A conversation with KAREN MARGOLIS from Rooms 16: Superluminal

Obsessively crafted circles are the central motif to Karen Margolis’ work. The circle, sacred to many, is riddled with symbolic meaning

Obsessively crafted circles are the central motif to Karen Margolis’ work. The circle, sacred to many, is riddled with symbolic meaning. In Chinese gai tain cosmology, the circle is noted as the most perfect geometric shape and, accordingly, represents the heavens above the square earth. In Native American tradition, the medicine wheel is a symbol of life, perfection, and infinites. Even hip-hop super-group Wu-Tang Clan, 5 Percenters, praise the purity of the circle. “As God Cypher Divine, all minds one, no question,” Masta Killa recites in Visionz. In hip-hop culture, the cypher refers to freestyle rap, where interrupting another man will break the cycle. According to the 5 Percenters and their supreme mathematics, zero (or the cipher) is the completion of a circle: 360 degrees of knowledge, wisdom, and understanding.

It’s easy to see how Margolis finds boundless inspiration and energy from the round wonder. Margolis repetitively creates the shape to map out the inner dialogues of the mind. Influenced by her psychology background, she is determined to show audiences how our minds work with her art.

Rooms: Would you mind telling us a bit about yourself?

What drives me as an artist is trying to find out who I am. I feel like I exist in a fluid state within the world around me, absorbing certainties of others with no absolutes of my own. I spend a lot of time studying people's behavior and writing about it. I'm influenced by Diane Arbus' observation of "the gap between what you want people to know about you and what you can't help people knowing about you". Her work made me hyper-aware of the unconscious signals we all send out and compelled me to look below the surfaces of others as well as myself, to see the reality; so, I am focused on trying to reconcile the inner and outer me.

Rooms: Your original field of study was in psychology. Does this come to play in your artwork?

Very much so. As a child I had a lot of phobias and had become somewhat obsessed with the idea that there is another sort of energy inside of me that I could not articulate. I had seen a movie called "Forbidden Planet" that featured invisible creatures from the id and that really got my attention. After that, I found some books in the library on the inner workings of the mind and psychology became a lifelong fascination for me. In college, I focused on the brain and Experimental Psychology, which dealt with processes that underlie behavior. I didn't know what I wanted to do with psychology and ultimately dropped out of Grad School. My route has been rather circuitous, but as an artist, I wanted my work to be about mental operations, to somehow capture the mechanics of the mind. Also, it couldn't be personal and had to be about the universal. I used myself as a subject because it was easier. As an avid diarist with over 20 years of journal entries and detailed narratives of my dreams, I thought that they might be good material to begin with and created a system to chart and encode my interior monologues by translating them into colored fields of dots. These compositions on paper are visual diaries, encoded interior monologues. Working from my journals, I translate feelings into colored dots. My rules are rather loose and, depending on the writings, I use one day or a week that I transcribe into colors. I simultaneously divulge and conceal my intimate feelings.

Rooms: The circle is evidently a key component to your work. It represents the molecule, a neurotransmitter and an Enso (the sacred symbol in Zen Buddhism). The circle brings science and spirituality together in your art. Is this how you manifest all your identities and roles at once?

I look for the connective tissue between the universe and the microscopic. I have found it in the circle. It relates everything. As the most basic component in the universe, the circle can be found in all of nature as well as in religious symbols, like a halo or the Sephirot in the Kabbalah. I practice Zen Buddhism and became interested in the Enso because it represents infinity, perfection, and totality. Layering my metaphysical beliefs with chemical reactions in the brain became the basis of my work. This way I am able to reconcile the physical with the metaphysical

Rooms: Is the process of creating the circles a form of mediation, personal psychoanalysis, or trephining?

