The story of painting rascal Ide André

“Everyone can say what they want, but I do hope that my work comes across as fresh, dirty, firm, crispy, dirty, clean, fast, strong, smooth, messy, sleek and of course cocky.”

“Everyone can say what they want, but I do hope that my work comes across as fresh, dirty, firm, crispy, dirty, clean, fast, strong, smooth, messy, sleek and of course cocky.” – Ide André

Somewhere between the concrete walls of the Institute of the Arts in Arnhem, a talented kid with a big mouth and an urge to paint was bound to challenge perspectives. Years later, he found himself rumbling in his atelier, experimenting with ideas and creating things out of chaotic settings. With a determined attitude and an open mind, he managed to turn everything into a form of art. Some people liked his work, some people questioned it; either way it got attention. Right now, he’s working on several projects all exploring the relationship between painting and everyday life with the carpet (yes, the carpet, I told you this guy can turn anything into art piece) as main subject. His work is a reflection of his personality: bold, impulsive, fun and with a fair amount of attitude. He however likes to use a couple more words when describing his own work. This is the short version of his biography, the end of my version of his story. If you prefer a more authentic one here’s the story in the artist’s words:

I once saw a show of Elsworth Kelly when I was a child. The enormous series of two-toned monograms clearly made a big impression on me. I remember staring with my mouth wide open at the big coloured surfaces. I’m not that much of a romantic soul to say that it all started right there, but it did leave an impact on me. I actually developed my love for painting at ArtEZ. I started out working with installation art and printing techniques, but I was always drawn to the work of contemporary, mostly abstract painters, until I actually became fascinated about my fascination with abstract painting. Because, let’s be honest here, sometimes it seems quite bizarre to worry about some splotches of colour on a canvas. Even though painting has been declared dead many times over, loads of people carry on working with this medium no matter what; from a headstrong choice, commitment or just because they can’t help it. I am clearly one of those people, and that fact still manages to fascinate me.

At ArtEZ you talk so much to your fellow students, teachers and guest artists, little by little you kind of construct your own vision on art. And that’s a good thing! All this time you get bombarded with numerous opinions, ideas and assignments, some of them (as stubborn as we are) that seemed useless to us and weren’t easily put on top of our to-do-list. Until there is that moment you realise that you have to filter everything and twist and turn it in your own way. Then there is that epiphany moment. That moment you realize you can actually make everything your own. I think that’s the most important thing I’ve learned during University: giving everything your own twist and constantly questioning what you are doing, subsequently always struggling a little bit but still continue until the end. Like an everyday routine.

I’m not going to enounce myself about the definition of art. That would be the same thing as wondering what great music is or good food. I think it’s something everyone can determine for themselves. I do think it is interesting to ask myself how an artwork can function and what it can evoke. There is this exciting paradoxical element within art. On the one hand we pretend that art should be something that belongs to humanity, something that is from the people, for the people; on the other hand is the fact that art has its own world, its own domain where it can live safely, on its own autonomous rules, and it doesn’t have to be bothered by this cold, always speculating world. There are pros and cons about both sides, and I think it’s impossible to make a work of art that solely belongs to one of the two worlds. As Jan Verwoert, Dutch art critic and writer, words it: “Art as a cellophane curtain”. Without getting too much into it (otherwise I’m afraid I’ll never finish this story), there is this see-through curtain between the two worlds. The artist is looking at the outside world through his work, and the outside world looks at the artist through his work. That’s how I see art and how I approach it.

My work often comes about in various places, with my studio as a start and end point. I buy my fabric at the market and from there the creative process really starts. I print on them, light fireworks on them with my friends, or sew them together with my mother at the kitchen table in my childhood home. I try to treat all these actions as painting related actions. Like a runner that goes to the running track on his bike; we could ask ourselves: is he already exercising running? On an average atelier day, I toil with my stressed and unstressed fabrics, chaotically studded around the room. Usually I don’t have a fixed plan. My process is semi-impulsive and comes from an urge. Often this causes little and mostly unforeseen mistakes, these ‘mistakes’ often prove to be an asset in the next project.

