocoons and shells revealing half-living forms – often replica limbs, detached phalli or papier-mâché organs – that merge with man-made items. These sculptures were intended as a comment on the individualistic outlook and eager adoption of mass-production which he found to be prevalent in Europe.

Kudo’s dome works appear as futuristic terrariums: perspex spheres fed by circuit boards or batteries house artificial plant life, soil, and radioactive detritus. What is being cultivated in these mini eco-systems is a grotesque, decomposing fusion of the biological and mechanical, illustrating Kudo’s feeling that with the pollution of nature comes the decomposition of humanity.

The simultaneously political, yet highly aesthetic, characteristic of his sculptural work is at the centre of the contemporary oeuvre.

Tetsumi Kudo

Hauser & Wirth London, North Gallery

22 September – 21 November 2015

Opening: Monday 21 September, 6 – 8 pm

Ai Weiwei – Creating Under Imminent Threat

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is as well known for his art as for his activism. A steadfast critic of the Chinese government, Ai has been denied a passport for over four years and has been unable to leave or exhibit work in his native country.

Photograph by Harry Pearce Pentagram 2015

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is as well known for his art as for his activism.

A steadfast critic of the Chinese government, Ai has been denied a passport for over four years and has been unable to leave or exhibit work in his native country.

Recently Weiwei posted a photograph online of him holding up his newly returned passport and announced that he has also been granted an extended six-month visa to visit the UK, which he will coordinate with his Royal Academy retrospective.

On the 19th of September 2015, The Royal Academy will host the first major retrospective of his work, showing works from his entire oeuvre. From the smashing of a Han Dynasty vase (which will appear in the show), to the poignant critique of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that killed over 5,000 Chinese children, Weiwei’s work is bold, controversial and unforgiving.

All the works in this show have all been created since 1993, the date when Weiwei returned to his native China from America. This exhibition will show works that have never before been seen in this country, and many have been created specifically for this venue, Weiwei navigating the space digitally from China.

Often labeled as an activist or a political artist, this social conscience is what has influenced most of his works to date. Living under constant imminent threat from those with absolute authority, Weiwei’s work is created out of adversity and struggle. His oppressors are ones who are able to work above and therefore outside the law, and for that reason his struggle is a very real one. Despite this, Weiwei will not be defeated, and continues to critique the government and its actions towards the Citizens of his beloved China.

In a career spanning over three decades, his hand has also been turned to: activism, architecture, publishing, and curation, in a tour de force of creative activity. The artist worked alongside Herzog & de Meuron (the same company to design the Tate Modern in 1995) to design the 2008 Beijing National Olympic Stadium (commonly known as the Birdsnest). This project was born from a building Ai designed nine years before, when he needed a new studio, and decided to simply build it himself.

This confident disregard for convention is the attitude with which he approaches all of his work, and it has gained him many critics. The most notable of which being the Chinese government themselves, who have arrested him, seized his assets, terrified his wife and child, tracked him daily, tapped his phones, and rescinded his passport.

Perhaps most well known for his Sunflower Seeds artwork, in which he filled Tate Modern's Turbine Hall with 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds. Each seed was hand crafted and painted by hundreds of Chinese citizens from the city of Jingdezhen, in a process that took many years. Visitors to the show were overwhelmed to see the vast expanse of seeds, and were originally invited to walk and sit upon them, interacting with the work in a way in which we are rarely allowed to. (For safety reasons this was later disallowed)

The sunflower seeds appeared uniform but upon close inspection revealed themselves to be minutely unique, created using centuries-old techniques that have been passed down through generations.

In the Chinese culture sunflowers are extremely important, Chairman Mao would use the symbology of the sunflower to depict his leadership, himself being the sun, whilst those loyal to his cause were the sunflowers. In Weiwei’s opinion, sunflowers supported the whole revolution, both spiritually and materially. In this artwork, Weiwei supported an entire village for years, as well as creating something that promotes an interesting dialogue about the very culture that created it.

Weiwei’s work is about people, about the often nameless many who are oppressed or ignored. It is about justice for those who have been abandoned or neglected by those who are there to protect them, and it is most primarily about their basic human rights.

It is tragically ironic that those human rights that he has worked so tirelessly to protect for others are those denied him by his own government.

The Royal Academy has turned to Crowdfunding to help raise £100,000 to bring the centerpiece of the exhibition to Britain. Weiwei’s reconstituted Trees will sit in the exterior courtyard and be free to view for all. The campaign has just over a week left and still needs to raise just over 25% of its target.

Get involved here

The show will be on between

September 19th – December 13th 2015

Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BD

All images courtesy of Royal Academy

Mark Mcclure | Neatly Ordered Abstraction

Mark Mcclure is an artist who utilizes reclaimed wood to create precise geometric artworks. Check out the interview by Benjamin Murphy

Mark Mcclure is an artist who utilizes reclaimed wood to create precise geometric artworks. Using both painted and untreated woods; his works have a crisp yet raw feel that exist symbiotically to create an ordered and balanced work. Sitting somewhere between sculpture, collage, and painting, his work is best interpreted when viewed in its relation to Constructivism.

