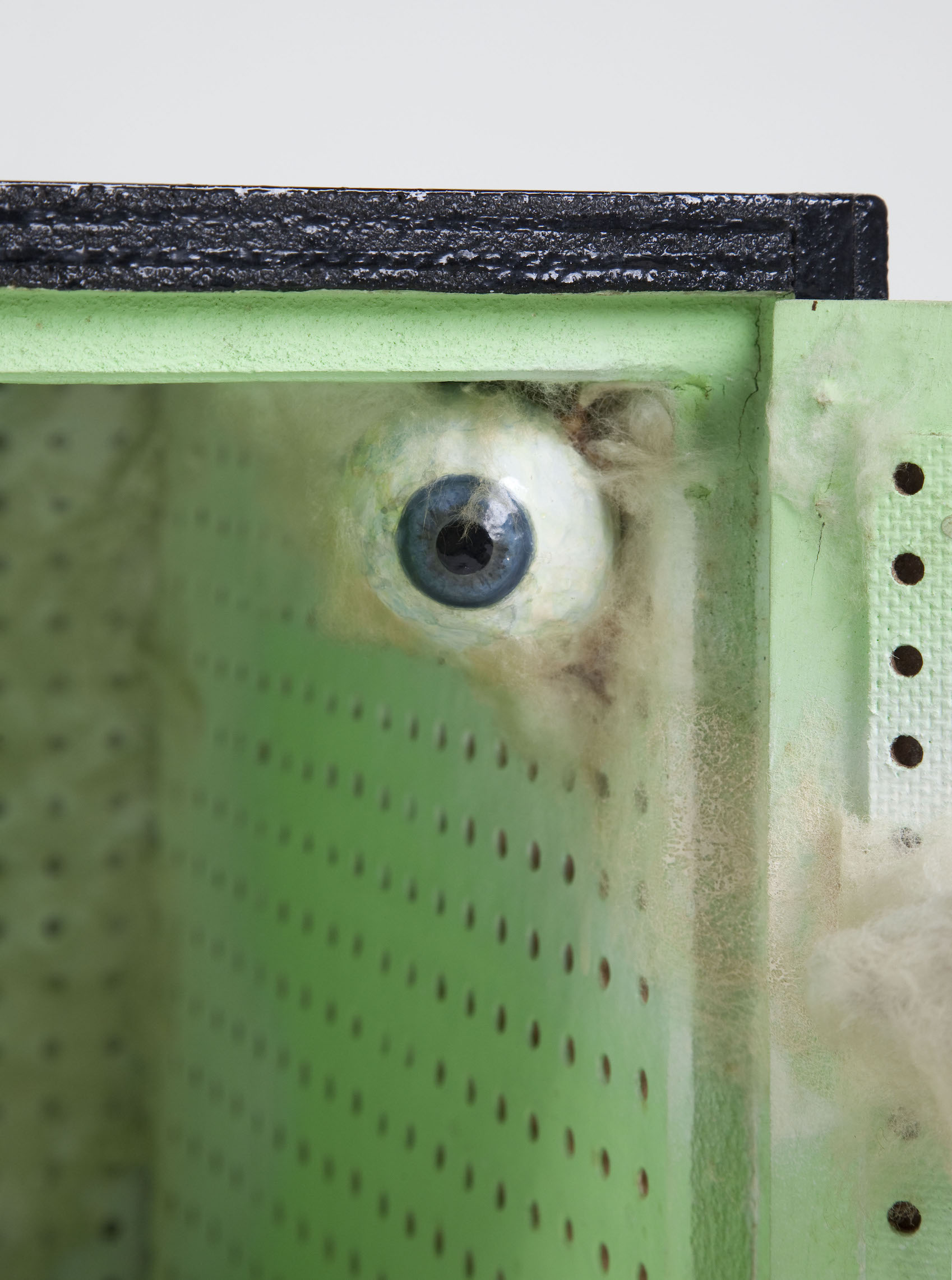

Solitary by Patrick Colhoun at the Ben Oakley Gallery

With exhibition ‘Solitary’, contemporary sculpture artist Patrick Colhoun introduces his new take on the dark nature his previous works dealt with, going from grievous to playful in an utterly unique way.

With exhibition ‘Solitary’, contemporary sculpture artist Patrick Colhoun introduces his new take on the dark nature his previous works dealt with, going from grievous to playful in an utterly unique way.

When an artist is capable of expressing himself through his works of art, transferring his feelings to objects and sculptures and translating even the darkest thoughts into every little physical detail; that is when art has reached its greatest version. The man that stands by this method and masters it simultaneously is contemporary sculpture artist Patrick Colhoun.

“I have a strong belief in myself and my work. I am confident that my work has the potential to stand out and as long as I can keep making that sort of work, I will keep progressing. How far though, in this game, is anyone’s guess.”

Patrick Colhoun’s art is known for treating dark subjects such as death, decay, sexual deviancy and aggression. Dealing with grief and difficult encounters he has experienced in the past, many say the work he produced in his previous years has been a way to express his emotions, portraying them in an extreme and mesmerizing way.