As for the future, (Lucky for me) I don’t own a crystal ball, so I wouldn’t dare to make predictions. And quite frankly I wouldn’t want to know. Young collectives, initiatives and galleries keep popping up and I think we continue to grow more and more self-sufficient. Of course there is that itch of our generation to always learn more, do more; an urge that I believe will never disappear, also not within myself. I will stubbornly continue to work on the things I believe in. Not because it offers me some sort of security (most of the time it’s the opposite) but because I just can’t help it.

Ilse Moelands : A touch of heart, a mark on paper

Dutch illustrator Ilse Moelands’ drawings awaken emotions in an utterly beautiful way. Freshly graduated, she’s on the verge of publishing a book and continues to translate her fascination for the Far North into stunning drawings.

Dutch illustrator Ilse Moelands’ drawings awaken emotions in an utterly beautiful way. Freshly graduated, she’s on the verge of publishing a book and continues to translate her fascination for the Far North into stunning drawings.

Ilse Moelands: I’ve always doubted about my future and thus I had a lot of difficulties choosing the right study; would I become a doctor, an artist? I have always loved fashion and it’s influence on our culture and identity. To me fashion is about people and their characteristics and for a while I wanted to continue in that direction, ignoring the fact that I can’t sew at all. I thought I’d give it a go and ended up enjoying the drawing part the most. I wanted to draw all the time, so I decided to change studies and go for Illustration Design at ArtEZ. I like the directness of drawing and printing. Sewing and designing fashion is a much slower process.

Tell me something about your drawing process.

Often my urge to draw awakens when I am fascinated or frustrated. Then my ideas flow out of me on paper. I like to draw when I am alone, because I really have to be focused and concentrated.

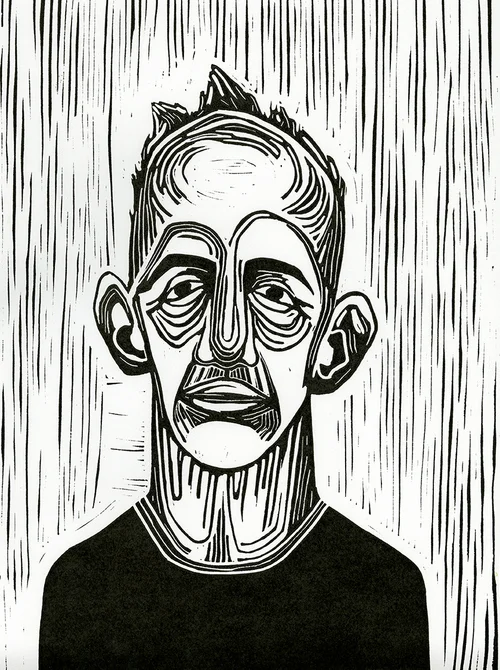

You use a lot of older techniques such as thinner press and lino press, this is quite unusual in our digital era. Why these techniques and how did you come in touch with them?

I like to start with something physical, so I can smell the material; I want to have paint and ink on my hands. I just love the imperfection. It’s not that I don’t like digital work. I think there are a lot of possibilities working digital, but it’s not my cup of tea. At the art academy we had a really nice printing workshop. During my last year I spent as much time as possible in the workshop experimenting with all kinds of techniques and became intrigued with the older ones.

Your work instigates deep emotions, from the love for family to shame and loneliness. Are these feelings you experienced yourself when working on your drawings?

Yes. I always start with a very strong emotion, because it’s the only way I can make satisfying images. I think the world is a weird, crazy place and making art is my way to deal with that. It’s like therapy. But I try to make my work for other people as well. Emotions are a good starting point, but I always try to twist it in a way, so a lot of people can relate to my stories and images.

Where do your ideas come from and when is an idea good enough to execute?

