Hayden Kays on The Top Ten

Hayden is a visual artist who splices together witty wordplay with carefully chosen found photographs, often subverting the meaning of both.

Hayden is a visual artist who splices together witty wordplay with carefully chosen found photographs, often subverting the meaning of both. Not one to be tied to just one medium, Hayden also works with sculpture, drawing, and printmaking.

His new show ‘The Top Ten’ at Cob Galley Camden, is a collection of the ten most popular artworks from his successful typewriter series, and will tour around the world this summer.

BM – Why did you decide to re-curate the typewriter series into this new show?

HK – I was getting loads of enquiries about the same works again and again in ‘The Hot One Hundred’ and not wanting to keep producing the A4 versions it seemed logical to produce larger print editions of the most popular and some of my personal favorites.

BM – Your work masks a poignant message under a veil of comedy. Why do you think this contrast is necessary to deliver your message?

HK – I don’t think it’s crucial. I just fucking love laughing. I have an extreme sense of humour; it’s virtually a disability. I find EVERYTHING funny. I wish I had control over it, I’m envious of people who can control laughter but I think they are few and far between, this is another reason I love to use humour in my work – laughter is convulsive, you don’t decide what to laugh at. You laugh, then you worry about whether or not you should have later.

BM – You identify yourself as a ‘Pop Artist’, when most pop art is vacuous. You seem to have a deeper ideology than just making money. Why do you identify with Pop Art so much?

HK – I think I’m becoming more and more of a ‘Pop Artist’ in the sense that my work is becoming more and more popular. Popularity is important to me. I want my work to be liked. Find me an artist that doesn’t and I’ll show you a liar.

BM – Do you believe in a high art/ low art distinction, and where would you place yourself?

HK – I believe it’s either Art or it isn’t Art, and unfortunately I see ‘it isn’t Art’ by far too many people that call themselves artists.

BM – Why do you think that you often get grouped amongst the ‘street artists’, despite doing very little work outside?

HK – Because people don’t know where to put me. We are all obsessed with compartmentalising everything, everyone, it helps us attempt to understand these terrifying surroundings.

BM – As a lot of your work is humorous, does that mean that it is fun to make, or can it be stressful at times?

HK – There is a common misconception that artists are just having a great time splashing paint around a lofty studio, smoking roll-ups and shagging loads of girls. I just smoke the roll-ups.

BM – How much of what you do is hyperbole?

HK – You can take my work however you like, just as long as you take it.

BM – Sometimes it’s hard to tell who it is you’re making fun of in your work, the subject of the piece or the viewer, or even society as a whole, is this intentional?

HK – I don’t want to make work that's instantly or easily resolved. Questions that you answer, you tend to move on and away from. I want you to keep coming back to me.

BM – A lot of your work is text and found imagery based, how do you collate your ideas. Do you sketch or is your sketchbook full of lists?

HK – I have piles and piles of sketchbooks full of ideas. I hope when I’m dead they’ll slowly all come to life as I’ll never find the time to make them all exist in my lifetime.

BM – Do you believe an artist should have to explain their work, or is it the public’s role to decipher it?

HK- I don’t think art should have to be explained. It should be simple. Ask yourself do I like this? If you do, you do, if you don’t you don’t. You shouldn’t make it much harder.

The Top Ten opens on the 2nd of April 2015 at Cob Gallery Camden | Hayden Kays

In Contemporary Conversation with ALICE WOODS

With a portfolio that is both aesthetically alluring and rooted heavily in social consciousness, it’s no secret that London-based artist Alice Woods does not shy away from bold materials, messages, and mediums. Hoping to “address our economic knowledge deficit and elucidate the relationships between economic decision making, cultural preferences and political transitions”, Alice uses in-depth research and meticulous metaphors to illustrate contemporary – and often controversial – issues. We chatted with the artist to find out more about her social stance, artistic process, and exciting plans.

Your body of work is clearly very diverse, spanning 3D sculpture, installation, video, and conceptual pieces. What is your artistic background?

My background is actually in music, and before art school I attended a music school for 5 years as part of my secondary education. This was an incredible experience, and one that taught me a lot about working under pressure and how to learn your craft. Although music will always be a massive part of my life, the particular nuances of the type of classical music I was studying are quite narrow and demand near perfection from the performer. In the end I think I turned to art as a sort of antidote to this way of working, and somewhere I could be much freer with my ideas and interpretations.

How did you come to work with so many different mediums?