Today, 6 years after his last solo exhibition, Patrick’s creations have taken another turn, shedding a light upon his previous work and changing the atmosphere from grievous to playful. The exhibition: Solitary is the third part of a series of 3 exhibitions. Having taken place at Belfast and Dublin, it is now London’s turn to be wow-ed by the artist’s ability to move with sculpture. The exhibition still deals with memories from Colhoun’s past, however this time he highlights the parts he likes remembering. Solitary combines contemporary sculpture and mixed media to create something that Patrick calls ‘anti-ceramics’. Striving upon the idea of being unique, the artist surprises every time, may it be with unseen material combinations or objects that are as far removed from ceramics as possible.

“I want to do ceramics, but not as you know it. I started introducing other materials to the ceramic base, including latex, neon, hosiery, spikes and piercings, all things not usually associated with traditional ceramics.”

Solitary will take place at the Ben Oakley Gallery from the 13th until the 29th of November.

The von Bartha gallery hosts Bernhard Luginbühl and friends

The works of one of Switzerland’s best known sculptors, and a few of his fellow contemporaries are erected in all their glory at the von Bartha gallery.

The works of one of Switzerland’s best known sculptors, and a few of his fellow contemporaries are erected in all their glory at the von Bartha gallery.

If you live in Zürich, there’s probably no doubt that you’ve heard of Bernhard Luginbühl. And if you’ve walked down Mythenquai road you definitely would have seen De Grosse Giraffe (1969) – a great iron sculpture, with its magnificent curved beam looming over Zürich like a watchful sentry.

The sculptures of Bernhard Luginbühl (1929 – 2011) can be seen erected not only in Zürich, but in Hamburg and Muttenz too. He was an expert craftsman – who had a particular penchant for producing sculptures from scrap metal. Aside from Eduardo Chillida, he was one of the first to pioneer the iron sculpture from the 1950s, which is arguably what raised him to prominence in the art world.

A large portion of his earlier work no longer exists – due to Luginbühl destroying or burning some of them. This ‘creative arsony’ rekindled itself in his later work, from the mid 1970s, where he burned several of his wooden structures in ceremonious artistic fashion.

But of particular note were his fascinating collaborations with contemporaries Dieter Roth, Jean Tinguely and Aflred Hofkunst, who feature in this upcoming exhibition. Sculptures like HAUS (1979-94) are comprised of iron and wood, brushes and bone – showcasing his playful yet masterful ability to combine media into something to marvel at.

While some of the collaborative sculptures such as Schluckuck (1978 – 1979) look like condensed, complicated rube-goldberg machines, the exhibition displays some of his solo works too. Expect to witness his ink drawings as well as the fantastically mechanical, yet abstract Kleine Kulturkarrette II (1975) – which is more than just a colourful cabinet on wheels.

Bernhard Luginbühl and Friends will run from 4th September – 24th October 2015 and the preview will be on September 4 from 5-8pm.

Address:

von Bartha, Kannenfeldplatz 6,

4056, Basel, Switzerland

Opening Hours:

Tuesday to Friday 2-6pm, Saturday 11am – 4pm or by appointment.

Tetsumi Kudo at Hauser & Wirth London

A seminal figure in Tokyo’s Anti-Art movement in the late 1950’s, multidisciplinary artist Tetsumi Kudo (1935 – 1990) left behind a lasting legacy: this autumn, Hauser & Wirth London will host an exhibition of his works, marking 25 years since his passing.

A seminal figure in Tokyo’s Anti-Art movement in the late 1950’s, multidisciplinary artist Tetsumi Kudo (1935 – 1990) left behind a lasting legacy: this autumn, Hauser & Wirth London will host an exhibition of his works, marking 25 years since his passing.

The exhibition will present a selection of work dating from the first ten years that Kudo spent in Paris (1963 – 1972), following the completion of his studies at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts in 1958.

Although marginalised in North America and Europe for many years, Kudo’s influence on subsequent generations of artists has been profound and far-reaching. The artist spent the majority of his career preoccupied with the impact of nuclear catastrophe and the excess of consumer society associated with the post-war economic boom, his interest in these topics intensified upon his exposure to the European intellectual scene.

Developed in the context of post-war Japan and France, Kudo’s practice, which encompasses sculpture, installation and performance-based work, is dominated by a sense of disillusionment with the modern world – its blind faith in progress, technological advancement, and humanist ideals.

Consisting of a die enlarged to over 3.5 square metres with a small circular door allowing the viewer to climb into the dark interior lit with UV light, ‘Garden of the Metamorphosis in the Space Capsule’ will form the exhibition’s focal point, shown alongside examples from his cube and dome series.

In his cube series, small boxes contain decaying cocoons and shells revealing half-living forms – often replica limbs, detached phalli or papier-mâché organs – that merge with man-made items. These sculptures were intended as a comment on the individualistic outlook and eager adoption of mass-production which he found to be prevalent in Europe.

Kudo’s dome works appear as futuristic terrariums: perspex spheres fed by circuit boards or batteries house artificial plant life, soil, and radioactive detritus. What is being cultivated in these mini eco-systems is a grotesque, decomposing fusion of the biological and mechanical, illustrating Kudo’s feeling that with the pollution of nature comes the decomposition of humanity.

The simultaneously political, yet highly aesthetic, characteristic of his sculptural work is at the centre of the contemporary oeuvre.