People and their stories inspire me a lot. I am pretty hard on myself, so things aren’t good enough for me very easily. But I am still learning to let go of this perfection, and sometimes I overthink things and I stop myself from making art. But I always try to remember that small ideas can lead to big beautiful projects.

Talk to me about your fascination with the Far North, what is it that attracts you to it and inspires you to create illustrations?

I have worked and lived amidst the snow, polar bears, seals, and Inuit, I grew a fascination with the extreme living conditions those people have to deal with and how they remain a balance of sensitivity and strength. The hard, isolated existence and the respectful way these people treat nature provide the basis for the graphic story I’ve created for my graduation. The Inuit are very proud people however I can’t help but feel they are a bit lost, uprooted from their original culture as times have changed so much there. This idea had an immense impact on me and on my work. I went there with a lot of questions, but I came back with even more. I would love to go back there one day and maybe live even more primitively and remotely.

You went to Upernavik, Greenland for half a year. How did you end up there and what is the most important thing you’ve learnt?

A year ago I applied for the Artist in Residency Program in the Upernavik Museum. After waiting impatiently for a very long time, I was so happy when I received a letter saying they had chosen me to go there. The most important thing I learnt during my stay in Greenland is to be more calm and relaxed. Nature dictates the rhythm of life, so you either go with the flow or feel very miserable. I had to let go.

You're currently working on a book with Julia Dobber; tell me something about this project?

Next to the Greenland project, I needed something else so that when I was stuck with one project, I could escape into the other. I met Julia through a mutual friend and I instantly fell in love with her stories. Her work is about people who get through things, but nobody knows exactly what. For my graduation we compile six stories and complimenting drawings. Finishing them we both felt that there needed to be more, so our plan is to make twelve in total. I can’t wait to continue our exciting project and have the finished product in front of me.

Is there a particular artist you would love to work with?

Several. I really like the work of photographer Jeroen Toirkens. He’s a Dutch documentary photographer who followed several Nomadic cultures around the world for years. Also fashion collective ‘Das leben am Haverkamp’, which is founded by some of my old fashion classmates. I really like what they are doing and they inspire me to carry on. Maybe one day we can do a project together.

What is your plan for the future now that you have graduated?

I always hate this question... It feels very definite to talk about the future. I can only dream about it. I would love to have a little workshop with all kinds of presses so I can make special prints and books. I hope I can do more residencies and visit other countries. I went to Myanmar a few years ago and I really want to go there again to start a new project. But there are a lot of other things I dream about, for instance more collaborations like the one with Julia Dobber. I really like dreaming..

We meet fabric illusionist Yvette Peek

The ArtEZ design alumni blew everyone away with her graduation collection, sending illusional masterpieces down the catwalk. Check out the interview.

All keep track of upcoming designer Yvette Peek. The ArtEZ design alumni blew everyone away with her graduation collection, sending illusional masterpieces down the catwalk. As curious as we are, we had a talk with her about the story behind her first collection, her admiration for strong women with non-conforming elegance and being the assistant designer of Sharon Wauchob.

What made you realize you wanted to be a designer?

My biggest source of inspiration is my grandmother. When I was a little girl, she taught me how to sew. That led to her teaching me embroidery techniques and pattern making. We even stitched my first designs together.

What do you think are your biggest assets as a designer?

As a designer I challenge myself to find the unexpected in materials and textiles and I made that into my greatest strength. When I design clothing I always have a strong woman in mind, with non-conforming elegance and a luxurious approach to colour and fabric. My graduation collection is based on the insomnia drawings of Louise Bourgeois. One of the strongest and most inspiring women I have ever known.

Before you started with the collection, did you already know the outcome of the design concept?

