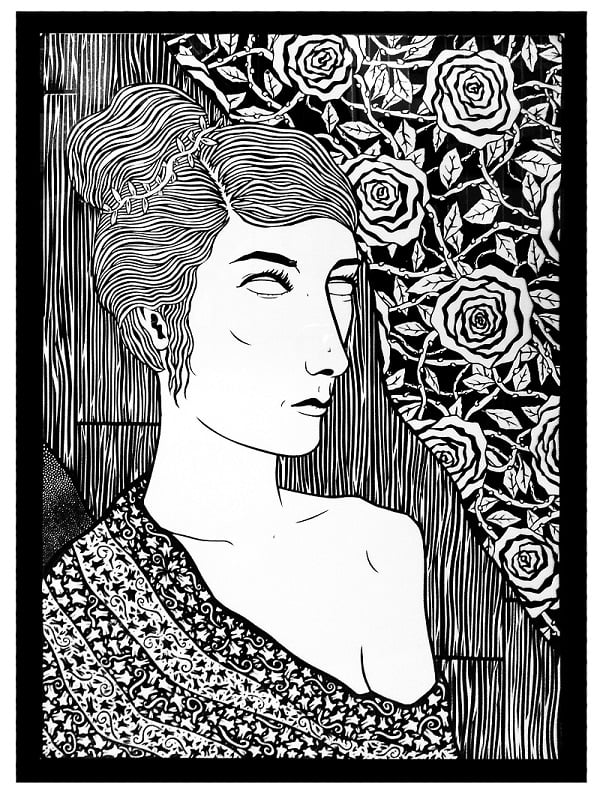

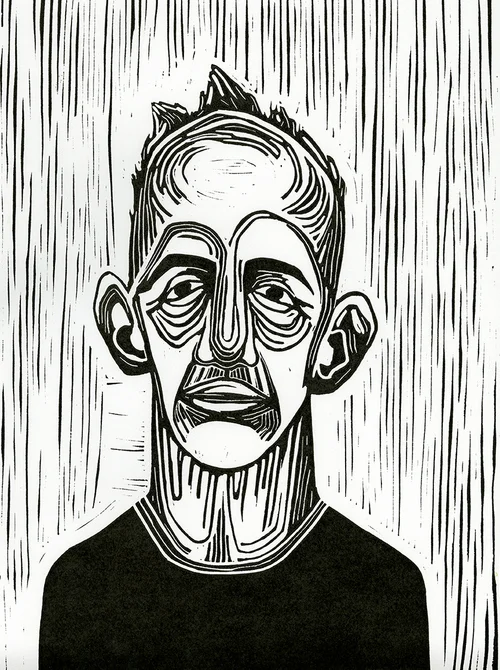

Gilded Chaos by Benjamin Murphy

Artist Rowan Newton interviews artist Benjamin Murphy ahead of his striking new body of work Gilded Chaos, showing at Beers London soon!

After The Day After

Artist Rowan Newton interviews artist Benjamin Murphy ahead of his striking new body of work Gilded Chaos, showing at Beers London soon!

Gilded Chaos

Preview: Thursday 14 January 6-9pm

Exhibition: 15 Jan.- 13 Feb 2016

Why have you chosen electrical tape as your medium? When did this begin, and do you feel restricted by it?

I did it after a few too many beers one night around 6 years ago whilst I was doing an MA in Contemporary Fine Art at The University of Salford. I like it because of its limitations I suppose. There are no books about ‘how to draw with electrical tape’, so any techniques or solutions I need I have to work out for myself.

Why do you always use black tape, as electrical tape comes in other colours too?

All of my work is black and white, even when I’m not using tape. It’s a much bolder and more striking aesthetic, the world is multicoloured and anything black and white stands out in contrast to it.

Your pieces have a confliction between life drawing and still life. Often a nude study is at the forefront but in a staged environment with many still life objects dotted around in the background. What do you prefer, the still life or the life, and what is it that interests you about the both of them?

I always have the ‘still life’ elements in the background, as a way of suggesting possible storylines for the main character of the artworks. They are both important but the background detail is only there as a way to add extra potential narritive for the subject.

What is your reason for so much pattern work within your pieces, is this because it looks pretty, or because it is a challenge to recreate such intricate pattern work; or is there something else to it?

It is partly just a way of challenging myself and pushing my limits, and partly because I decided to make this new body of work as detailed and lavish as possible to resonate with the show title. (Gilded Chaos).

“I want to leave the works ‘meaning’ up to the viewer to determine”

There is a strong narrative to your work, is the message a direct one you wish to tell, or is it for the viewer to interpret for themselves?

I’m always careful to suggest multiple possible meanings and messages, but in a way that their interpretations are multifarious. I believe in the pluralism of interpretation, as any viewer who looks at an image will see it in a different way. So for this reason I want to leave the works ‘meaning’ up to the viewer to determine. I like to hint at things, but ultimately I feel that most of the work should be done by the viewer.

Is there room for you in the art world for just pretty looking art, art work that is just there to be enjoyed for its attractiveness but not so much trying to convey a message?

There definitely is a place for it, but I find that it doesn’t hold my attention for as long as works with more substance to them than their surface aesthetic. Craftsmanship on its own isn’t really enough without something else.