Creating circles is immensely satisfying. In meditation, you focus on your breaths and clarity somehow emerges; as thoughts pop into your head you can see that they are not real and eventually you are not held hostage by your beliefs. My process has evolved into a synthesis of meditation, stream of consciousness thinking in which I work through obsessive thoughts, and physical pain, particularly when I am burning, which I metaphorically relate to trephining. I first learned of trephination (drilling holes into people's heads) when I wrote a paper chronicling the treatment of mental illness, and the torture of it stuck with me. It was repulsive and compelling.

Rooms: You had a series where you created circles with maps. What meaning did the maps bring to your work?

I'm drawn to maps because they offer an implicit promise that they will help you find your way. In my work, the maps act as proxy for the physical self. Additionally, they frustrate expectations of any help navigating through the world. I use maps to explore arbitrary destruction and regeneration in the journey of life. After burning holes in maps, I layer them on top of each other; passages to new locations are created in places that have been lost. I invoke into my maps my philosophy that in loss something new and unexpected is found.

Rooms: Are the colors you use to represent emotions based on socialization and culture or personal instinct of how they would look?

I wanted to develop a standardized flow chart of emotions and worked with the Pantone Color System to designate a color to each emotion and coordinate families of emotions to color families (tints, saturated hues and shades). I knew from the start of this endeavor that I would not be able to have an intuitively based color chart, but, where possible, I used expected colors for emotions, like green for envy. The charts are a continual work in progress; I add new emotions to the chart as they come into my consciousness.

Rooms: By playing with the circle, you affect its perfection.

I am attracted to perfection but celebrate Wabi-sabi, the Japanese philosophy around the beauty of imperfection, aging, and deterioration. I don't think people would be very interesting without their paradoxes. I reconcile oppositions within my work, "without darkness, there can be no light".

Rooms: Your work seems extremely meticulous. Are you a perfectionist in all other aspects of your life?

I do immerse myself in details; it is just how I operate in the world, it’s not planned or thought out. That said, I am anything but a perfectionist. My mind is such a roiling sea of chaos that obsessive as I may be, nothing is perfect and all is a compromise.

ROOMS 16 presents: JULIAN LORBER

Soot accumulating on old brick buildings, paint and other media discarded by graffiti artists are not typically emblems of a burgeoning creative spirit; rather, the reminders of waste. But, artist Julian Lorber has a peculiar eye: he is also drawn to polluted skies, automotive coats, and cosmetics products. Artifacts of an over consuming society. In Lorber’s current series, he uses archival tape to create defiled landscapes.

Rooms: What does light mean to your practice?

In the work that I’ve been involved with for the past three years, I’ve used light to bring out illusions and visual hierarchies in the painted pieces. The work is painted so that depending on the type of light and the direction of the source, the artwork can have the faux-natural light of a particular time of the day. Part of the inspiration of these paintings was looking at the soot built-up on the edges of bricks and other architecture under certain light and thinking to myself, ‘that would be an interesting way to paint.’

The tape marks and application of paint in your work create an impressionistic quality. Was this intentional?

Mostly yes, and I’ve been resistant to saying my artwork is entirely abstracted. My work is mostly landscape or something objective and I do paint for a certain type of light, in a range of colors that might seem fugitive, for example, when I paint the shadows or soot lines with bright mixed colors. Now that I’m really thinking about it, some of these fugitive color combinations have been something that digital cameras can’t seem to capture. This might alienate viewers that look at documentation of art on the web, but the impressionist colours and styles had the same effect on their audience. Of course, seeing my artwork in person is profoundly better. It’s always interesting when viewers assume they are digitally printed at first, because of my painting methods, and then realize they are physically textured and painted.

In your latest series, as featured in ROOMS 16 Superluminal, you build your canvas with archival tape prior to painting. Has building up your canvas always been a part of your process?

Not always. I used to layer using just the drawing and paint to create tension and dialogue between the layers, but still retaining a surface focus. I was interested in the drawing under the paintings and what was underneath the exteriors presented around us. I presented these artworks in a show called the Real Illusions in Painting but I really felt there was something physically missing that I wanted to include. So I started cutting and layering with different media and eventually used archival tape.