Tetsumi Kudo

Hauser & Wirth London, North Gallery

22 September – 21 November 2015

Opening: Monday 21 September, 6 – 8 pm

Ai Weiwei – Creating Under Imminent Threat

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is as well known for his art as for his activism. A steadfast critic of the Chinese government, Ai has been denied a passport for over four years and has been unable to leave or exhibit work in his native country.

Photograph by Harry Pearce Pentagram 2015

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei is as well known for his art as for his activism.

A steadfast critic of the Chinese government, Ai has been denied a passport for over four years and has been unable to leave or exhibit work in his native country.

Recently Weiwei posted a photograph online of him holding up his newly returned passport and announced that he has also been granted an extended six-month visa to visit the UK, which he will coordinate with his Royal Academy retrospective.

On the 19th of September 2015, The Royal Academy will host the first major retrospective of his work, showing works from his entire oeuvre. From the smashing of a Han Dynasty vase (which will appear in the show), to the poignant critique of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that killed over 5,000 Chinese children, Weiwei’s work is bold, controversial and unforgiving.

All the works in this show have all been created since 1993, the date when Weiwei returned to his native China from America. This exhibition will show works that have never before been seen in this country, and many have been created specifically for this venue, Weiwei navigating the space digitally from China.

Often labeled as an activist or a political artist, this social conscience is what has influenced most of his works to date. Living under constant imminent threat from those with absolute authority, Weiwei’s work is created out of adversity and struggle. His oppressors are ones who are able to work above and therefore outside the law, and for that reason his struggle is a very real one. Despite this, Weiwei will not be defeated, and continues to critique the government and its actions towards the Citizens of his beloved China.

In a career spanning over three decades, his hand has also been turned to: activism, architecture, publishing, and curation, in a tour de force of creative activity. The artist worked alongside Herzog & de Meuron (the same company to design the Tate Modern in 1995) to design the 2008 Beijing National Olympic Stadium (commonly known as the Birdsnest). This project was born from a building Ai designed nine years before, when he needed a new studio, and decided to simply build it himself.

This confident disregard for convention is the attitude with which he approaches all of his work, and it has gained him many critics. The most notable of which being the Chinese government themselves, who have arrested him, seized his assets, terrified his wife and child, tracked him daily, tapped his phones, and rescinded his passport.

Perhaps most well known for his Sunflower Seeds artwork, in which he filled Tate Modern's Turbine Hall with 100 million porcelain sunflower seeds. Each seed was hand crafted and painted by hundreds of Chinese citizens from the city of Jingdezhen, in a process that took many years. Visitors to the show were overwhelmed to see the vast expanse of seeds, and were originally invited to walk and sit upon them, interacting with the work in a way in which we are rarely allowed to. (For safety reasons this was later disallowed)

The sunflower seeds appeared uniform but upon close inspection revealed themselves to be minutely unique, created using centuries-old techniques that have been passed down through generations.

In the Chinese culture sunflowers are extremely important, Chairman Mao would use the symbology of the sunflower to depict his leadership, himself being the sun, whilst those loyal to his cause were the sunflowers. In Weiwei’s opinion, sunflowers supported the whole revolution, both spiritually and materially. In this artwork, Weiwei supported an entire village for years, as well as creating something that promotes an interesting dialogue about the very culture that created it.

Weiwei’s work is about people, about the often nameless many who are oppressed or ignored. It is about justice for those who have been abandoned or neglected by those who are there to protect them, and it is most primarily about their basic human rights.

It is tragically ironic that those human rights that he has worked so tirelessly to protect for others are those denied him by his own government.

The Royal Academy has turned to Crowdfunding to help raise £100,000 to bring the centerpiece of the exhibition to Britain. Weiwei’s reconstituted Trees will sit in the exterior courtyard and be free to view for all. The campaign has just over a week left and still needs to raise just over 25% of its target.

Get involved here

The show will be on between

September 19th – December 13th 2015

Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BD

All images courtesy of Royal Academy

The work of Javier Martin holds up a mirror to society – and on occasion, the mirror is literal

Javier Martin works with paint and sculpture in a manner that explores our current social climate incorporating fashion portraiture, recognisable brands, gun violence, climate change and money.

The work of Javier Martin reaches out to you in many ways. His early painting and digital print work merges ‘iconic’ fashion imagery, taken by himself, with brand imagery and currency. The model’s eyes are covered signifying some sort of ‘blindness’ towards the subject matter Martin wishes to convey. With similar messages, Marin’s installations and sculpture takes a more minimalist route in regards to aesthetic and visual quality.

Favouring the colour white, Martin’s installations see the human form become a blank canvas – his figures, clothed fully in white from head to toe, make any signifiers of personality or identity unrecognisable: they become robotic, uniformed figures. This forces the viewer to focus upon the actions these figures engage in or the positions they are found in. For example, ‘Portrait Inverted’ sees a figure falling into, or out of, a framed white space on the wall. ‘Man that is born of the earth’ finds this figure with a wooden branch-like head protruding from the earth, on all fours, as if forcibly attached to the land.

Martin’s installations reflect the art onto the viewer: the art is as much about the viewer as it is about the artist or the art. Mirrors are frequently used by Martin to place the viewer in the artwork, as a central figure around which the concepts discussed revolve around. ‘Social Reflection’ sees another while figure with a mirror for a face begging for money on the street. ‘Money? Where? Money? Who? Money? I?’ finds a larger-than-life one dollar bill hanging on the wall, and where one would usually find George Washington, one discovers themselves surrounded by the ornate decoration upon the currency.