Constanza

Within your narrative there are regular motifs that pop up, skulls, crucifixes but the one that stands out to me in the toilet roll, talk to me about toilet roll?

I thought that that particular work needed something that was almost plain white in the center to balance the image, and so my first idea was a skull. The vase of flowers and the urn obviously both already have strong death connotations so a skull would have been overkill. As it looks like it is in some kind of funeral parlor or something the toilet roll seems to fit in, also there’s something darkly comical about it, which I like.

Will we see toilet roll in this show?

Yes the toilet roll one is in the show, it’s called ‘In Praise Of Darkness’. It’s titled after a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, who has been a big inspiration for the show.

There is a play with perspective in your work, the angles of chairs not quite lining up with angle of the shelf or the bed or the table etc. What do these mean for you?

My use of perspective is quite important and people rarely pick up on it, so I’m glad you have.

Perspective is utilized by the artist to transform a two-dimensional plane into a three-dimensional space. This brings the viewer beyond the frame and into the artwork, as what is seen in the foreground is imagined (through the use of foreshortening etc.) to be at the front of the image. Perspective in a two-dimensional image is an illusion, and its immobile vanishing points is something that is never seen in nature. This already makes the artwork static and artificial, before the subject matter is even considered.

Perspective can be utilized to create feelings of unfamiliarity and otherness when used in the right way. When I draw the person in the artwork, they are seen from below, as if the viewer of the work is looking up at them. This is drawn in a contradictory way to the one in which I draw the background, as the background is seen as if the viewer were above it.

This imbalance in perspective is what creates the subtle but very real sense of unease in the viewer, as it is not immediately noticeable to be the source of the uneasiness. This difference in perspective creates two ‘artificial’ viewpoints that occur from every singular ‘real’ viewpoint.

“Like a pop-up book, the character in the artwork is forced out of the confines of the frame and into the real world”

The way that the subject and background are seen creates the illusion that the subject is in fact a giant in their surroundings, and is much closer to the viewer than they appear, and that they aren’t really situated in the background at all, but on the viewers side of the frame. By placing objects in between the viewer and subject, the subject is then forced back into the background slightly, back into the picture.

Like a pop-up book, the character in the artwork is forced out of the confines of the frame and into the real world. The person depicted in the artwork is brought into the real world, and not the viewer into the artwork as is created with the correct perspective.

These techniques with perspective deny the viewers eyes from properly feeling that they can enter and explore the artwork fully, which the perspective appears at first glance to invite.

Which artists have influenced/inspired you with there use of perspective in their work?

I’m a big fan of the expressionists, many of whom do their perspective a little off; especially Vincent Van Gogh.

There is a voyeuristic nature to your work, as if you’re looking into private moments, what intrigues you about these moments?

The work is voyeuristic in a sense, but it is intended in a totally non-sexual way. I am careful to make the subject non-sexualised and non-passive in her surroundings. It is more like the viewer is voyeuristically looking at someone going about their daily lives, but in no way are the subjects naked for the pleasure of the viewer. If anything seedy is going on it is the fault of the viewer and not the subject of the artwork.

I like the subtlety of how uneasy this makes the viewer feel.

Do you feel now that we as people are being observed in voyeuristic manner, as we expose ourselves almost daily on social media, especially Instagram?

I suppose we are, but we put ourselves out there to be looked at. No one can see anything you don’t first decide to post. Instagram and facebook are inherently narcissistic, but then being an artist requires you to be a bit of a narcissist to begin with.

Are you ok with that or do you feel you have to do it to help build your audience and try and connect with them on a more intimate level. If you did not have your artwork to expose, would you be on social media?

I think I probably would still be on it, but I wouldn’t take it anywhere near as seriously.

More often than not your subjects are naked, is this to do with vulnerability? There are also kinky aspects to your work, corsets, suspenders, knives, are you turned on by your work? Is there a sexual releases for you in your work? Who are these women and do these settings exist?

It is more to do with innocence than vulnerability in my mind. Lingerie and underwear tend to be sexy in a coquettish way, by suggesting that which they conceal. For me those items are more of a way in which to cover up something, which in turn is a way of making the work not so much about sex. I don’t like to draw fully naked character as its tough to have them still appear tasteful and non-sexualised.

What frustrates you about your art and the art world around you?

The only real times I get frustrated with my work is when I can’t find time to be drawing, or when I’ve been drawing for so long that I can’t tell what works and what doesn’t. In the art world in general I’m most frustrated by the continuous rehashings of pop art that are so ubiquitous these days, Pop Art ceased to be interesting a long time ago.

Face to face how do you find talking about your work, is it something you are comfortable with, or shy away from?

I don’t mind it so much, I find that I often talk too fast and go off on tangents for far too long though. I’m much more coherent when I’m writing it down.

You have a solo show at Beers Contemporary coming up. What is the theme of this show and have you approached it any differently to past shows?

I’m really excited about showing with Beers, they are a great gallery and have been amazing to work with this far. To be even listed as one of their artists is an honor.

There isn’t a theme as such, but all the works relate to one another in some way. There is a lot of detailed floral pattern running throughout the works, partially inspired by William Morris. These works have taken a lot longer to produce than the works for my previous shows, due to the level of detail et cetera. This in turn has meant that as I’m working for much longer, my inspirations are all the more myriad.

What was the biggest challenge to putting this show together?