BM – You combine both old and new materials in your work. Does the history of the materials ever dictate the aesthetic of the piece?

Not really. I tend not to do things that way round. I choose the materials for their colour & texture - in the same way a painter might choose from a selection of paints or charcoals. Texture, colour, and any remnants of past use - all contribute to a pretty broad palette. If I’m after specific textures or remnants to use - then I might stain the wood to adjust the colours slightly - but the history of materials never really takes priority.

BM – There is a conflict between form and functionality, which do you think takes precedent?

It’s interesting that you’ve preloaded the question suggesting that form and function are independent of each other. To me it’s all a sliding scale depending upon the context of a piece.

If I’m creating a wooden mural then it would automatically adopt the function of a wall surface - whilst also being an artwork. If I put a hinged door in a sculpture - it becomes a cupboard of sorts. It might be a bloody expensive & abstract cupboard - but it’s still got the potential to be a cupboard. It’s down to the context of the artwork - who owns it, how they perceive it, probably how much they paid for it as well.

BM – You have mentioned to me before that you would identify yourself as a constructivist. The Constructivists believed that the true goal was to make mass-produced objects. Your work is very hands-on, how would you feel about others making it for you?

The Constructivists had their own in-fights over the ideas of mass production. The likes of Rodchenko straddled the worlds of art & design - whilst others such as Naum Gabo believed in a purer approach that didn’t cross over into function. For me that goes back to the sliding scale & context of the artwork.

But mass production is a different beast to having other people involved in making artworks. The Uphoarding wall I created at the Olympic Park last year involved up to about 10 different people over a 10 month period - and in the future I’ll make artworks in materials I will never have time to master myself - concrete, metal etc. - So it’s inevitable that others will end up producing some of my work.

BM – Would it still feel like your artworks if you didn’t get your hands dirty?

Yes - but without the emotional attachment that comes from being so involved at every step - an attachment that probably stems from the craft side of things. They’d be put on a different shelf in my mind - but they’d still be mine.

BM – What makes the Constructivists artists as opposed to craftsmen?

Many of them were craftsmen - in that they strived to be masters of their materials - producing clothing, design objects etc. with a view to targeting a consumer market. Others had less tangible, idealistic aims - challenging or celebrating aspects of the world they lived in - expressing feeling and emotion etc. and I guess that’s what makes them artists.

BM – The Constructivists’s aim was to make artworks that force the viewer to become an ‘active viewer’, how interactive is your work and do you intend for it to be touched?

Interaction is really important and working in such tactile materials has meant that it’s hard not to touch a lot of my work - which is totally cool. I love the idea of artworks in galleries being more playful and interactive - though interaction doesn’t always have to involve touch. This is something I’m going to play with more this year…. some exciting ideas on the cards.

BM – When you clad the floor or a wall, do you see this as a two-dimensional or a three dimensional piece?

2 dimensions. I’m not too sure where the tipping point is - probably somewhere around 4 inches thick.

BM – Is collage then 2D or 3D? Would you say your work is a type of collage?

Potentially both - can we invent dimensional fractions here & now? 2.3 dimensions? I wouldn’t say my work right now is collage… though it has been. Collage to me is more layer upon layer than piece by piece - and involves a lot more glue.

BM – What exciting future projects are you working on?

A nice mix right now - a large bespoke floor and a few other fun pieces towards the ‘function’ end of that sliding scale we mentioned earlier - and also some new artworks for exhibitions & fairs over the summer. I’m also exploring some materials to add a new aspect to my work later this year. Some busy & exciting months ahead.

More of Mark’s work can be seen online at www.markmcclure.co.uk

Charles Avery alternative reality at Edinburgh Art Festival 2015

This year's Edinburgh Art Festival brings the immersive and complex conceptual world created by Charles Avery to engulf us.

This year's Edinburgh Art Festival brings the immersive and complex conceptual world created by Charles Avery to engulf us.

Edinburgh’s annual arts festival sets off 30th July, combining contemporary art exhibitions as well as those of more historic movements. Working with leading art spaces throughout the UK, the festival is a month long happening bringing us exhibitions, events and talks from a wide range of great artists including Charles Avery.

Represented by Ingleby Gallery, Avery is presenting more detailed insight into his imagined island with The People and Things of Onomatopoeia. Beginning in 2004, The Islanders series has continued to present the intricate details of his imagined land, evolving to give the audience understanding of the complexities of the inhabitants’ personalities, the nuances, habits and dislikes of groups and individuals.

Avery’s work has an element of fantasy but is not simply a flat rerun of the genre; there are many aspects of this world that mirror issues in our own society as well as introducing abstract concepts of myths and rumors as a potential reality in this universe, even if only existing as a belief by the inhabitants.

The audience experiences this through a wide multimedia approach to a kind of open-ended storytelling using a narrative text, visual imagery, sculpture and installation on a large scale, often presenting objects used by constituents or posters from the streets of Onomatopoeia. These are used as tools for the audience to interpret and contextualise this world.

To add to the incomplete or continual nature of the work, many of Avery’s sketches are unfinished, giving the feeling that the work continues to live alongside the artist. The inhabitants’ lives do not begin and end during the course of the exhibition, there is an endless scope of story to be told about this place and these people.