I went to the exhibition of Bill Viola during my internship in Paris. This was one of the most exhilarating exhibitions I have ever seen. My eye caught on of his illusional art pieces ‘Veiling’ of Bill Viola. In a dark space, an unfocussed film of a man is projected through 10 translucent sheets of fabric, growing paler and larger towards the centre. Two projectors at opposite ends of the space face each other and project images into the layers of material. I became fixated on this video installation. And from that moment on I knew that I wanted to recreate that illusional effect with different kind of layers fabric in my collection. The elements of shape-shifting developed later on, during my drape sessions. After a few drape sessions I came to the idea that my collection had to represents the brain that is experiencing insomnia, and that’s where the insomnia drawings came in.

You interpreted insomnia with fabrics where Louise Bourgeois did the same thing with pencil. Why is it that your collection exists of tints of black, grey and white, while bourgeois’ work consists of colour?

The type of woman I made this collection for is elegant, unpredictable and psychotic. I have used darker tones to create that psychotic vibe. And the best way to create an unpredictable illusion through different layers is to use tints of black and grey.

Can you tell us a bit more about the design process behind the collection?

Quality of fabric and craftsmanship are my most important values when designing. Therefore I won’t be looking at the clock when working on my designs. My collection consists of a lot of different crafts that have to be meticulously conducted. One look required an embroidered top that consists of 460 small pieces of springs that I have formed in circles, and those springs and beads are all embroidered by hand. This took my approximately three weeks. The two last looks in my collection consist of 22 meters of tulle per outfit, all hand-printed with markers, and 4.5 meters of printed plastic. From of all the time I spent working on my collection, those looks were the ones that took up the most time.

You're working as an assistant designer for Sharon Wauchob now. How did that happen and what do you admire about her work?

I worked as an intern for Sharon Wauchob two years ago. During my internship I was assigned as assistant textile/embroideries designer. This was one of the best learning experiences I had so far as Sharon gave me a lot of opportunities to develop myself. After my internship I went back to school for my final year but I stayed in contact with her and I always came back to Paris to help the team during Paris Fashion Week. Sharon is a consistently talented designer who creates thoughtfully engineered garments. I admire her strong detail-focused aesthetic. The way she uses traditional techniques and delicate fabrics in her collection inspires me.

How do you see your career developing from now on?

I would like to gain more experience within the field of design. I hope to get the opportunity to learn a lot from Sharon Wauchob over the next years. It would also be interesting to develop myself within another creative luxury brand with a focus on textiles, but we should not jump to conclusions. You never know what happens and I am looking forward to every new opportunity!

Time-lapse | An interview with Jeffry Spekenbrink

Jeffry Spekenbrink is a photographer, filmmaker and visual image artist whose works are the result of a very long and dedicated process involving his camera and the unremitting power of earth’s multifarious landscapes.

Jeffry Spekenbrink is a photographer, filmmaker and visual image artist whose works are the result of a very long and dedicated process involving his camera and the unremitting power of earth’s multifarious landscapes. Using his photography to create time-scapes, Jeffry’s works transform the everyday into an otherworldly representation of stunning visuals, perspectives and pure cinematography, often captured in the space of a few minutes.

In 2014, Jeffry graduated from the ArtEZ Institute of the Arts in Enschede and was a finalist in the TENT Academy’s Film Awards for his hugely successful time-lapse film, Part of the Empire/Plague. His video presented a six-minute compilation of the many highlights captured on his journey that stretched between the uniquely desolate environs of Iceland to the densely populated French capital of Paris and with it, the realisation of a growing population living in social isolation.

Jeffry’s accompanying music adds an extra exciting, slightly unnerving feel to the film and the sheer spectacle of the entire video is incredible to behold. I caught up with the man behind the lens to find out more about his journey.

How did everything begin for you? What inspired you to start making time-lapse videos?

I bought my first DSLR in 2010. Shortly after I saw a short time-lapse video from the northern lights shot somewhere in Norway. I was really touched by this phenomenon, but also by the way it was shot. It gave me a very calm and serene feeling and I realised that, although it looked very surreal, this was a real life phenomenon, captured by just a camera. From that moment on I began to experiment with my own camera as often as I could.