The level of detail has been a big challenge, as the smaller you go the more difficult it is. It’s also hard to spend days drawing the same pattern over and over, it makes you go a little insane.

What do you want people to walk away with once seeing this show?

I want people receive so many different and contradictory thoughts and emotions that they don’t fully understand them until they go away and ruminate on them. I also want the show to have a lasting impact in some way, be it positive or negative. Anything as long as it isn’t ambivalent.

The story of painting rascal Ide André

“Everyone can say what they want, but I do hope that my work comes across as fresh, dirty, firm, crispy, dirty, clean, fast, strong, smooth, messy, sleek and of course cocky.”

“Everyone can say what they want, but I do hope that my work comes across as fresh, dirty, firm, crispy, dirty, clean, fast, strong, smooth, messy, sleek and of course cocky.” – Ide André

Somewhere between the concrete walls of the Institute of the Arts in Arnhem, a talented kid with a big mouth and an urge to paint was bound to challenge perspectives. Years later, he found himself rumbling in his atelier, experimenting with ideas and creating things out of chaotic settings. With a determined attitude and an open mind, he managed to turn everything into a form of art. Some people liked his work, some people questioned it; either way it got attention. Right now, he’s working on several projects all exploring the relationship between painting and everyday life with the carpet (yes, the carpet, I told you this guy can turn anything into art piece) as main subject. His work is a reflection of his personality: bold, impulsive, fun and with a fair amount of attitude. He however likes to use a couple more words when describing his own work. This is the short version of his biography, the end of my version of his story. If you prefer a more authentic one here’s the story in the artist’s words:

I once saw a show of Elsworth Kelly when I was a child. The enormous series of two-toned monograms clearly made a big impression on me. I remember staring with my mouth wide open at the big coloured surfaces. I’m not that much of a romantic soul to say that it all started right there, but it did leave an impact on me. I actually developed my love for painting at ArtEZ. I started out working with installation art and printing techniques, but I was always drawn to the work of contemporary, mostly abstract painters, until I actually became fascinated about my fascination with abstract painting. Because, let’s be honest here, sometimes it seems quite bizarre to worry about some splotches of colour on a canvas. Even though painting has been declared dead many times over, loads of people carry on working with this medium no matter what; from a headstrong choice, commitment or just because they can’t help it. I am clearly one of those people, and that fact still manages to fascinate me.

At ArtEZ you talk so much to your fellow students, teachers and guest artists, little by little you kind of construct your own vision on art. And that’s a good thing! All this time you get bombarded with numerous opinions, ideas and assignments, some of them (as stubborn as we are) that seemed useless to us and weren’t easily put on top of our to-do-list. Until there is that moment you realise that you have to filter everything and twist and turn it in your own way. Then there is that epiphany moment. That moment you realize you can actually make everything your own. I think that’s the most important thing I’ve learned during University: giving everything your own twist and constantly questioning what you are doing, subsequently always struggling a little bit but still continue until the end. Like an everyday routine.

I’m not going to enounce myself about the definition of art. That would be the same thing as wondering what great music is or good food. I think it’s something everyone can determine for themselves. I do think it is interesting to ask myself how an artwork can function and what it can evoke. There is this exciting paradoxical element within art. On the one hand we pretend that art should be something that belongs to humanity, something that is from the people, for the people; on the other hand is the fact that art has its own world, its own domain where it can live safely, on its own autonomous rules, and it doesn’t have to be bothered by this cold, always speculating world. There are pros and cons about both sides, and I think it’s impossible to make a work of art that solely belongs to one of the two worlds. As Jan Verwoert, Dutch art critic and writer, words it: “Art as a cellophane curtain”. Without getting too much into it (otherwise I’m afraid I’ll never finish this story), there is this see-through curtain between the two worlds. The artist is looking at the outside world through his work, and the outside world looks at the artist through his work. That’s how I see art and how I approach it.

My work often comes about in various places, with my studio as a start and end point. I buy my fabric at the market and from there the creative process really starts. I print on them, light fireworks on them with my friends, or sew them together with my mother at the kitchen table in my childhood home. I try to treat all these actions as painting related actions. Like a runner that goes to the running track on his bike; we could ask ourselves: is he already exercising running? On an average atelier day, I toil with my stressed and unstressed fabrics, chaotically studded around the room. Usually I don’t have a fixed plan. My process is semi-impulsive and comes from an urge. Often this causes little and mostly unforeseen mistakes, these ‘mistakes’ often prove to be an asset in the next project.

As for the future, (Lucky for me) I don’t own a crystal ball, so I wouldn’t dare to make predictions. And quite frankly I wouldn’t want to know. Young collectives, initiatives and galleries keep popping up and I think we continue to grow more and more self-sufficient. Of course there is that itch of our generation to always learn more, do more; an urge that I believe will never disappear, also not within myself. I will stubbornly continue to work on the things I believe in. Not because it offers me some sort of security (most of the time it’s the opposite) but because I just can’t help it.

Alexandra Uhart – real stories through the power of image

With a mission to document real life, and an execution that is unique and compelling in every way possible, ROOMS' photographer Alexandra Uhart stole our hearts and will soon devour yours too.