It is compelling to think of this fictional world as a form of escapism for both the artist and the audience, however, the complexities it inherits being no less problematic than those of our own society can be somewhat grounding, not allowing us to submit to a utopian fantasy.

In addition to this Avery is also presenting a tree from Onomatopoeia cast in bronze at Edinburgh train station as part of the festival which runs until 30th August 2015.

Marc Quinn – The Toxic Sublime

White Cube Bermondsey

15 July 2015 – 13 September 2015

British-born artist Marc Quinn is perhaps most well known for his 1991 artwork Self: a life size sculpture of his head, using 4.5 litres of his own blood. Bought by Charles Saatchi for £13,000 in the year of its conception, this work has accrued almost mythical status.

In 2005, Quinn took over the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square with his sculptural artwork Alison Lapper. Alison, who is an artist herself, was born without arms and with incredibly shortened legs. This work showed her nude and unflinching, proud of her nakedness. Deformities such Alison’s are naturally compelling to observe due to their uniqueness. As a species we are intrigued by anything unusual or different, but society tells us we mustn’t. Looking upon such a drastic disability is often thought to be an insult to the recipient, and children quickly learn not to stare.

Quinn's sculpture rejects these social conventions and shows her in all her unique beauty. Placing her on a plinth he shows us that is ok to look (in fact he forced us to do so), and that Alison has nothing to hide. There was no shame in her face. This work was bold, brazen, and brilliant.

On the 14th of July Quinn’s new show The Toxic Sublime opened at the White Cube gallery in Bermondsey. This new body of work is quite far removed from his bodily excretions and his sculptures of those without limbs, seemingly more reserved and delicate.

Most prominent and striking in this show are his stainless steel Wave and Shell sculptures, dotted around on the gallery floor. Highly polished in some areas they are more Cloudgate than Wave, but are beautiful nonetheless.

The other and more subtle works in the show are vast undulating canvasses, affixed to bent aluminum sheets. Upon these canvasses is a mixture of: photographs of sunsets, spray paint, and tape (amongst a myriad of other less determinable shapes). The canvasses once painted are abrasively rubbed against drain covers in the street.

The inclusions of these humble drain covers into the artwork is possibly the most interesting element to the whole show. Something described in the press release as being:

“.. suggestive of how water, which is free and boundless in the ocean, is tamed, controlled and directed by the manmade network of conduits running beneath the surface of the city.”

Quinn’s notoriety was gained in the early nineties for bravely showing the public that which we usually hide: faeces, blood, semen, and the like. Gilded and placed on a plinth for all to see. His earlier work depicted that which lies beneath, where as this show obscures exactly that. The drain cover is an object that hides these very secretions, burying them underground.

Quinn's work is brilliant at showing us the beauty in the overlooked and the grotesque, and this show to some extent does just that. The Toxic Sublime is definitely very beautiful, but it lacks a certain grotesqueness that is a Marc Quinn trademark.

Photographs from Marcquinn.com

White Cube Bermondsey

15 July 2015 – 13 September 2015

Guillermo Mora – not your usual acrylic painter

“It would be amazing to see all the paintings of the world separated from their canvases and falling on the ground.”

Spanish artist Guillermo Mora is coming to a London gallery near you. I recently interviewed the man and he proved to me why he’s worth your time.

What is it that you enjoy the most about working with layers and layers of acrylic paint? And also what you enjoy the least about it?

Layers in life, layers in painting. Painting is not far from the way everything is constructed. We are made of layers as well. I like to conceive painting as a body, as something not eternal but alive, clumsy, tired, and capable of losing its entire shape or parts of it. Flaubert used to say: “as soon as we come to this world, pieces of us begin to fall”. I feel this exact way on painting. It would be amazing to see all the paintings of the world separated from their canvases and falling on the ground.

On the other hand, it’s weird for me to say something that I dislike about painting, but I could say its autonomy. Even though you think you can control all its processes, it always cheats you. There’s always something unexpected. Life is unexpected and painting is too.

What’s your creative process like?

“Add, subtract, multiply and divide” is my statement (and the presentation of my website). I think these words not only belong to mathematics but also to our everyday acts, thoughts and behaviors. Painting is a complex body in the world in which all these actions can take place too.

How did you feel when you won the Audemars Piguet award?

First of all, surprised. I was competing with very well known international artists and I never expected I could be the one that got it. Then I said to myself: “Guillermo, from now on you have to work much harder.” When you win an international award, it puts you immediately in a new position. I realized how less important the economical aspect of my work is. It’s true that money helps, but the most important thing was that a lot of people started to pay attention to my stuff. From the moment you win a prize, you have to demonstrate why you won it.

You have an upcoming group exhibition entitled Saturation II – Add Subtract Divide. And you’ve also described defined your work by including multiplying. In what way do you feel that your work accomplishes these operations?

Adding has always been linked to the idea of painting but we have to think that when we add something we subtract possibilities to it too. Then if I want to add, I have to divide the material into pieces, and this action is also a way of multiplying. These four actions are not as different as we think and can be easily included in my everyday process. They help me to uphold the idea of a constant changing painting.