I think it began right from my first experiences in art education. I was enrolled in the foundation course at Central Saint Martins and there I specialized in ‘Contextual Practice’ which focused on research led enquires. Because of this, the idea always came first and medium was determined by whatever was a natural fit. I have always continued this approach and try to not pigeon hole myself within any particular medium as a way of keeping my thoughts as free as possible, and to ensure I don’t place any preconceived limitations on my practice.

You note that, as an artist, you explore “the implications of financial & economic power structures”. With motifs spanning government surveillance, corruption within the stock market, and the proliferation of technology, this focus is extremely apparent in your work. What sparked this interest?

A desire to understand and reveal the workings of the financial sector was sparked by the onset of the 2008 global financial crisis, and through my experiences of growing up in North East England where the effects of the recession have been felt in full force. Amidst the rise of the Occupy Movement I spent time down at the encampment by St Paul’s and this solidified my interest in the implications of extreme income inequalities and how neoliberal policies filter down to the public whose interests are often in a very different arena from those in Westminster.

Did you explore these themes in your early work, too?

My early work was more concerned with value and worth, and then when the recession hit and Occupy gathered pace, these initial themes started to focus more on the nitty gritty of what we ascribe worth to in Western society and the implications that our particular form of capitalism has on communities and individuals.

While such concepts are rooted heavily in issues related to society as a whole, you also comment on the role of the individual with pieces like Sally (The Watcher) and the Al Capone experiment from your Google Trends series. I find your exploration of the relationship between society and the individuals that comprise it so fascinating. Can you touch on it a bit further?

I suppose I am interested in people’s perceptions of society vs. the individual. It is often quipped that we live in a very individualistic society, a sort of dog-eat-dog world where everyone is out for their own gains. But if you look around I don’t think this is actually the case; things like Occupy couldn’t happen if community and safeguarding opportunities for future generations didn’t matter to people. Maybe I’m just an optimist but I believe the ordinary person on the street will do the right thing if they have time to stop and think, often though modern life puts us under so many pressures (namely paying off debt of one form or another) that there isn’t time to really pause and take a moment to breathe.

Similarly, on your blog, you reference the relationship between the “powerful and the powerless.” Who do you see as powerful, and who do you see as powerless, and how is this conveyed in your work?

Within my work I try to take an objective outlook so I don’t explicitly acknowledge my personal opinions on who I think is powerful or not, but try to let the audience make up their own minds by introducing these forces within the fabric of the work. As much as I am interested in when power goes wrong I am also interested in when it works for the good of humanity. So exploring when power is used for inspirational leadership, for example, is as important to me as exposing elites who manipulate the system for their own gains.