Since the last month of my masters, I’ve transformed my home into my temporary studio. I live in a newly built flat with big white walls, two of which at the moment are covered in photographs, sketches, sticky notes and diverse research material that I have been gathering for my latest work “Someone here”. I’m sitting at what used to be the dinning table, and now transformed into a desk. I have a laptop, books, a couple of pens and a glass of water in front of me. From here I face the window. It’s raining heavily outside, I’m happy to be working in today. If I were to photograph this, I would set up my camera on a tripod and shoot the scene from behind me. The photograph would capture me facing the window from across the table, showing the artist behind the work and the process behind the photos. I would maintain a certain mystery by facing away from the camera, giving the viewer an opportunity in doing so to connect the dots and make up their own story about the scene.

ROOMS' long time photographer Alexandra Uhart has just completed her Photography Masters at the London College of Communication, and her series Someone Here is the Winner of the Photoworks Prize 2015. With a mission to document real life, and an execution that is unique and compelling in every way possible, Alexandra stole our hearts and will soon devour yours too.

When did you know you wanted to be a photographer?

Photography has always been a passion of mine. My first camera was given to me on my 9th birthday. It was a little Ninja Turtles themed film camera, which took photos that had a Ninja Turtle stamp in the right corner of every print. I remember photographing my toys with it; organizing them in groups and posing them amongst very elaborate settings. As I grew up and upgraded my photo equipment, I started photographing my friends. I would spend the afternoons borrowing make-up and clothing from my mom and styling photo shoots with them as models.

However it didn’t occur to me to study photography until years after I left college. I tried being traditional at first and went to law school for a couple of years, quickly realising that it was not for me. After that I decided to study Aesthetics. I really enjoyed it but I wasn’t sure where it would take me, since I felt like something was missing. It was not until I moved to Paris in 2009 that I decided to pursue photography, realising I wanted to be the one creating and not just theorising about other people’s creations.

Where do you go for inspiration?

I think everything can inspire me at a certain moment; inspiration can come from so many different places and I go and search for different things depending on the work that I am looking to produce. I would normally start by doing some research on an idea and moving forward from there. The truth is reality can be immensely inspiring.

When is a scene good enough to be captured?

I think every scene is good enough to be captured, depending on what you’re looking for. My work comes from a documentary and street photography tradition, from capturing the life around me and trying to understand it through images.

I’m motivated by humanity; how we interact with each other and with our environments. In my latest series “Someone Here” I’ve focused on different aspects of our current struggles with the environment. In this media-driven world that we live in, photography has the opportunity to be shared easier and faster than ever before, making photography an invaluable channel of communication in raising awareness. What we choose to photograph can actually make a difference in the world.

“What we choose to photograph can actually make a difference in the world.”

Your portraits have a very authentic feel to it. Tell me something about your process of shooting portraits. What is your goal, and how do you achieve it?

I really enjoy taking portraits. Most of the ones I shoot are set in people’s studios or houses, which helps give the photograph a more intimate feeling. However, the camera can be very invasive so it’s very important for me to make my subjects feel at ease quickly. My goal is to reveal something about them, to show an aspect of their personality. I have to say that the most important part of the process happens before taking the photo. I do my research, I prepare everything. Then I go to their homes or their working spaces. Once I get there I talk to them while setting up my equipment. I love getting to know people, having the opportunity to capture something special about them with my images.

I’m fascinated by your photo series 'mind trap'. It conveys however a very different style and feeling than the work you did in the beginning of your career. Can you tell me something about the concept?

‘Mind Trap’ was one of my first incursions into fine art photography. After years of working in more commercial areas of photography, I decided it was time to explore my personal interests and move to a setting that would allow me to freely express my views. I created this series when applying for the Photography MA at LCC. My inspiration came from a deep concern I have for our environment and its species. In the past years we hear of an increasing number of animals that are going extinct due to our careless appropriation and treatment of their ecosystems; with these images I aimed to mirror the way in which people have been confining them into man-made spaces where they don’t belong.

Any exciting projects in the future?

I just finished working on my new series “Someone Here” a documentary exploration of the Atacama Desert in Chile, where the rise of the mining industry has led to an alarming environmental detriment. As a Chilean artist, I think it is important for me to show the stories of my country and help raise awareness of its problems. I am currently exhibiting this work at LCC College as part of the MA Photography show. I’m thinking of creating a book with the body of work and some of the research that led to the creation of this project in the near future.

Since film is an area that I have also always been very interested in, I am eager to start working on a collaborated film project with Chilean-Swiss director Nicolas Bauer that will be shooting in Miami next year.

After that, I see myself continuing on the path I am now: combining fine art photography and film. However, as I evolve as an individual so will my way of looking at things and photographing them. It is essential to keep reinventing myself as an artist and photographer, but I hope to do this while still being faithful to what’s drawn me to photography in the first place: telling real stories through images, documenting life.

Dele Sosimi

Dele Sosimi stands out as one of the most active musicians presently on the Afrobeat scene worldwide. Here he talks about duty to Afrobeat, relentless performances and his latest CD.

Dele Sosimi stands out as one of the most active musicians presently on the Afrobeat scene worldwide. Here he talks about duty to Afrobeat, relentless performances and his latest CD.