Can you tell us a little bit more about the layers you create?

The physical layers are my way of creating my own surface or creating my own architecture on the surface. Falling bricks, bandages, or just the act of covering up with tape allowed me to make statements about surface and make walls that I could paint on. The physical tape also allowed me to build up colours on the edges in the same way soot accumulates on bricks and other surfaces, which was something I was observing and thought was interesting.

Your work draws from graffiti, urban, and man-made spaces, but also retains colors from natural properties. Color is also restrained on each canvas.

I enjoy color sensuality and the way it elicits an emotional response from viewers. The concepts in my work about the environment complement this response and create the dialogue that I’m interested in having. The dialogue being that one is looking at something that can be considered attractive, like a sunset or layers of paint on architecture, but at the same time there are positive and negative externalities present or being presented.

You control substances in order to create architecture of pollution. Is environmentalism important to what you do?

I care enough about the environment that I’ve dedicated years, and much of my work so far, to conveying ideas through my artwork about the subject. I think it comes down to intentions. Although I’m using materials that are harmful to produce, the fact is almost everything is: if you take an object like a brick, which was a good idea and intention, it just depends on what you do with it, despite the fact that if you go back far enough, it was probably made from Saudi, American or Chinese oil. The point is how you use those resources and what your intentions are.

Does living in Brooklyn affect how you look at decay and progress?

To a degree, yes. I’ve titled the project I’ve been involved with for the past few years Externalities because it is from observing the positive and negative occurrences from progress. Brooklyn is very industry-heavy, but because of people living so close to it, you can see its effects quickly, and also see the proactive response from lawmakers and scientists. Seeing street or outdoor/public art leap forward due to popularity has been another interesting experience. With that said, seeing outside of my town helps to keep perspective and to add nuances to the story I’m trying to tell. I often look at LA, China, and now Houston.

What sci-fi story does your work tell?

It’s dark humor. A story that’s about living with, and relying on, a system that is harming us. We have to look at this story in a type of light which is beautiful, and that pleases us so we can focus, all while knowing, and denying the truth, that we are not only part of, but also responsible for, this coexistence.

Check out Julian Lorber’s work in our current issue ROOMS 16 Superluminal

ROOMS 16 presents: LUCY LUSCOMBE

The Filmmaker Method

Lucy Luscombe's career is like cracking open a bottle of Moët et Chandon with the toughest cork, it felt stuck at first but once it's open, it just keeps gushing out in all her stormy glory, drenching her in a sea of projects that she comfortably swims though. Vogue, Channel 4, Nike and many other organizations are just a few of her high profile clients. Since the interview she's already released another music video for artist Juce! for her single “6th floor”, in which the banality of London lives of a few individuals are amplified and celebrated, in similar fashion to some of her other works including Tiny Ruins' video “Carriages” which features Channel 4 actor from “My Mad Fat Diary” Nico Mirallegro. The sentiment is very much reflexive in her works, it's invoked rather than shown or told. ROOMS exclusive interview with the 28-year-old Lucy Luscombe can be found in ROOMS 16 Superluminal