With every meteorological phenomenon that I was able to capture around my house, I began to wonder what it would look like in a time-lapse video. Just like analogue photography, you could never tell what the actual footage would look like until the process of digital developing… making a video out of the few hundred pictures that you take.

A time-lapse video can also create a very different perspective…

I love the perspective of the time-lapse medium… it’s almost as if you are looking at the world from another sense of time. It’s the perfect medium to let people realise what their civilisation looks like from an outsider’s perspective. I didn't realise this until I started shooting cities. This changed the composition of a wide-angle view to a shot of the people from above. I wanted to give the people a look at our world from a slightly different perspective.

A lot of your shots capture scenes without people…

I have always had some kind of curiosity for desolate places. I lived my life in the countryside in the east of the Netherlands, but there weren’t really any desolate places here, I was always wondering how it would feel to be in a place where it was just you and nature. I liked the nights because they were quiet and nobody was ever around to ruin the shot.

What was the inspiration behind Part of the Empire/Plague? Were there any main themes that you tried to incorporate within your images?

At first I just wanted to capture the feeling of serenity that I got from watching night skies and empty landscapes, but I also wanted to add a subtle storyline. I started writing ideas on paper for a short film. That's how I came up with the idea to contrast an empty landscape with a big city. I had lots of ideas but no budget, so I had to make choices… my priority was to show the biggest contrast possible.

You must have travelled quite a bit for this project…

I didn't have much of a budget, so I saved and made a shooting list with all the shots I needed. My first priority was to look for desolate places. The Northern lights was first on the list, which I knew would be difficult to capture. So after doing some research, it came down to Iceland in April.

“In April, Jeffry took a three-week trip with his car and 1.5-meter long slider to Seyðisfjörður in Iceland and spent fourteen consecutive days shooting time-lapses. The results were mind-blowing.”

Had you visited all of these places before?

I had never been to Iceland. For the cities, I had been to Rotterdam and Paris before but not to the places I needed to take the shots from. So again I had to do some research before I went.

Why Iceland?

Iceland has a very unique and various landscape with volcanic activity, glaciers, moving icebergs… its sea with black beaches. In the summertime it doesn't get dark in Iceland… that means there are no Northern lights to see and in the wintertime it stays dark, so not ideal for landscapes. That's why I wanted to go in April, the last month that you can see the northern lights, and experience Iceland with a day and a night.

After Iceland I needed city footage. I went to stay with a friend in Rotterdam to practice and shoot footage for the film but was looking for a bigger city like Paris or Berlin to shoot from a higher perspective.

Is digital manipulation a strong element of your work?

The film consists of 12.406 21-megapixel images from the 23.807 pictures shot in total. Because it is made out of 14 bits RAW-images you get the possibility to pull great details and beautiful colors out of the image. I also used filters whilst shooting to level the contrast between the sky and the ground - this is how you get more details in the clouds.

In some shots I removed smaller elements such as dust and birds… these were distracting because they were moving too fast. I wanted the viewer to focus on the slow movements that become visible due to the acceleration of time, like the movement of the clouds and the water.

Digital manipulation is an important element, but it has to remain the reality. With every shot, I experienced the environment and tried my best to express the feelings I had at the particular place through the image. I did that separately with every shot of the film.

There’s been a lot of interest recently in nature and the man-made. Do you think that your work reflects this through the contrast of rural and urban landscapes?

I think so, yes. It was my meaning to show people the contrast between the rural and urban from an outsider’s perspective, in combination with my view of the places.

The whole experience of traveling has been very important for the end result. During the city trips I experienced something really different to that in Iceland. It takes up to a few hours to take one time-lapse shot so during that time I was able to observe my surroundings very well.

Whilst I was looking around in the big cities I felt proud to be a part of a successful society. At the same time I felt a part of a huge growing population in which nobody really cares about the individual. I experienced the same in Iceland… I’d expected to find a lot of pristine nature, which we found, but it turned out to be pretty touristy.