The use of material and form by Martin is clever in that it can often ‘trick’ the viewer into finding reality in a situation where there is trickery. The bending, melting and protruding of material in works such as ‘El Pacto’ or ‘Climate change of design’ creates new dimension to the work. This is to the point where the crafting of these objects so seamlessly is to be highly admired.

Whilst some of Martin’s earlier works deal with printed and painted mediums, all of his later works bring the artwork out further towards the viewer. In installation and sculptural works, this is most obvious, but even in other photographic work and painting or drawing, an effort has been made to make the work more 3-D. Martin’s ‘Print Cuts’ alter photographic material to form the figures photographed as a web of material. Keeping these images suspended away from the wall in the frame allows the light in a space to interact with this web, casting shadows. In ‘Blindness Light’, Martin attaches neon lighting to edited photographic portraits, to cover the eyes of the figure and follow various contours, playing with colour and light.

Martin’s attachment to the ‘iconic’ fashion and modelling imagery with his artistic alterations has seen him collaborate with several fashion and art-based publications, creating imagery that lends itself to the glossy printed format.

Mark Mcclure | Neatly Ordered Abstraction

Mark Mcclure is an artist who utilizes reclaimed wood to create precise geometric artworks. Check out the interview by Benjamin Murphy

Mark Mcclure is an artist who utilizes reclaimed wood to create precise geometric artworks. Using both painted and untreated woods; his works have a crisp yet raw feel that exist symbiotically to create an ordered and balanced work. Sitting somewhere between sculpture, collage, and painting, his work is best interpreted when viewed in its relation to Constructivism.

BM – You combine both old and new materials in your work. Does the history of the materials ever dictate the aesthetic of the piece?

Not really. I tend not to do things that way round. I choose the materials for their colour & texture - in the same way a painter might choose from a selection of paints or charcoals. Texture, colour, and any remnants of past use - all contribute to a pretty broad palette. If I’m after specific textures or remnants to use - then I might stain the wood to adjust the colours slightly - but the history of materials never really takes priority.

BM – There is a conflict between form and functionality, which do you think takes precedent?

It’s interesting that you’ve preloaded the question suggesting that form and function are independent of each other. To me it’s all a sliding scale depending upon the context of a piece.

If I’m creating a wooden mural then it would automatically adopt the function of a wall surface - whilst also being an artwork. If I put a hinged door in a sculpture - it becomes a cupboard of sorts. It might be a bloody expensive & abstract cupboard - but it’s still got the potential to be a cupboard. It’s down to the context of the artwork - who owns it, how they perceive it, probably how much they paid for it as well.

BM – You have mentioned to me before that you would identify yourself as a constructivist. The Constructivists believed that the true goal was to make mass-produced objects. Your work is very hands-on, how would you feel about others making it for you?

The Constructivists had their own in-fights over the ideas of mass production. The likes of Rodchenko straddled the worlds of art & design - whilst others such as Naum Gabo believed in a purer approach that didn’t cross over into function. For me that goes back to the sliding scale & context of the artwork.

But mass production is a different beast to having other people involved in making artworks. The Uphoarding wall I created at the Olympic Park last year involved up to about 10 different people over a 10 month period - and in the future I’ll make artworks in materials I will never have time to master myself - concrete, metal etc. - So it’s inevitable that others will end up producing some of my work.

BM – Would it still feel like your artworks if you didn’t get your hands dirty?

Yes - but without the emotional attachment that comes from being so involved at every step - an attachment that probably stems from the craft side of things. They’d be put on a different shelf in my mind - but they’d still be mine.

BM – What makes the Constructivists artists as opposed to craftsmen?

Many of them were craftsmen - in that they strived to be masters of their materials - producing clothing, design objects etc. with a view to targeting a consumer market. Others had less tangible, idealistic aims - challenging or celebrating aspects of the world they lived in - expressing feeling and emotion etc. and I guess that’s what makes them artists.

BM – The Constructivists’s aim was to make artworks that force the viewer to become an ‘active viewer’, how interactive is your work and do you intend for it to be touched?

Interaction is really important and working in such tactile materials has meant that it’s hard not to touch a lot of my work - which is totally cool. I love the idea of artworks in galleries being more playful and interactive - though interaction doesn’t always have to involve touch. This is something I’m going to play with more this year…. some exciting ideas on the cards.

BM – When you clad the floor or a wall, do you see this as a two-dimensional or a three dimensional piece?

2 dimensions. I’m not too sure where the tipping point is - probably somewhere around 4 inches thick.

BM – Is collage then 2D or 3D? Would you say your work is a type of collage?

Potentially both - can we invent dimensional fractions here & now? 2.3 dimensions? I wouldn’t say my work right now is collage… though it has been. Collage to me is more layer upon layer than piece by piece - and involves a lot more glue.

BM – What exciting future projects are you working on?

A nice mix right now - a large bespoke floor and a few other fun pieces towards the ‘function’ end of that sliding scale we mentioned earlier - and also some new artworks for exhibitions & fairs over the summer. I’m also exploring some materials to add a new aspect to my work later this year. Some busy & exciting months ahead.

More of Mark’s work can be seen online at www.markmcclure.co.uk

Maeng Wookjae is the Big Game Ceramic Hunter

Enter into the mind of one the most exciting up-and-coming South Korean artists of our time.