If not Spain, where else would you like to permanently set up a studio and why?

United Kingdom for its contradictions and irreverences. Things happen when controversy is constantly present.

Kate Clements: The bride stripped bare by her bachelors

What makes Kate Clements a truly great artist is the conversation that her work evokes about the female gender and issues of narcissistic female adornment.

To the uninitiated viewer, looking at Kate Clements’ intricate glasswork, it might be easy to dismiss her as simply another talented decorative artist.

Whilst there is no doubt that she is extremely talented at the physical manipulation of kiln-fired glass, what does really make Clements’ work stand out? What makes her a truly great artist is the conversation that her work evokes about the female gender and issues of narcissistic female adornment. Clements’ work goes far beyond obvious feminist debates about woman as object and the power of the female form. Instead, what Clements seeks to uncover is the very psychological reasoning that leads to the cultural construction of feminine identity, and how women’s efforts at fulfilling such ideals can lead simultaneously to feelings of guilt and individual power. Adding to this is her performance work, which examines the ideas of purity and power, using metaphors presented by external objects as a means of examining metaphysical notions of being.

Constructing decorative, non-functional glass headdresses which function as a separation between viewer and ‘wearer’, Clements highlights a persistent desire by women to transcend their physical nature, in the hopes of achieving the socially constructed fantasy of a ‘perfect’ woman. Using such an elaborate and fragile medium adds to the sense of counterfeit perfection suggested by the focus on veils and crowns, key motifs of the beauty queen and the bride. It is this close examination into our cultural constructs and farcical use of adornments that transform Clements’ work into something more than pure decoration, adding layers of meaning that make us examine the very society we live in.

Hi Kate, can you tell us a bit about yourself as an artist? What are your passions? What questions still need answering for you?

I work primarily with glass but I describe my work as sculpture and installation. I have just completed my masters at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. Over the past two years I have explored the ambiguity of fashion—its capacity for imitation and distinction; its juxtaposition of the artificial and the natural; its ability to divide people by keeping some groups together while separating others and accentuating class division. I’ve come to understand the lifecycle of fashion as a process of creative destruction where the “new” replaces the “old,” yet nothing is truly new.

I am still exploring this and find inspiration in the perspective of critical theorist Georg Simmel whose observations over a hundred years ago remain all too relevant in today’s Gilded Age. “Fashion elevates even the unimportant individual by making them the representative of a totality, the embodiment of a joint spirit. It is particularly characteristic of fashion - because by its very essence it can be a norm, which is never satisfied by everyone...” Style, as Simmel suggests, both unburdens and conceals the personal, whether in behavior or home furnishings, toning down the personal to “a generality and its law.” My choice of materials comments on society’s need to conform and maintain distance.

Let’s talk about your chosen medium. What are the benefits and difficulties in working with glass? How did you first discover your interest in kiln-fired glass?

When I was 17 I took a pre-college course in kiln-fired glass at the Kansas City Art Institute, which was primarily mosaic and plate making. The professor saw potential in me and when I started my bachelors there in the fall I trained as his tech and teaching assistant for the course. I continued that job for my four years in undergrad. Because it was only offered as an elective, I learned the fundamentals through instruction but was substantially self-taught.

Working in glass has pros and cons. The glass community is small and very supportive of its artists. Because of the nature of the material, when you are working with it hot you usually need the help of one to four people to make a piece - so the sense of community is very strong.

A con can be the constant struggle of defending the material. The question of why someone creates paintings is asked much less than why someone works with glass. However, the constant question of ‘why glass’ pushes glass artists to address the relevancy of the material in the conceptual nature of the piece as well a technical one. Working within a craft material there is a wide spectrum of what people choose to do with it. It can range from pipes and paperweights to fine art. If I am speaking to someone outside of the glass world and they ask me what I do and I say glass they normally follow up with asking if I can make a pipe for them.

Breaking outside of the glass community can be difficult too. I would love to be showing in galleries that didn’t only represent other glass artists. Not to get away from other glass artists but so viewers could understand working with glass as fine art and not glass art. This seems to be a line that can be difficult to cross.

What relationships to the female form does your work provoke, and how important is it for you to express these concerns in your work?

I think initially my work was heavily reliant on the female form. As a young woman, I felt the pressures of conforming to some sort of social construct of beauty. At times that has made me feel guilty because I felt a sort of pleasure and power in partaking in that construct.

In recent work I have been addressing how these constructs get translated in different stages of the adaptation of ‘fashions.’ How taste, even ‘bad taste’ can be celebrated in aristocratic society, but once mimicked by a different social sphere it can become kitsch and regarded as ‘aesthetic slumming.’ The concept of fashion and its association with modernity is interplay between individual imitation and differentiation. Fashion, adornment, and ornament all have vicious life cycles; newness is simultaneously associated with demise and death. Though fashion and adornment are closely related to the body, ornament can expand to architecture and environment.