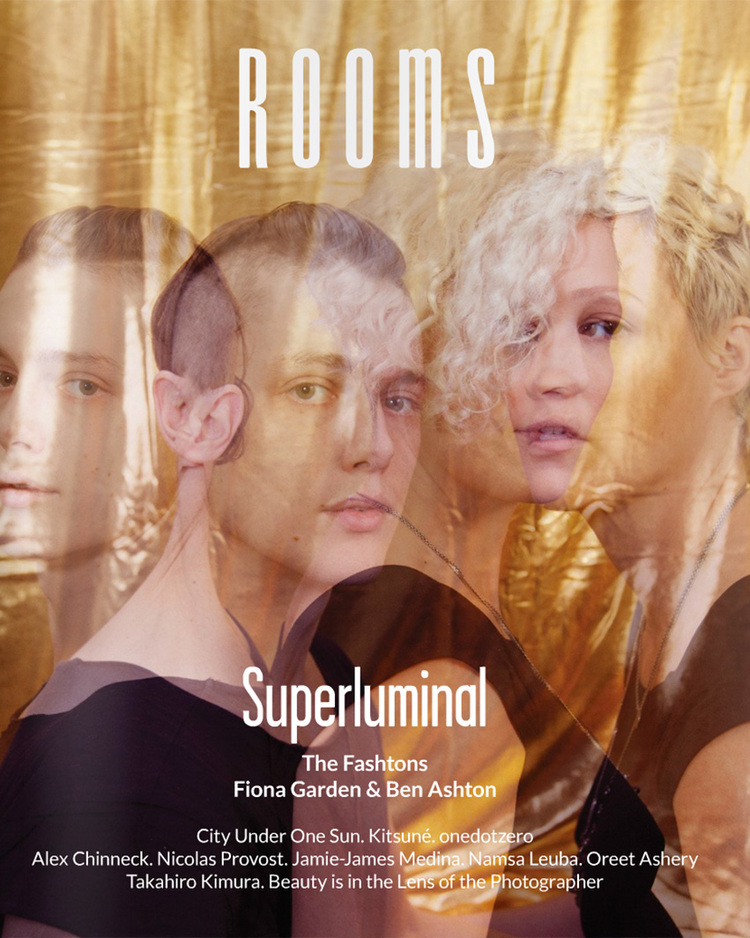

Presenting ROOMS 16: SUPERLUMINAL

“This is how it all begins: from blinding darkness enters light; soft, beautiful, expanding, violent, maddening, defiant”

“This is how it all begins: from blinding darkness enters light; soft, beautiful, expanding, violent, maddening, defiant”

ROOMS 16 is all about light, offering an explosion of colour, yet meditating the significance of contrast, of darkness. The darkness behind the light, which serves as a technical tool, an inception of creativity. Together with the artists who make up this issue we seek to illuminate what happens when we stop thinking of light and darkness as binaries, but rather as parts of the same force. The force that drives us to create, destroy and recreate. As featured photographer Ryan Harding points out, one must accept the necessity of scrapping things in order to reinvent. To improve. To excel.

Following this year’s Art Basel – Miami Beach, ROOMS 16 muses the creative processes and emotional influences of three Miami-based artists as Autumn Casey, Farley Aguilar and Bhakti Baxter consider the impact of the Sun City on their work. While the works of contemporary artists often exist by an illusion of lighting and composition, the illusion is accepted as an ancient and indispensable artistic extrication. Further, a focus on light in composition is evident in Pawel Nolbert’s works as he discusses the effect colour has on perception and visual impact. We also talk “lighting” with award-winning photographer Jamie-James Medina, whose diverse portfolio includes dramatic and characterful portraits of Mercury-prize nominee FKA Twigs.

ROOMS 16 explores the realms of digital artistic expression, introducing the work of two extraordinary digital artists, Robert Bell and Andreas Nicolas Fischer. Their compositions are eruptions of light and yet contain within them sinister elements

adding to the intensity of the visual experience. Featured also is onedotzero, a company responsible for creating astonishing digital sensory arts events, and Eduardo Gomes, who uses 3D computer graphics to implement and demonstrate visual artwork.

Without borders or boundaries, Alex Chinneck creates large-scale surrealist illusions. He describes the making of playful public art, the obligation for cultural experiences to be valuable and also the advantage of controlling your art, beginning to end. With The Fashtons, we ponder photo-realism in visual projects for music and fashion and the consonance brought by two separate, yet intertwined and transmittable, artistic modes of expression.

ROOMS 16 cogitates the blurring of liminal spaces, the creation of complex art. The result is art, which breaks boundaries. Art as light and darkness, simultaneously. Art, which is faster than light itself. Art, which is superluminal.