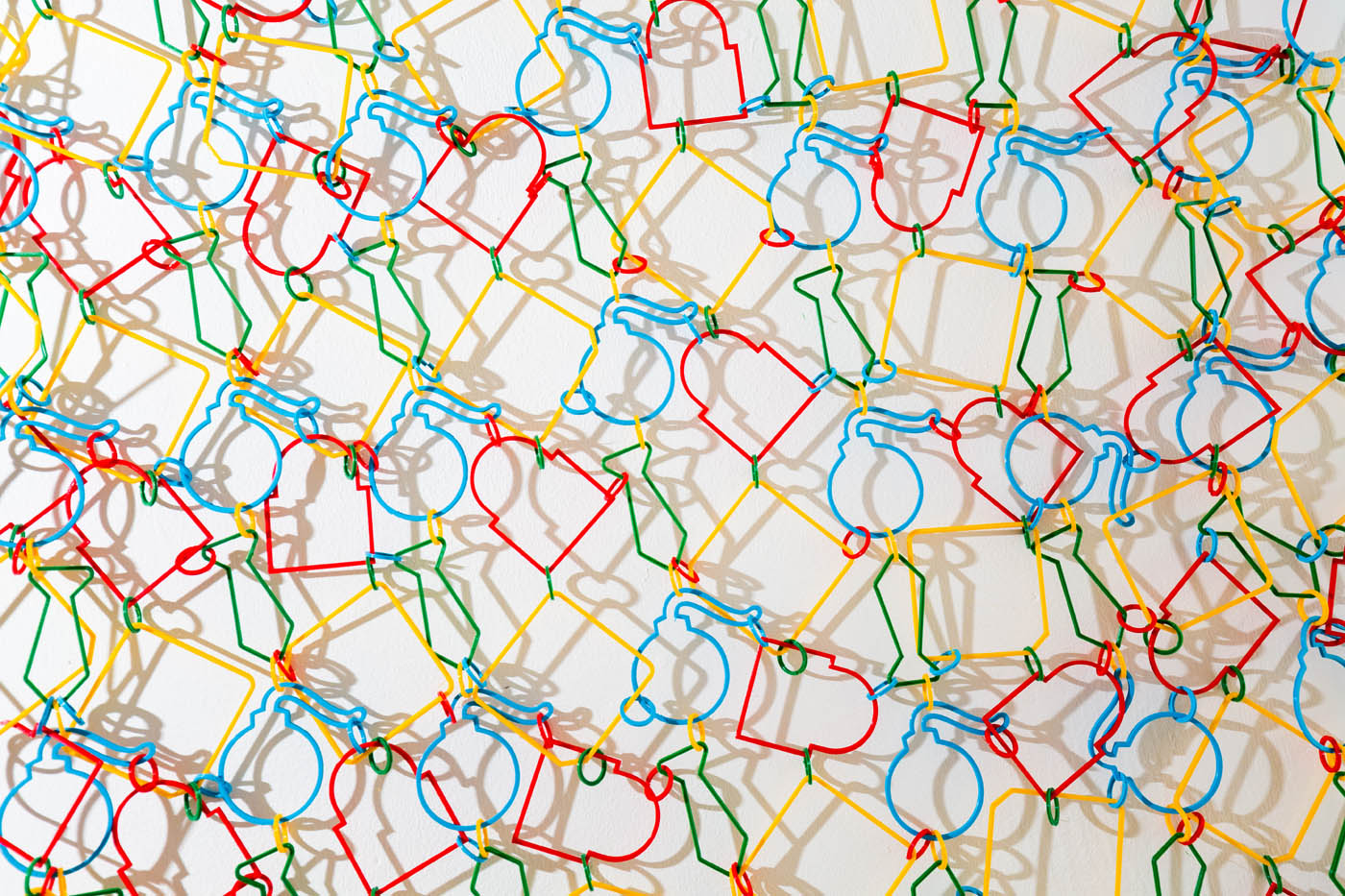

Although the themes you explore are clearly quite grave, on the surface, your work appears jovial, as you often use bright colours and designate each piece with a tongue-in-cheek title. Can you explain this tendency toward juxtaposition?

This was something that organically progressed over the last few years. I have always had a leaning towards quite seductive materials, i.e. ones that make you want to touch or have a particularly alluring finish, and this has developed into using their particularly enticing qualities as a visual trick to encourage engagement. So initially someone might be attracted inside an installation because of the materiality, but then upon entering, can hopefully begin to unpick what is going on beneath the surface.

How did you get involved with London-based gallery Light Eye Mind?

It was a happy coincidence! I had a grant to continue some work I had started on a residency in Berlin, which was looking at how the arts can be used as a tool to examine economic power structures, and had it in the back of my mind that I wanted to partner with a space to present the culmination of the work. Johnny Costi, a former Saint Martins student had put the word about that he was looking for socially engaged projects to host at Light Eye Mind, a space he co-runs with Goldsmith's graduate Alex Jeronymides-Norie and so the partnership was born. It was an absolutely brilliant experience working with them; there is a great team at the gallery, all of whom have a very positive ethos, and made the whole experience smooth and very rewarding.

And, lastly, what do you have in store for the future?

I am finishing off my final year at Saint Martins at the moment so beyond the degree show, I am working on a project funded by O2 looking at how social art practice can help address our economic knowledge deficit. I am also joining the team at Light Eye Mind gallery in North London where I had my first solo show. So watch this space for forthcoming exhibitions and events!

@alicejanewoods

A conversation with KAREN MARGOLIS from Rooms 16: Superluminal

Obsessively crafted circles are the central motif to Karen Margolis’ work. The circle, sacred to many, is riddled with symbolic meaning

Obsessively crafted circles are the central motif to Karen Margolis’ work. The circle, sacred to many, is riddled with symbolic meaning. In Chinese gai tain cosmology, the circle is noted as the most perfect geometric shape and, accordingly, represents the heavens above the square earth. In Native American tradition, the medicine wheel is a symbol of life, perfection, and infinites. Even hip-hop super-group Wu-Tang Clan, 5 Percenters, praise the purity of the circle. “As God Cypher Divine, all minds one, no question,” Masta Killa recites in Visionz. In hip-hop culture, the cypher refers to freestyle rap, where interrupting another man will break the cycle. According to the 5 Percenters and their supreme mathematics, zero (or the cipher) is the completion of a circle: 360 degrees of knowledge, wisdom, and understanding.

It’s easy to see how Margolis finds boundless inspiration and energy from the round wonder. Margolis repetitively creates the shape to map out the inner dialogues of the mind. Influenced by her psychology background, she is determined to show audiences how our minds work with her art.