In some pieces, Maeng Wookjae adorns his ceramic animal sculptures on wooden plaques that resemble the severed heads of big game. The kind you would see in a trigger-happy Safari hunter’s lodgings. But they’re not the installations of a taxidermist. They’re ceramic, and thus fragile, just like the wild and vulnerable animals that Wookjae sculpts.

Auguste Rodin once said, “nothing is a waste of time if you use the experience wisely.” His words could not be more relevant than to Maeng Wookjae – who’s artistic expression was found during his time spent travelling to North America. I interviewed the South Korean artist himself, and his environmental conscience struck me just as potently as his sculptures do.

What is the significance of the gold eyes in your ceramic sculptures?

They can be shown to audiences in several ways. First, people can see themselves reflected in the shiny gold eyes. The scenery on the eyes represents our very plentiful environment, which can be compared with a plentiful environment for other creatures too. It also represents how the animals look from our human perspective. The colour of gold doesn’t always seem cold because it is metallic – there is warmness in it.

Would you say that one of the biggest turning points of your career were your visits to North America? If so, why?

Yes, my work changed after visiting North America. I went to a residence program called the Archie Bray foundation, after finishing my M.F.A in Korea. The environment was quite rural in comparison to life in Seoul, which is a very crowded city. I had wondrous, fresh experiences such as several chances to meet wild animals face to face.

For example, a friend of mine and I drove to another friend’s house and there was a deer on the narrow road. Usually wild animals run away from people but the deer was standing in the middle of the road. The deer looked at the ground and us several times. When I looked closer, I saw a dead baby deer. I can’t still forgot the moment of having eye contact with the mother deer.

Another moment I strongly recall was a time where I was on the way to home and found a huge dead deer by the road. I felt so sorry and immensely sad. At that time, some teenagers walked through the area and one guy loudly said something to the dead deer and spat on its carcass. I was really surprised and I tried to understand that situation. I thought maybe a wild animal injured one of his family or friends.

And then I started to have a deep concern about the relationship between humans and animals. I continued my North America trip with a residency at the Banff Centre in Canada. And I had more priceless experiences with wild animals.

Let’s talk a little bit about your most recent work – Family. What was the creative process and inspiration behind that?

It began with the thought “Are we a family?” I combined humans and other life forms on the works. Some people see the work; view it positively, friendly and relate to it. I wanted to lead people to think and talk about our environmental conditions with other creatures.

Have you noticed a difference between the reactions of your Western and Far-Eastern audiences? In other words – how do Americans and Europeans react to work in comparison to Koreans?

From what I’ve seen, the western audience are more interested in my works than Koreans. I think it’s because of the difference in perspective about how both cultures view art. My works focus on presenting social issues and environmental issues rather than an expression of beauty. Young people in Korea show an interest [in my work], and try to understand my expression, but a lot of the older audience don’t think it’s an art piece. They might just think ‘it’s not related to my life’, although my works tell a story about universal issues. The art market in Korea is small and restricted to the very famous artists. But it’s beginning to get better now.

As well as being represented by the Mindy Solomon gallery like you, Kate MacDowell’s work is rather similar to yours. I wanted to ask you if you would you consider doing a collaborative work with her?

I’ve seen her artwork on the web. And I like her work. It could be interesting to do something with her – I think it’s always good showing works together that convey similar themes.

If you had to choose, who are your top 5 favourite contemporary artists?

Anish Kapoor, Antony Gormley, Damien Hirst, Olafur Eliasson, Clare Twomey.

What can we expect from Maeng Wookjae in 2016?

Recently, I’m trying to make an exhibition through an installation. I find that installations are a more effective way to connect my works to audiences. So I will challenge myself to make this creative way of expression.

Alexander Calder’s mobiles come to life at the Tate Modern

The UK’s largest ever Alexander Calder exhibition of kinetic sculptures is coming to the Tate Modern. And in more ways than one, it’s moving.

Alexander Calder (1898 - 1976)

Antennae with Red and Blue Dots 1953

Tate © ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015

Within art circles, if you were to mention the ‘mobile,’ there are no names that spring to mind other than Alexander Calder (1898-1976) – who is renowned for having invented these ingenious, performing sculptures.

Having amassed an impressive portfolio of work that spanned several decades, a large portion of Calder’s work is being brought to the Tate Modern for the UK audience to marvel at. The exhibition, entitled Performing Sculpture, will showcase about 100 of the American artist's works between his formative years from the late 20s to the early 60s where he had established an illustrious career.

Achim Borchardt-Hume, the Director of Exhibitions at the Tate Modern and co-curator of this exhibition, stated that Calder was ‘responsible for rethinking sculpture’ when referring to his innovative invention of the mobile. He went on to add that with regular sculptures, one must glean everything they can by moving around it – but Calder ‘made sculpture move for us.’

He further conflated Calder’s sculptures with the performance arts, stressing how important this field contributed to Calder’s work. Pieces like Dancers and Sphere (1938) showcases motion in a way similar to children playing whereas Red Gongs (1950) is a mobile that introduces the sound of a brass gong – showing how well he managed to take performance to another level.

Performing Sculpture will also feature Calder’s Alexander’s famed wire sculptures of his artistic contemporaries and friends, including a wired portrait of Joan Miró suspended in space.

However, perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of this exhibition will be the mechanics of movement behind his mobiles. The slow, cloud-like movement of the sculptures will be powered purely by the airflow in the room. This delicate motion is something that is lost in images, but can only truly experienced in person.

Perhaps the only regrettable aspect of this upcoming exhibition would be the omission of the stage sets he designed when working with choreographer Martha Graham. Nevertheless, this is a necessary omission. The entirety of his performance art is suspended within and between the movements of his sculptures. There does not need to be anyone performing in order to augment the power of his sculptures – because they do all the performing instead.

Fans of modernism, mathematics and the masterful should most certainly attend. This is not an exhibition to be missed.

Alexander Calder (1898 - 1976)

Triple Gong c.1948

Calder Foundation, New York, NY, USA

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015

Alexander Calder in his Roxbury studio, 1941

Photo credit: Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2015

Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture will be running at the Tate Modern from 11 November 2015 – 3 April 2016

Marc Quinn – The Toxic Sublime

White Cube Bermondsey

15 July 2015 – 13 September 2015

British-born artist Marc Quinn is perhaps most well known for his 1991 artwork Self: a life size sculpture of his head, using 4.5 litres of his own blood. Bought by Charles Saatchi for £13,000 in the year of its conception, this work has accrued almost mythical status.

In 2005, Quinn took over the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square with his sculptural artwork Alison Lapper. Alison, who is an artist herself, was born without arms and with incredibly shortened legs. This work showed her nude and unflinching, proud of her nakedness. Deformities such Alison’s are naturally compelling to observe due to their uniqueness. As a species we are intrigued by anything unusual or different, but society tells us we mustn’t. Looking upon such a drastic disability is often thought to be an insult to the recipient, and children quickly learn not to stare.

Quinn's sculpture rejects these social conventions and shows her in all her unique beauty. Placing her on a plinth he shows us that is ok to look (in fact he forced us to do so), and that Alison has nothing to hide. There was no shame in her face. This work was bold, brazen, and brilliant.

On the 14th of July Quinn’s new show The Toxic Sublime opened at the White Cube gallery in Bermondsey. This new body of work is quite far removed from his bodily excretions and his sculptures of those without limbs, seemingly more reserved and delicate.

Most prominent and striking in this show are his stainless steel Wave and Shell sculptures, dotted around on the gallery floor. Highly polished in some areas they are more Cloudgate than Wave, but are beautiful nonetheless.

The other and more subtle works in the show are vast undulating canvasses, affixed to bent aluminum sheets. Upon these canvasses is a mixture of: photographs of sunsets, spray paint, and tape (amongst a myriad of other less determinable shapes). The canvasses once painted are abrasively rubbed against drain covers in the street.

The inclusions of these humble drain covers into the artwork is possibly the most interesting element to the whole show. Something described in the press release as being:

“.. suggestive of how water, which is free and boundless in the ocean, is tamed, controlled and directed by the manmade network of conduits running beneath the surface of the city.”

Quinn’s notoriety was gained in the early nineties for bravely showing the public that which we usually hide: faeces, blood, semen, and the like. Gilded and placed on a plinth for all to see. His earlier work depicted that which lies beneath, where as this show obscures exactly that. The drain cover is an object that hides these very secretions, burying them underground.

Quinn's work is brilliant at showing us the beauty in the overlooked and the grotesque, and this show to some extent does just that. The Toxic Sublime is definitely very beautiful, but it lacks a certain grotesqueness that is a Marc Quinn trademark.

Photographs from Marcquinn.com

White Cube Bermondsey

15 July 2015 – 13 September 2015

Review: Barbara Hepworth, Sculpture for a Modern World Exhibition

Affable, sensual and a bit perplexing.

Barbara Hepworth in the Palais studio at work on the wood carving Hollow Form with White Interior 1963 Photograph: Val Wilmer, ©Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Affable, sensual and a bit perplexing

For ticket holders who aren't familiar with her, Tate Britain's retrospective of the British celebrity sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) cannot compare to the stature of the lady herself. Born in Wakefield, Yorkshire, her passion for art and sculpting led not only to her eventual global fame but also to her future husband and collaborator Ben Nicholson, a relationship that has been at the forefront of this exhibition. After they settled in St Ives, Cornwall, without her knowing it would be where she'd reside for the rest of her life, St Ives' landscape formed a relationship with the lady which is reflected achingly beautifully in the exhibition. The sensuous and balanced shapes and forms embody the fantastic control and craftiness of Hepworth who in this almost biographical exhibition emerges not as an Iron Lady but a lady who carves with iron.

One of the reasons that I called it perplexing is that the selected works are more or less monotonously placed into vitrines that sit awkwardly with the eye level. Locking the tactile sculptures into glass cases could be a kludge to avoid big budget mise-en-scene environmental set up as many of Hepworth's works had been made for outdoors, despite the artist herself had urged that these sculptures were meant to be touched. The staging of the pieces proves to be underwhelming against expectations more than anything considering this has been the first in London in 47 years. This is not an exhibition that aims for spectacles nor is it inventive or imaginative in its presentation of such modernist works. Surely, for the female artist who changed the face of sculpting in a male dominated world of sculptors who refused to be addressed as a sculptress, there could be a bit more rickety to rock her perfectly balanced, sensual and sentient geometric nirvana. With the exception of the last room for “Garden”, the rest do not quite distinguish themselves from an Apple store.