I really love your performance work which I find evocative of the work of Matthew Barney and his use of the body as a vessel for exploring ideas of the human condition. In your piece, Cleaning, the situation transcends the realm of normality and speaks of a higher plane of fantastical reality where juxtaposed items like smashed glass and sweet milk come together to form metaphors about us as human beings, speaking particularly of the paradigms that surround women as having to be ‘pure’ and ‘clean’, expressed powerfully in the denouement of the piece. Tell us a bit about your thoughts behind this and what you wanted to achieve.

This was a very early piece for me that was dealing with my personal experience as a victim of date rape. This marked a turning point for me that was also inspired by a speech by Eve Ensler where she describes the verb prescribed to girls as ‘to please.’ I felt strongly that for a long time I had allowed that verb to describe my interactions with men. There is a rawness and vulnerability in this performance that is mixed with anger.

Who and what influences your work? Are there any artists you recognise as having a big impact on you and your working style?

I just adore Jim Hodges’ work. I think the wide variety of materials and mediums and the way he handles them is truly inspiring and something I look to if I am nervous about working with a new material. Matthew Barney and Alexander McQueen were huge influences in the glass headdresses and the idea of masquerade and costuming. Other influences have been the palace architecture of Catherine’s Palace in Russia. I love the over-the-topness of the patterning and the idea of excess in a space that blurs the boundaries of public and private, the domestic, and the idea of display.

You have stated that your glass headdress designs function as ‘a separation between viewer and wearer’ but that this distance is only a ‘counterfeit perfection’. How important is it for you to address ideas of distortion and fantasy in your work?

I enjoy working with things that are recognizable, but nonsensical and fantastical in their execution. I am interested in the perceptions we have in what we think we are displaying, what we actually are displaying, and how we display it. Some materials can transcend their own materiality. The glass can be seen as ice, plastic, or sugar in the headdresses. In newer work it reads as growths or caviar. Regardless of what it appears to be the fact remains that it is extremely fragile and futile. In a newer piece there is a vinyl treated chintz sofa covered in glass beads. The shiny plastic is reminiscent of plastic covered sofas as a means to preserve something nice, but it can also read almost like a piece of porcelain because of the patterning of the fabric.

What is your definition of ‘creativity’? What does it mean to be ‘creative’ in today’s world?

I believe that creativity is driven by never being satisfied with what you’ve accomplished. That there is always something that can be pushed or questioned within a material or challenged conceptually and that ending up somewhere completely different from what you intended is usually a good sign.

If you could go back in time, what advice would you give to yourself ten years ago? What have you learnt as an artist that was unexpected and what advice would you give to others?

The advice I would give myself is to never doubt your interests no matter if conceptually they might sound simplistic. There is usually something there that can be unfolded into something fairly complex.

Not being intimidated by not being technically trained in a material. Coming from an outside perspective and not knowing the right way to use a material takes away restrictions or inhibitions that might have been taught and allows a certain amount of freedom.

Interview with artist and filmmaker Anna Franceschini

For Anna Franceschini, film is more than just a medium. It’s a living, breathing form in itself – it’s modernity manifested behind a silver screen.

For Anna Franceschini, film is more than just a medium. It’s a living, breathing form in itself – it’s modernity manifested behind a silver screen.

Milan born and bred ‘documenter of the soul’ Anna Franceschini boasts an impressive résumé of exhibitions, awards, fellowships and residencies across the world on her belt. With her numerous accolades one must wonder that she’s certainly got the art of experimental s film to a T – metaphorically and literally (See: THE STUFFED SHIRT film of hers). When viewing a film of hers I was always intrigued as to the thought process that drove such exceptional ingenuity. I was lucky enough to interview her and find out.

Very briefly, for those who have not heard of your art before. What would you describe it as?

I work mainly in experimental film, art films, and experimental documentary. By ‘experimental documentary’ I mean something that is in between straight documentation, visual anthropology, surrealist films and everything that escapes the conventional definition of 'documentary' but has, somehow, a deep relationship with the observation of phenomena and performances that involve the production of moving images in real time.

Now you studied media and film extensively. But what initially inspired you to get into this field?

When I was a child, my parents allowed me to stay up late at night only if there was a good movie on television. We would go to the video shop together with my father, which was also a bit of a ritual. This helped me to develop a 'taste' in film, and visions in general quite early on. Also, my mother and father had always been very attentive towards the cultural offerings I was exposed to. This doesn't mean they prohibited me to watch this or read that thing. It was quite the opposite – I always had a lot of freedom, but they were always present. They were always explaining, contextualizing, and entertaining themselves and I with irony. They had been the first and most important trainers of both my eyes and mind. And now, the more I grow up, the more I realize how important and inspiring that was. I now have a different look towards things, to be autonomous in my thinking. This is what led me to be an artist and this is what they taught me.