Rooms: Would you mind telling us a bit about yourself?

What drives me as an artist is trying to find out who I am. I feel like I exist in a fluid state within the world around me, absorbing certainties of others with no absolutes of my own. I spend a lot of time studying people's behavior and writing about it. I'm influenced by Diane Arbus' observation of "the gap between what you want people to know about you and what you can't help people knowing about you". Her work made me hyper-aware of the unconscious signals we all send out and compelled me to look below the surfaces of others as well as myself, to see the reality; so, I am focused on trying to reconcile the inner and outer me.

Rooms: Your original field of study was in psychology. Does this come to play in your artwork?

Very much so. As a child I had a lot of phobias and had become somewhat obsessed with the idea that there is another sort of energy inside of me that I could not articulate. I had seen a movie called "Forbidden Planet" that featured invisible creatures from the id and that really got my attention. After that, I found some books in the library on the inner workings of the mind and psychology became a lifelong fascination for me. In college, I focused on the brain and Experimental Psychology, which dealt with processes that underlie behavior. I didn't know what I wanted to do with psychology and ultimately dropped out of Grad School. My route has been rather circuitous, but as an artist, I wanted my work to be about mental operations, to somehow capture the mechanics of the mind. Also, it couldn't be personal and had to be about the universal. I used myself as a subject because it was easier. As an avid diarist with over 20 years of journal entries and detailed narratives of my dreams, I thought that they might be good material to begin with and created a system to chart and encode my interior monologues by translating them into colored fields of dots. These compositions on paper are visual diaries, encoded interior monologues. Working from my journals, I translate feelings into colored dots. My rules are rather loose and, depending on the writings, I use one day or a week that I transcribe into colors. I simultaneously divulge and conceal my intimate feelings.

Rooms: The circle is evidently a key component to your work. It represents the molecule, a neurotransmitter and an Enso (the sacred symbol in Zen Buddhism). The circle brings science and spirituality together in your art. Is this how you manifest all your identities and roles at once?

I look for the connective tissue between the universe and the microscopic. I have found it in the circle. It relates everything. As the most basic component in the universe, the circle can be found in all of nature as well as in religious symbols, like a halo or the Sephirot in the Kabbalah. I practice Zen Buddhism and became interested in the Enso because it represents infinity, perfection, and totality. Layering my metaphysical beliefs with chemical reactions in the brain became the basis of my work. This way I am able to reconcile the physical with the metaphysical

Rooms: Is the process of creating the circles a form of mediation, personal psychoanalysis, or trephining?

Creating circles is immensely satisfying. In meditation, you focus on your breaths and clarity somehow emerges; as thoughts pop into your head you can see that they are not real and eventually you are not held hostage by your beliefs. My process has evolved into a synthesis of meditation, stream of consciousness thinking in which I work through obsessive thoughts, and physical pain, particularly when I am burning, which I metaphorically relate to trephining. I first learned of trephination (drilling holes into people's heads) when I wrote a paper chronicling the treatment of mental illness, and the torture of it stuck with me. It was repulsive and compelling.

Rooms: You had a series where you created circles with maps. What meaning did the maps bring to your work?

I'm drawn to maps because they offer an implicit promise that they will help you find your way. In my work, the maps act as proxy for the physical self. Additionally, they frustrate expectations of any help navigating through the world. I use maps to explore arbitrary destruction and regeneration in the journey of life. After burning holes in maps, I layer them on top of each other; passages to new locations are created in places that have been lost. I invoke into my maps my philosophy that in loss something new and unexpected is found.

Rooms: Are the colors you use to represent emotions based on socialization and culture or personal instinct of how they would look?

I wanted to develop a standardized flow chart of emotions and worked with the Pantone Color System to designate a color to each emotion and coordinate families of emotions to color families (tints, saturated hues and shades). I knew from the start of this endeavor that I would not be able to have an intuitively based color chart, but, where possible, I used expected colors for emotions, like green for envy. The charts are a continual work in progress; I add new emotions to the chart as they come into my consciousness.

Rooms: By playing with the circle, you affect its perfection.

I am attracted to perfection but celebrate Wabi-sabi, the Japanese philosophy around the beauty of imperfection, aging, and deterioration. I don't think people would be very interesting without their paradoxes. I reconcile oppositions within my work, "without darkness, there can be no light".

Rooms: Your work seems extremely meticulous. Are you a perfectionist in all other aspects of your life?

I do immerse myself in details; it is just how I operate in the world, it’s not planned or thought out. That said, I am anything but a perfectionist. My mind is such a roiling sea of chaos that obsessive as I may be, nothing is perfect and all is a compromise.