His tutor and guru was one of the world’s most feted and controversial music icon - Fela Kuti, also known as Fela Anikulapo Kuti or simply Fela - before his family, bandmates and friends and indeed the world was rocked by his passing on August 2, 1997, from Kaposi's sarcoma which was brought on by AIDS. Nonetheless, this loyalist, representative and artist - Bamidele Olatunbosun Sosimi, known as Dele Sosimi, from teenage keyboard player for Fela Kuti's Egypt 80 to bandleader for his son Femi Kuti's Positive ensemble, was tutored and raised in Fela Anikulapo Kuti’s shadow and worked and travel around extensively with Fela around the world at the pinnacle of early 70s Afrobeat fever. Picked by Fela to join his band at a somewhat tender age, he was still a young man when sharing Fela’s Glastonbury stage in 1984. But be that as it may, Dele Sosimi - born in Hackney, East London, raised in his native Nigeria from the age of four, refutes to slow down. He is here and now one of the leading forces/important voices of Afrobeat holding fort the Afrobeat music on the Afrobeat scene internationally.

After Fela’s passing in 1997, Dele went on to concentrate on his solo career and, with meticulous endurance, sliced out his own Afrobeat trophy in London, where he now dwells. Totally, this Nigerian-British boy is done admirably well. Sosimi has helped define the sound alongside some of its most iconic figures – he is an inspiration to many. Check this out: Vocalist? Tick. Keyboard player? Tick. Producer and Afrobeat giant? Tick. And the founder of his own orchestra? Tick. In addition more recently he was the Musical Director & Afrobeat Music Consultant for the award winning musical FELA! Currently on a global tour. And what’s more? Sosimi is an Afrobeat Composer, Producer, Musician, educator and instructor (via London School of Afrobeat) as a Visiting Lecturer at London Metropolitan University, Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance - the UK's only conservatoire of music and contemporary dance and Cardiff University.

Once again an experience awaits with another marathon session (four-hour-non-stop) of keeping Afrobeat, the music, spirit & legacy of Fela Anikulapo Kuti alive in London at The Forge, Camden, UK

Saturday 28 November 2015. The Dele Sosimi Afrobeat Orchestra are a gang that must be seen live in all its astounding fierceness. Dele is returning to London for his third Album lunch gig ‘You No Fit Touch Am,’ a 7-track collection of compositions – his third solo album and his first for 10 years that is immersed in socio-political messages and showcase classic 1970s Lagos song writing. “You No Fit Touch Am” was recorded in London with a crew of long time players and producer Nostalgia 77 (Tru Thoughts) presenting a 21st century clarity to the mix. There's no silly compromises to the music here though, just a thoroughly modern sense of energy in the mix with an aptly heavyweight bass charisma.

Dele Sosimi: Afrobeat Vibration is my way of keeping Afrobeat music alive and accessible to Afrobeat music lovers and musicians in the UK bi-monthly, are creation of the spirit and ambiance of Fela's Afrika Shrine.

Why are you staging a four-hour-non-stop musical marathon? Why 4 hour non-stop and why the chosen venue? Can you really keep this up?

Dele Sosimi: I stage it because it is a duty that must be done by me as an ambassador of the genre and culture. It is an experience hence it is 4 hours nonstop as we take you on a journey based on the repertoire selection for the night. We initially used the New Empowering Church in Hackney till November 2014 when the lease expired. Since then we used the Forge in Camden once before moving to Shapes in Hackney Wick May 24th 2015. We chose Shapes because it had the ambience size and potential for a late license till 5am. The importance! People or musicians who did not have the opportunity to listen to live afrobeat now have a regular bi-monthly platform that we have kept going for 7 years - last Saturday of January, March, May, July, September and November which is usually the anniversary month. We cover a wide range of Felas Classics and original new compositions featuring a wide range of guests and young musicians who have either attended one of my Afrobeat masterclasses or workshops. This year we are celebrating the 7th year of keeping it going.

Could you reveal names of guest stars contributing to this extravaganza on Friday November 28th? And what should fans expect?

Dele Sosimi: We never know who will turn up until the night itself bit we have had Tony Allen, PA Fatai Rolling Dollar, Cheick Tidiane Seck, Afrikan Boy, Breis, Shingai, Byron Wallen, to name a few.

Fans should expect to be delightfully Afrobeaten up.

You have a new album out - third album -”You No Fit Touch Am”. Tell us more about this album - and why the title; "You No Fit Touch Am?"?

Dele Sosimi: Release earlier this year by WahWah45s on the 24th of May, the literal meaning is “You cannot touch it”. On a conceptual level "the thing is too cool", "too tasty to be messed with", "you can't even come close", "and it is beyond you". "The jam just baaad", "don't look at it with common eye" with regards to what I do, what we do, the experience we provide, the spirit of music. Identity my 2nd Album was released 10 years ago, and I had made up my mind the third Album would have to wait for the right conditions, right record label at the right time with an offering of a clear development of the Afrobeat idiom, an important restatement of what Afrobeat is about, in the current scene where the term is used quite indiscriminately (and unfortunately confused with the rather more superficial “Afrobeats”). I strongly believe this is now the case. Suffice to say its taken 10 years but once the record deal was in place from recording, production to release nine months as most of the songs had been written years ago.

What is your message here?