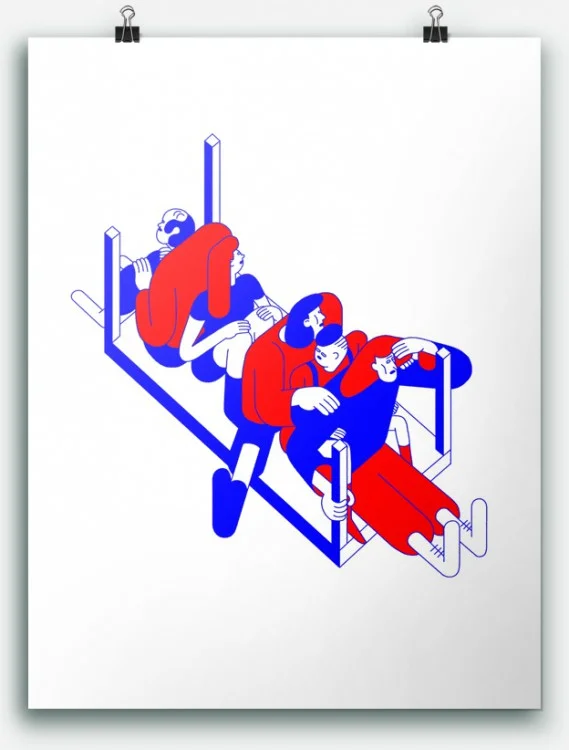

Anna Franceschini, The player may not change his position, HD video, installation view at Spike Island, Bristol, UK, 2014

What aspect of your work do you think defines you? In other words, what do you think makes you a unique artist?

I never thought about myself in terms of uniqueness, but I would say that my aim is to focus on some inherent characteristics of the film language like: movement, montage and light. I'm also interested in cinema not only as a form of art or entertainment but also as a technique – an apparatus. Besides this, I'm interested in a sort of 'cinematic experience' that encompass different aspects of life and experience. Traveling by modern means of transport, taking a escalator, watching the effect of the wind, living in a urban landscape. Everything that belongs to modernity, historically intended, is somehow cinematic. It's not by chance that the first experiments with moving images and the beginning of the modern era are coexistent. Modernity is cinematic and cinema is modern. Which makes the term ‘seventh art’ a little obsolete now. But all this is occurring in a beautiful way though. Cinema is aging gracefully.

You are a very visual artist as well as a filmmaker. Would you consider your art to be a viewing experience for pure aesthetic purposes or something else?

It's a very crucial question and answering it is quite complicated. The esthetic experience it's way more than the mere experience of 'beauty', it involves perception, rational thinking, emotional reactions, all that concerns the self and the Other. I think art has been mainly based on the form rather than its contents – otherwise it turns purely informational. Jean-Luc Godard used the expression 'politique des formes' and I think it's a perfect synthesis for what art is.

Lastly, what’s your creative process like?

It usually starts when a thought meets something that belongs to the so-called ‘phenomenological reality.’ It's an encounter between my subjectivity (or some aspects of it), and what I consider the 'outside.' It’s based on a process of identifying which is often subconscious. Then I interiorize these ideas and rationalize them in order to achieve a result.

Anna Franceschini, Polistirene, video, still, 2007

Lesley Hilling : A Silent Way

An interview with artist Lesley Hilling ahead of her new show In A Silent Way in collaboration with Anders Knutsson.

Lesley Hilling is a contemporary artist who utilizes reclaimed antique wood to create her intricate and alluring sculptures. All of her materials have past lives, some of the objects she has included in her work include: bowling balls, lenses, saw blades, syringes, chess pieces, mirrors, and photographs. Each of these objects bring a new dialogue to the already complex plethora of interweaving stories present.

In 2013 Hilling created the character Joseph Boshier, and attributed her new exhibition to the fictional architect. The tragic story of fame, failure, and disgrace was believed by many, and can be read about in depth here: http://www.josephboshier.co.uk

BM – your work is very haptic and tactile, not only in the way it is produced, but also in the way it invites touch. Is this something you allow or would you rather the work is viewed only by the eyes?

LH – I go for that on purpose, and I’d like it to happen a lot more. I think that’s something quite important.

BM – In the Boshier exhibition there were little doors with things behind, often people think they aren’t allowed to touch an artwork. Does a lot of the detail go unseen because of this?

LH – When I did the Boshier show I was actively encouraging people to explore the works. It was about ‘what lies behind’ etcetera.

BM – That resonates nicely with the alter ego you’ve created.

LH – Yes, I think so, it was intended as another layer. Having people looking at them closely is a really important element. I started putting magnifying glasses and lenses in as well, so that as you moved around, the photographs inside became distorted. It’s all to do with memory, and how the memory distorts.

BM – How much of the aesthetic of your work is dictated by the original appearance of the materials, do you use existing joints and cuts or do you make them all yourself?

LH – I cut all of the joints myself. I think the work has two different sides, there are the pieces that are all antique wood jointed together, and there are the larger Joseph Boshier pieces. The Boshier ones are a cladded substructure. If it all goes horribly wrong I can just re-clad. So it’s only really the colour or the texture that dictates how the piece would come out, rather than the shape.

The Boshier pieces are a lie, whereas the others are quite truthful.

BM – Something very obvious in your work is your love of balance, both with colour and also with the precariousness each piece suggests. Is this something you do intentionally or is it something that happens more instinctually? A lot of the pieces look like they shouldn’t be able to stand unaided.

LH – That’s right and I love that. It’s amazing how they do stand. I think its about 40% me and 60% something else, I’m not quite sure what. It’s a bit dangerous. The bigger pieces are in sections, so when we’re photographing them or moving them and they are not in their complete form, they can fall over. The top section will balance the piece perfectly when in position, but the piece isn’t balanced without it and is liable to fall.