Can you tell me about some of your favourite photographs captured within this time-lapse?

Technically, the first shot from the Eiffel Tower in Paris is my favourite, because that was number one on the list for Paris and I was quite happy with the end result, despite the challenges. I chose the Eiffel Tower because it has a fence at the top instead of windows. Taking pictures through the window of a high building brings more complications like reflections and limitations in focus length. The movement of the top of the tower caused by the win, for example. I wanted to take all of my shots at night which meant that I needed to use as much wide angles as possible and keep the shutter speed as short as possible to avoid blurry images.

Emotionally, both the Northern lights and the church are my favourites. In the two weeks that we were in Iceland, there was only one clear night when we the Northern lights could be seen so I was quite lucky to have experienced that. I drove my car up to the highest mountain in the area and aimed both of my camera’s at the sky. I go my own lightshow, which was stunning. And because I had to use exposures of 8 and 10 seconds, I had to stay there for 2.5 hours for less than 40 seconds of video, so I watched it from beginning to end. For me this was a very special moment, all alone on a mountain with a personal lightshow brought to me by nature.

After that, the northern lights only showed up once, barely visible with the naked eye, which became the shot with the full moon.

“For me this was a very special moment, all alone on a mountain with a personal lightshow brought to me by nature.”

How do you capture your chosen landscapes? What is the process?

I was well prepared before the traveling. I had already made a shooting list and decided the composition. It's always different when you get there but most of the time I stuck to the plan… that worked out pretty well, especially in the cities. For Iceland we planned the route. I had all of the spots marked on the map but I could never tell when I would see that thing on the list. The best shots were the spontaneous ones, and that's most of them!

Were there any challenges you faced along the way? Any freak weather conditions?!

Technically there were a few struggles like dust, but mainly the cold… harsh winds all of the time, blizzard, roads blocked with huge piles of snow… The shot with the wavy clouds under the orange sky, for example. I had wanted to shoot it from the top of the highest mountain on the map but that didn’t work out because of the weather conditions. I saw these clouds when we were in a village and they were pretty far away but I just had to make that shot, so I used a telephoto lens… slightly different than expected but in the end everything went well, we were pretty lucky I guess…

Timing is obviously a huge factor within your works... How long does a time lapse usually take to photograph at one specific location? The Northern Lights, for example, you capture them so beautifully!

In the daylight the interval between the pictures can be very short, but I used intervals of 4-6 seconds most of the time depending on how fast the clouds were moving. In the cities I chose to shoot everything at night. I think cities show their true beauty at night, when you see only the things that matter and all the movements become visible in lights.

With the Northern lights it was really dark so I had to take exposures of 8-10 seconds with a high ISO. For 10 seconds of video in 30 frames per second you need 300 pictures and the actual time to take the shot varies between 20 and 75 minutes.

And I understand you composed the music by yourself? (which is stunning!) What was the process? The film’s sense of discovery and wonderment is just incredible.

In my opinion music is a piece of art on its self, that's why I didn't want to use the music of another artist. Music is very important for guiding the viewer through the images. To me the choice of music is responsible for half of the emotion you are trying to express through the film. Because the whole film is a very personal work to me, I couldn't think of another way than to make my own music for it.

I play guitar and I also took it with me to Iceland. There were a lot of moments when I could play the guitar and so I began to come up with the basics of a song for the film. The guitar at the beginning of the song was recorded at home and I went on from there digitally, using the same chords for the other instruments.

I then categorised the shots and adjusted the music to that. Basically I worked the other way around… the images were most important and the music had to bend and support the images. That’s a really satisfying thing to do because you’re not able to do so with the already existing music.

Is music making something you intend to pursue?

Yes, at the moment I am quite busy recording my own guitar playing and singing to improve the quality of my music for my next work.

All images © Jeffry Spekenbrink