Dele Sosimi: It depends on which angle you look at it from. Spiritually be open, tolerant and aware, appreciative and humble. Musically, there is a jewel of infinity contained here that will most likely be missed by many, who lack the ability to see the greatness in small things. On the other hand, beauty will be discovered and found here by many. Mainly the message draws attention to the state of things worldwide today with songs like "Na My Turn" (Elections worldwide with special attention on so called democracy in Africa pre and post elections) ~ “E go betta” (Despite facing abject poverty the admirable spirit of resilience and resolve to carry on and soldier on with the song of hope for a better tomorrow)~ “We siddon we dey look” – (Ferguson incidents, Boko Haram, ISIS and most recently Xenophobia) “Where We Want Be” (The intolerance prevalent in world society with the message being bring love back BIG TIME!) “Sanctuary”- (In line with Fela’s “Music is the weapon of the future” message. In this case music being the Sanctuary where you recharge your batteries to keep on) and “You No Fit Touch Am” as earlier indicated.

What drives Dele Sosimi?

Dele Sosimi: Breath, life, love and family drives Dele.

Saturday 28 November 2015

Shapes, London, UK

Shapes, 117 Wallis rd. Hackney Wick E9 5LN

Cost of Tickets: £10 Adv. £12 Otd

Tuesday 09 February 2016

Kings Place, London, UK

Introducing: Nick JS Thompson

We interview photographer Nick JS Thompson ahead of his forthcoming show The Decline of Conscience at Hundred Years Gallery.

ROOMS presents: The Decline of Conscience by Nick JS Thompson

Curated by Benjamin Murphy | Hundred Years Gallery

19 - 25 Nov'15

Nick is a photographer with a strong sense of social conscience, and his work is always both beautifully alluring and ethically charged. This duality is what balances his work perfectly in-between honest documentary photography and fine art.

Often his photographs show human-altered landscapes, long after the people charged with their intervention have left them behind. These ghostly but familiar images are both beautiful and almost frightening.

BM – Is photography a nostalgic art form, always documenting the past?

NJST – Not necessarily. For my work yes possibly; it is rooted in nostalgia. I create work that explores events that have happened in the past and what people’s actions have been. Maybe that is a nostalgic act but I still wouldn’t class my work as nostalgic. I think it depends on the type of photography though. Something like still life photography, which is created in the present with a certain purpose in mind, could be anything but nostalgic.

BM – Are photographers creating or recording a reality? And do you think you can do one without doing both?

NJST – That’s a hard one, I think both are true. Obviously if you are a photojournalist and covering a story, you should be recording reality as it happens or as it happened in the past. Photography is such a broad term that it encompasses things such as fashion photography where each situation is carefully controlled and created to evoke a particular emotion or put across an aesthetic which has been chosen by the photographer.

BM – Susan Sontag said that no two photographers can take the same photograph of the same thing, do you agree?

NJST – Yes I do, I think that even if two photographers are photographing the same scene at the same time the images will each be different. Every person has a different take on things, what their views are on the subject matter, and emotional insights, and biases that each person has.

BM – How much control over the final image can the photographer actually claim, due to lighting changes, wind, shutter speed etc.?

NJST – Again this depends on what type of photography you are talking about. The phrase that Henri Cartier-Bresson coined is that of “the decisive moment” which he sums up by saying "the decisive moment, it is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as the precise organization of forms which gives that event its proper expression." This is taking the chance events that are happening around you and trying to control them to the best of your ability in one image. This is true of documentary photography, or the street photography that Cartier-Bresson is famous for, but if you are creating a still life in a studio then you obviously have complete control of every aspect of the image.

Fanø

Fanø

BM – Should photographs only be viewed in print? As then the artist can control exactly how it is encountered. Screen brightness and quality affect how it is seen, is this a problem?

NJST – I definitely prefer people to see my work in print. Viewing work online also affects your concentration, people flick through thousands of images and don’t give them as much attention as they sometimes deserve. (I know I’m guilty of it.) It is very easy to become desensitized with an endless stream of images from your computer screen or smartphone. The display quality is also definitely an issue, presenting images, which have sometimes been compressed and the resolution reduced. These things can greatly influence and detract from the viewers experience with an image.

The sequencing of pictures in a series is also extremely important for me to tell the story that I want. In the digital world this is often lost; which is why the recent surge in self-published photo books, with people like Self Publish, Be Happy leading the way. I think that is an incredible thing.

BM – Do you think smartphones and the Internet have ruined photography?

NJST – With platforms such as Instagram, where images are presented in an endless list and shown on a small scale, on screen, like I said before I think has definitely affected photography in a negative way. I wouldn’t say that it had ruined it per se but the knock on affect for a new generation of photographers and artists viewing work in this format I’m sure will have repercussions down the line.

“it is really interesting to see how people alter things for purposes that maybe no longer matter or aren’t relevant any more”

Having said that, I think that digital has a place in the world of photography and obviously it is here to stay so we just have to look for ways to use it in different ways; to embrace it and use it in a way that compliments the technology.

BM – You take photos and make videos, what does photography have that video doesn’t?

NJST – They are such different disciplines for me. In my opinion, photography can be more powerful. A still image can be looked at for as long as you want, and is often seared into you brain. The length of time you can look at it and the attention you can give to it mean that it can have more of an impact.

Video for me is more of a whole atmosphere that can be created encompassing sound and images. This is more on par with a photo essay or series of images to make up a whole picture of events or what you want to portray.