Hepworth in the Mall Studio, London, 1933

Photograph by Paul Laib

The Barbara Hepworth Photograph Collection

© The de Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives, Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

Another reason I was underwhelmed is its lack of narrative. A lot could be said of a woman who went to art school and sculpted through two World Wars and rebelled against the totalitarian regimes of the Europe – there isn't a clear structure of feeling, in contrast to the actions that the artist has taken to ensure the way she is portrayed by the media, including mediating specific environments for photographing her works as well as public displays.

You would however find yourself at peace and properly meditated after a walk-through, because staring into marble sculptures “Two Segments and Sphere” (1935-6) or “Large and Small Form” (1934), will make you helplessly yearn for balance as the pure genius of the weight distribution and craftiness of these sculptures must endure not to fall all over the place and panic viewers. You will genuinely wonder how Hepworth was able to determine where to make hollow or to protrude.

Four large carvings in the sumptuous African hardwood guarea (1954-5), arguably the highpoint of Hepworth's carving career, are reunited for this exhibition, which is also a highlight for me because they command the entire room, looking like four very proud half eaten apples.

Without being able to hype and emphasize one of her most important works "Single Form" (which now resides outside the UN headquarters in New York, due to a what seems to be a convoluted curational process, although it appears to be complacent in repositioning Hepworth as a global giant) Tate Britain however treats Hepworth's superfans with a never before seen experience and reveals not only the aspect of Hepworth that was only known to a few selected private owners but also a bitter-sweetness in the celebration of an English sculptress’ extraordinary life that will leave you filled with beautiful tenderness.

I recommend it for a first date.

Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World is now open at Tate Britain.

24-June – 25 October 2015

Tate Britain, Linbury Galleries

Kunstakademie Düsseldorf alumni come to London

Three graduate sculptors of Kunstakademie Düsseldorf come together with Tony Cragg to bring us their latest work.

Three graduate sculptors of Kunstakademie Düsseldorf come together with Tony Cragg to bring us their latest work.

Coming up at Blain Southern London this month is a sculpture exhibition by Mathias Lanfer, Gereon Lepper and Andreas Schmitten, all alumni of the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. The exhibition is curated by prestigious sculptor Tony Cragg, who is also a professor at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf.

Cragg is an English sculptor who moved to Germany in the 70s, he has exhibited in countless galleries and won many important awards such as the Turner Prize. His work is particularly concerned with material. His earlier work is specifically interested in making use of found and discarded objects and materials. For him material determines form.

Using sculpture, Lanfer’s work looks at form finding as well as public space, Lepper’s work investigates nature’s response to technical intervention and the ongoing transformation of energy, with the addition of Schmitten’s clean sculptures influenced by his interest in film and animation it is exciting to see how the work of these esteemed artists will come together under the curation of Tony Cragg.

The exhibition will run 10 July - 29 August 2015 at Blain Southern, London.

Kate Clements: The bride stripped bare by her bachelors

What makes Kate Clements a truly great artist is the conversation that her work evokes about the female gender and issues of narcissistic female adornment.

To the uninitiated viewer, looking at Kate Clements’ intricate glasswork, it might be easy to dismiss her as simply another talented decorative artist.

Whilst there is no doubt that she is extremely talented at the physical manipulation of kiln-fired glass, what does really make Clements’ work stand out? What makes her a truly great artist is the conversation that her work evokes about the female gender and issues of narcissistic female adornment. Clements’ work goes far beyond obvious feminist debates about woman as object and the power of the female form. Instead, what Clements seeks to uncover is the very psychological reasoning that leads to the cultural construction of feminine identity, and how women’s efforts at fulfilling such ideals can lead simultaneously to feelings of guilt and individual power. Adding to this is her performance work, which examines the ideas of purity and power, using metaphors presented by external objects as a means of examining metaphysical notions of being.

Constructing decorative, non-functional glass headdresses which function as a separation between viewer and ‘wearer’, Clements highlights a persistent desire by women to transcend their physical nature, in the hopes of achieving the socially constructed fantasy of a ‘perfect’ woman. Using such an elaborate and fragile medium adds to the sense of counterfeit perfection suggested by the focus on veils and crowns, key motifs of the beauty queen and the bride. It is this close examination into our cultural constructs and farcical use of adornments that transform Clements’ work into something more than pure decoration, adding layers of meaning that make us examine the very society we live in.

Hi Kate, can you tell us a bit about yourself as an artist? What are your passions? What questions still need answering for you?

I work primarily with glass but I describe my work as sculpture and installation. I have just completed my masters at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia. Over the past two years I have explored the ambiguity of fashion—its capacity for imitation and distinction; its juxtaposition of the artificial and the natural; its ability to divide people by keeping some groups together while separating others and accentuating class division. I’ve come to understand the lifecycle of fashion as a process of creative destruction where the “new” replaces the “old,” yet nothing is truly new.

I am still exploring this and find inspiration in the perspective of critical theorist Georg Simmel whose observations over a hundred years ago remain all too relevant in today’s Gilded Age. “Fashion elevates even the unimportant individual by making them the representative of a totality, the embodiment of a joint spirit. It is particularly characteristic of fashion - because by its very essence it can be a norm, which is never satisfied by everyone...” Style, as Simmel suggests, both unburdens and conceals the personal, whether in behavior or home furnishings, toning down the personal to “a generality and its law.” My choice of materials comments on society’s need to conform and maintain distance.