BM – Is the process of creating artworks for you cathartic or do you find it stressful?

LH – Both. Its interesting, because at the end of the Boshier documentary Derval reads out the last entry in his diary, and it says “My art has seen me through”, which does suggest how cathartic it has been, and I think it’s true. I can be one hell of a nasty, bad-tempered person if it’s not going well. My partner Nel knows when things aren’t going well.

BM – Your work gives off a very ‘mad scientist’ kind of vibe, do you think there are elements of that in your character? This seems to be what you have written about the Joseph Boshier alter ego. How akin are the two of you?

LH – Not at all. I’m so modern and young. I’m very up-to-date with things. I’m certainly not mad, I’m a bit reclusive maybe. (Laughs)

BM – A lot of artists are, I think you have to be.

LH – I’ve been with Nel for 32 years this year, so I’ve always had someone around, coming home from work or pottering about the house. She’s creative too, and we’re part of Brixton Housing Co-Op, which is the LGBT community. I know everyone around here, and there are loads of artists and poets. It’s full of creative people. So although I’m reclusive I still have a network of friends around me.

The Joseph Boshier character was a real recluse - his story was about guilt, loss and longing. Emotions that are important to me and my work. Maybe that’s why they have that Mad Scientist look about them.

BM – What do you think the connection is between the LGBT community and the arts community? Do you think its because artists are quite liberal and free?

LH – Maybe liberal, but also maybe damaged. A lot of people who do art are damaged in some way. We’re all a bit damaged I guess. Now it’s quite open to be a lesbian or a gay man but when we were young it was really difficult to come out. Years before that it was illegal. I think all that feeds into people wanting to have a creative outlet. There is definitely that correlation between artists and queers.

BM – Do you believe in the ‘Tortured Artist’ dialectic?

LH – I don’t know, I’ve never really thought about it. A lot of artists have emotional baggage they are working out in the art and it makes it that much more interesting. Also I think people who can create convincing political work and those who come from cultures where they experience oppression, bring so much more to the work.

BM – Maybe the past experience of hardship is what differentiates a good piece of artwork from a good piece of craft?

LH – If you have all of that going into it, it really does help.

BM – Do you think there is still a disparity between women and men in the art world?

LH – I suppose there is, there is in the world isn’t there? Not so much in the west these days though. I think there are so many great women out there doing really great work.

BM – You are using what some would call a traditionally ‘masculine medium’, do you think that’s why you chose a male pseudonym?

LH – Actually I’ve always wondered what it would be like to be a man. My dad was always doing woodwork and things, he built a boat in the front garden. So as a child I was always doing that with him. I’ve always had that interest. When people who don’t know me see the work that do assume I’m a man because Lesley can also be a man’s name.

BM – How much did you have to get into the Boshier mindset whilst creating the work, did it have any adverse effects? Did you start thinking like him? And did you create the works for that show or were they existing works?

LH – Yeah a lot of them were already existing, and I think that’s why it worked. I borrowed a lot of previously sold work so it was a bit like a retrospective. I don’t think I could have made the pieces specifically for the show. Joseph came out of the work, the work couldn’t have come from him.

BM – In your opinion, is the whole story, and the reactions from the press and the public part of the artwork itself, or is that all just auxiliary and a means of publicizing the show?

LH – Yes, it was part of it. The story was like another layer on top of all of that wood. The success of making up a story like that is dependent upon the reaction. In a way I felt it was slightly flawed, because so many people left thinking Joseph Boshier really existed. I wanted people to leave the show doubting.

BM – Did anyone come out of the woodwork genuinely claiming to have known him?

LH – Yes, we had someone claiming to have heard of him. A magazine also wrote an article and I don’t think they realized he didn’t exist.

BM – What has been the single piece of artwork or exhibition that has affected you in the most profound way?

LH – Chris Ofili, his work when he won the turner prize. I really love soul and black culture. I felt his work was saying “OK you can do anything” and I found that so inspiring.

Lesley Hilling's new show In A Silent Way is a collaborative show with Anders Knutsson and is on at :