BM – You take mainly portraits, but more specifically portraits within landscapes. What are the relationships between the two?

NJST – My work looks at the effect and marks that people have left on a landscape or surrounding. I think it is really interesting to see how people alter things for purposes that maybe no longer matter or aren’t relevant any more. My work on Fanø for example was documenting the huge number of bunkers that cover a small island off the coast of Denmark, built by the Nazi’s during WWII. Their purpose has completely changed, and they are obsolete. Their appeal to the viewer now is at first glance more aesthetic than functional, although they have undertones of what the original purpose was, and this adds a sinister layer of emotion to the work. Or the work that I have shot over the last few years around the Heygate Estate in South London, again is a record of how people have changed the environment in which they live and the constant changing of this for better or worse

The Decline of Conscience

BM – Are these the fine art photographs and your Cambodia ones more documentary?

NJST – Yeah, some of the work I shoot when I travel is more based in the traditions of documentary photography. The Fanø series is a lot more calculated and thought out over an extended period, where as the travel documentary photos are usually more off the cuff and going with the flow of what is happening around me at that particular time.

BM – Why do you choose to show the documentary works in a fine art setting?

NJST – Documentary work can definitely be shown in a fine art setting. It depends on what your thought processes are behind the images and work as a whole. For me, my work falls under fine art to an extent because of the ideas behind what I am trying to portray visually to people. I choose to show the work in a fine art setting because it gives me a space to explore the work and display the work exactly how I want it to be viewed instead of handing it over to a picture editor and letting them then edit and govern the work, possibly even changing its intended purpose to fit a particular agenda. I think it is maybe me being a bit of a control freak over the work and over people’s experience of viewing it.

BM – Do you think that once you have taken a photograph of something, that the act of you taking the photograph changes it forever or are you entirely a voyeur?

NJST – I like to think that it doesn’t change it, but I think possibly it does. It’s a question that I constantly ask myself. If you are going to enter a person’s personal space or environment to take a picture then I think that inevitably you are going to effect their behavior in some way. This is why I prefer to spend longer periods of time with people so that they become used to me being around and then almost forget that I am there. This is the ideal.

Phuomi

BM - Often your work is rather bleak, what is it about this kind of photography that attracts you?

NJST – For me it some of the most interesting human emotions are fear or distress. I don’t know what type of person this makes me (Laughs). They are extreme and when people are in these states it sometimes makes them behave in odd and interesting ways. For me putting myself in uncomfortable situations either as they are happening or after the event, pushes me to create work that reflect these extremes.

I also find it interesting to see how viewers engage and react to work when confronted with images that are uncomfortable to look at.

BM – My favourite of your works are the empty rooms, what do you think these can say that a portrait can’t?

NJST – This links back to showing how people have altered their surroundings and the effect that this has on the atmosphere of a space. Vilhelm Hammershøi is a massive influence on my work, with his paintings of rooms with often-muted tones and somber ambiance.

It is documenting everyday life but when you take the people out of the image it slows things down for me, I can concentrate of the finer details of the scene that I think can be extremely telling in what that person is like. And this adds to it being a more complete picture.

The Decline of Conscience by Nick JS Thompson | facebook event

19 - 25 November at Hundred Years Gallery

Curated by Benjamin Murphy

Mr. Gresty : A brander in its most innovative interpretation

A brander by nature, an illustrator by heart, a curator by interest; but for everyone else just Mr. Gresty.

A brander by nature, an illustrator by heart, a curator by interest; but for everyone else just Mr. Gresty.

Being a designer for a multitude of companies, what makes you want to work with a brand?

A lot of my design work is branding start-up companies. I especially enjoy this area. Seeing the client’s excitement and enthusiasm towards my ideas and their new brand. I love working together on something like that, something new and fresh.

How would you describe your design identity and how does it show in your work for other companies?

I love to work with vibrant and positive colours and I always use a sense of humour and simple shapes in my work. In most cases my clients have seen other projects of mine and ask me to do my thing for them.

Tell us about the process of becoming the multitasking artist you are today.

I can’t let myself run out of things to do, if I do I feel lost. My system consists of working on all the commissioned projects first and then filling the gaps with all those personal projects. The variety of work keeps me stimulated.

You are a graphic designer, an illustrator, an author, a curator... How did you get involved with such a variety of work?

If I have an idea that in my opinion is worth trying, I’ll give it a go. As I work for myself and don’t have employees, I have the time and space to experiment. All those job titles share a characteristic; they are all creative solutions to a problem.

Many people say this is the future of the creative industry, the more you can do the higher you will get. Do you believe this is true?

I think that in the commercial world this could look good on a CV but on the other hand you can come across as a jack-of-all-trades, master of none. Some creatives will evolve their style and move on to the thing that they’re passionate about and pick up skills along the way. I believe I am one of those last creatives.

Working with typography a lot, what is your favourite font?

I don’t have one. Helvetica? No I don’t have one.

Is there a creative you are dying to work with?

I’ve never thought about it. To be honest I prefer to work on my own, but I am open to offers!

When did curating become a part of your career? What is it that attracts you to the field and what is the craziest idea you have ever had for an event?