Let’s talk about your chosen medium. What are the benefits and difficulties in working with glass? How did you first discover your interest in kiln-fired glass?

When I was 17 I took a pre-college course in kiln-fired glass at the Kansas City Art Institute, which was primarily mosaic and plate making. The professor saw potential in me and when I started my bachelors there in the fall I trained as his tech and teaching assistant for the course. I continued that job for my four years in undergrad. Because it was only offered as an elective, I learned the fundamentals through instruction but was substantially self-taught.

Working in glass has pros and cons. The glass community is small and very supportive of its artists. Because of the nature of the material, when you are working with it hot you usually need the help of one to four people to make a piece - so the sense of community is very strong.

A con can be the constant struggle of defending the material. The question of why someone creates paintings is asked much less than why someone works with glass. However, the constant question of ‘why glass’ pushes glass artists to address the relevancy of the material in the conceptual nature of the piece as well a technical one. Working within a craft material there is a wide spectrum of what people choose to do with it. It can range from pipes and paperweights to fine art. If I am speaking to someone outside of the glass world and they ask me what I do and I say glass they normally follow up with asking if I can make a pipe for them.

Breaking outside of the glass community can be difficult too. I would love to be showing in galleries that didn’t only represent other glass artists. Not to get away from other glass artists but so viewers could understand working with glass as fine art and not glass art. This seems to be a line that can be difficult to cross.

What relationships to the female form does your work provoke, and how important is it for you to express these concerns in your work?

I think initially my work was heavily reliant on the female form. As a young woman, I felt the pressures of conforming to some sort of social construct of beauty. At times that has made me feel guilty because I felt a sort of pleasure and power in partaking in that construct.

In recent work I have been addressing how these constructs get translated in different stages of the adaptation of ‘fashions.’ How taste, even ‘bad taste’ can be celebrated in aristocratic society, but once mimicked by a different social sphere it can become kitsch and regarded as ‘aesthetic slumming.’ The concept of fashion and its association with modernity is interplay between individual imitation and differentiation. Fashion, adornment, and ornament all have vicious life cycles; newness is simultaneously associated with demise and death. Though fashion and adornment are closely related to the body, ornament can expand to architecture and environment.

I really love your performance work which I find evocative of the work of Matthew Barney and his use of the body as a vessel for exploring ideas of the human condition. In your piece, Cleaning, the situation transcends the realm of normality and speaks of a higher plane of fantastical reality where juxtaposed items like smashed glass and sweet milk come together to form metaphors about us as human beings, speaking particularly of the paradigms that surround women as having to be ‘pure’ and ‘clean’, expressed powerfully in the denouement of the piece. Tell us a bit about your thoughts behind this and what you wanted to achieve.

This was a very early piece for me that was dealing with my personal experience as a victim of date rape. This marked a turning point for me that was also inspired by a speech by Eve Ensler where she describes the verb prescribed to girls as ‘to please.’ I felt strongly that for a long time I had allowed that verb to describe my interactions with men. There is a rawness and vulnerability in this performance that is mixed with anger.

Who and what influences your work? Are there any artists you recognise as having a big impact on you and your working style?

I just adore Jim Hodges’ work. I think the wide variety of materials and mediums and the way he handles them is truly inspiring and something I look to if I am nervous about working with a new material. Matthew Barney and Alexander McQueen were huge influences in the glass headdresses and the idea of masquerade and costuming. Other influences have been the palace architecture of Catherine’s Palace in Russia. I love the over-the-topness of the patterning and the idea of excess in a space that blurs the boundaries of public and private, the domestic, and the idea of display.

You have stated that your glass headdress designs function as ‘a separation between viewer and wearer’ but that this distance is only a ‘counterfeit perfection’. How important is it for you to address ideas of distortion and fantasy in your work?

I enjoy working with things that are recognizable, but nonsensical and fantastical in their execution. I am interested in the perceptions we have in what we think we are displaying, what we actually are displaying, and how we display it. Some materials can transcend their own materiality. The glass can be seen as ice, plastic, or sugar in the headdresses. In newer work it reads as growths or caviar. Regardless of what it appears to be the fact remains that it is extremely fragile and futile. In a newer piece there is a vinyl treated chintz sofa covered in glass beads. The shiny plastic is reminiscent of plastic covered sofas as a means to preserve something nice, but it can also read almost like a piece of porcelain because of the patterning of the fabric.

What is your definition of ‘creativity’? What does it mean to be ‘creative’ in today’s world?

I believe that creativity is driven by never being satisfied with what you’ve accomplished. That there is always something that can be pushed or questioned within a material or challenged conceptually and that ending up somewhere completely different from what you intended is usually a good sign.

If you could go back in time, what advice would you give to yourself ten years ago? What have you learnt as an artist that was unexpected and what advice would you give to others?

The advice I would give myself is to never doubt your interests no matter if conceptually they might sound simplistic. There is usually something there that can be unfolded into something fairly complex.

Not being intimidated by not being technically trained in a material. Coming from an outside perspective and not knowing the right way to use a material takes away restrictions or inhibitions that might have been taught and allows a certain amount of freedom.