The Knight Webb Gallery, 54 Atlantic Road, Brixton SW98PZ

6-27 June

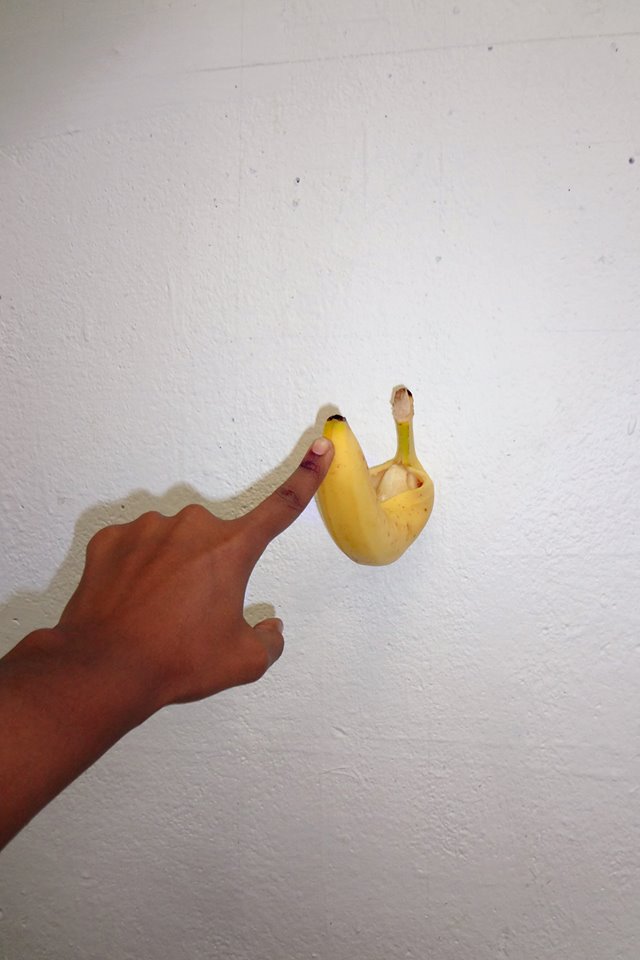

Pictoplasma Festival 2015 | An interview with cofounder Lars Denicke

This week the world’s leading and largest Berlin-based conference and festival of contemporary character design reopened its doors for the eleventh year running with a playground of character designs for us to feast our eyes on.

This week the world’s leading and largest Berlin-based conference and festival of contemporary character design reopened its doors for the eleventh year running with a playground of character designs for us to feast our eyes on. Kicking off with a talk by Helsinki based director and animator Lucas Zanotto, the festival showcases a plethora of talks, workshops and exhibitions by a stellar lineup of international artists, animators, graphic designers and more.

I caught up with co-founder Lars Denicke to chat about the festival, its origins and why Pictoplasma is that little bit more special than your average conference.

Pictoplasma and character design seem to embody a huge variety of different mediums, practices and domains, how would you best define the terms?

Characters aim at our empathy and emotional involvement and function around the very essence of what makes something an image: that it gives us ourselves, the feeling of being looked at. They often have an animist quality, as if they were real and alive, or at least create belief in a virtual existence, as a character in a play.

Characters also function on the principles of abstraction and reduction, as if they were typographic characters, taking away all arabesque details and contexts to maximize a common denominator for us to relate to, neglect of cultural difference. A post-digital play with media is a common strategy; artists and creators play with the same character design in different media. Many, for example, have a digital background for creation, and a longing to leave it behind and experiment with more permanent media. Staging the same character over and over again gives it a virtual identity, each single picture adds to depict this virtual character that supposes to exist somewhere else

How can we use character designs as tools to improve our own understanding of the real world?

Firstly, it’s hard to define the real world, but it is true we feel characters play with our understanding of reality in creating the virtual. Given this, they can increase our understanding of realities being relative to others, interdependent, constructed and not solidly defined. In their animist quality, they tickle us to reflect on the essence of what being alive involves.

“They tickle us to reflect on the essence of what being alive involves.”

Tell me about the initial stages of Pictoplasma and then the Festival, how did it develop? You began as an online and print based publication, right?

In1999 Peter started Pictoplasma as a research website, he came from animation and was looking for a new generation of characters that were more appealing, with fewer targeted audiences, less slaves to the ever same narration. This led to publications.

In 2004, coming from cultural studies and inspired by discourses of the iconic or pictorial turn, I joined Peter with the idea to make a conference out of it. We were looking for a way to present the loud, varied and playful aesthetics in a modest setting, so we thought a conference and not a festival or convention would be best. Just 40 minutes for an artist to talk about his/her creation. We managed to stick to this formula, as these talks get very personal – there is always a reason why someone creates these characters, and it gets through in every talk. Gallery exhibitions and animation screenings were part of this event from the very beginning, which made it a festival.

From 2006-2009 we started to produce ourselves, firstly giving characters designed by other artists a corporeality through the hands of costume designers who passed them on to dancers to discover how a character would change personality when having a certain body; then with installations that played with the idea of creating a world for us to get immersed - this culminated in the exhibition Prepare for Pictopia (2009, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin).

In 2010 we created the Missing Link, a character reflecting on the Yeti myth, and investigated artistic strategies of community, tribes and following in the digital age; this led to the exhibition Post-Digital Monsters (2011, La Gaîté lyrique, Paris). In 2012-13 we focused on characters in visual communication, the terror of photographic realism, and the commercial character as mascot, (White Noise, La Casa Encendida, Madrid 2013).

And then in 2014, the celebration of a decade of the festival was done in correspondence with the time-honoured genre of the portrait gallery, again giving each character that shaped our festival a place in an exhibition that performed the idea of being pre-digital, as in much earlier, or a memory of the digital age, as in much later.

NICOLAS MENARD

What makes Pictoplasma different to other conferences?

Pictoplasma encompasses all design practices – we don’t make a difference as such, we just follow characters, not the artists or concepts. Therefore it is open to all, it is not an elite fine art club as such. The contexts give the creation to the characters and we are accessible to all.