In 2010, I started screen-printing and enjoyed it very much in Uni. I was in a bar in Clapton, Hackney, soon after speaking to the owner about the art on his walls, he said if I was interested I could put my work up! I said yes. At this point I had only created two typographic screen-prints. After a few solid weeks of printing lots of ideas from my sketchbook, I hung my first solo exhibition. Five years later and I’m getting ready to hang my 22nd exhibition. With the mixed exhibitions I enjoy seeing the variety of creative solutions to the same brief and like seeing my name in the line-up with artist who I admire.

The most creative and challenging exhibition was Whisper, based on the old game ‘Chinese Whispers’. I illustrated the first piece and gave it a title, I passed that title to the next artist and told them they could change the title slightly and that new title was their brief, then I passed their title to the next artist and so on!

You have been curating LHR exhibitions for the past two years. In your opinion, what is special about this 15th edition?

The 15th LHR Exhibition – The Things I Think About, When I Think About Thinking, has been the most open brief yet. I had been thinking about the mainstream media and that if something is bland and non-threatening it does well. I have created a small handful of pieces over the last few years that I am happy with and others that I’m personally not keen on; I have noticed that these last ones sell really well and my favourite pieces not so much. So the brief was for the artists to submit their very own favourite personal piece, not following trends or public demand.

The LHR exhibitions have taken place in bars, the entrance doesn’t cost a penny and is open for everyone and the artists are as free as can be in the work they deliver. All these elements make for an experience that is everything but your everyday gallery stroll. What inspired you to create these events?

I wanted to be able to hang a collection of work, where lots of people would see it, hear about the artists and wouldn’t have to pay to see it. At the same time I wanted it to be available to purchase and when a piece sells for that artist to be able to keep 100% of the money. I don’t think a bar is the best environment for art but it helps me achieve the issue of cost. All it takes is some time and life is long, I have lots of free time!

The Things I Think About, When I Think About Thinking

November 6 - January 31, 2016 at The Hanbury

Line-up: Mr Gresty, Claire E Hind, Ian Viggars, Freya Faulkner, Shona Read, Emma Russell, VJ Von Art, Lee Bromfield, James Dawe, Jake Townsend, Wiktor Malinowski, Dan Buckley, Dan Huglife, Jeff Knowles, Dylan White, Simon Fitzmaurice, Steven Quinn, Ricky Byrne, Stina Jones, Silvia Carrus, Julian Kerr, Nathan James Page III, Sean Gall, Josh Bond, James Morley, Craig Keenan and Raiph Vaughan.

This is the 15th LHR exhibition and sadly my last. I will keep you posted.

LHR Exhibition curated by Mr Gresty. 2013 - 2015

gresty@mrgresty.com

Ilse Moelands : A touch of heart, a mark on paper

Dutch illustrator Ilse Moelands’ drawings awaken emotions in an utterly beautiful way. Freshly graduated, she’s on the verge of publishing a book and continues to translate her fascination for the Far North into stunning drawings.

Dutch illustrator Ilse Moelands’ drawings awaken emotions in an utterly beautiful way. Freshly graduated, she’s on the verge of publishing a book and continues to translate her fascination for the Far North into stunning drawings.

Ilse Moelands: I’ve always doubted about my future and thus I had a lot of difficulties choosing the right study; would I become a doctor, an artist? I have always loved fashion and it’s influence on our culture and identity. To me fashion is about people and their characteristics and for a while I wanted to continue in that direction, ignoring the fact that I can’t sew at all. I thought I’d give it a go and ended up enjoying the drawing part the most. I wanted to draw all the time, so I decided to change studies and go for Illustration Design at ArtEZ. I like the directness of drawing and printing. Sewing and designing fashion is a much slower process.

Tell me something about your drawing process.

Often my urge to draw awakens when I am fascinated or frustrated. Then my ideas flow out of me on paper. I like to draw when I am alone, because I really have to be focused and concentrated.

You use a lot of older techniques such as thinner press and lino press, this is quite unusual in our digital era. Why these techniques and how did you come in touch with them?

I like to start with something physical, so I can smell the material; I want to have paint and ink on my hands. I just love the imperfection. It’s not that I don’t like digital work. I think there are a lot of possibilities working digital, but it’s not my cup of tea. At the art academy we had a really nice printing workshop. During my last year I spent as much time as possible in the workshop experimenting with all kinds of techniques and became intrigued with the older ones.

Your work instigates deep emotions, from the love for family to shame and loneliness. Are these feelings you experienced yourself when working on your drawings?

Yes. I always start with a very strong emotion, because it’s the only way I can make satisfying images. I think the world is a weird, crazy place and making art is my way to deal with that. It’s like therapy. But I try to make my work for other people as well. Emotions are a good starting point, but I always try to twist it in a way, so a lot of people can relate to my stories and images.

Where do your ideas come from and when is an idea good enough to execute?

People and their stories inspire me a lot. I am pretty hard on myself, so things aren’t good enough for me very easily. But I am still learning to let go of this perfection, and sometimes I overthink things and I stop myself from making art. But I always try to remember that small ideas can lead to big beautiful projects.

Talk to me about your fascination with the Far North, what is it that attracts you to it and inspires you to create illustrations?

I have worked and lived amidst the snow, polar bears, seals, and Inuit, I grew a fascination with the extreme living conditions those people have to deal with and how they remain a balance of sensitivity and strength. The hard, isolated existence and the respectful way these people treat nature provide the basis for the graphic story I’ve created for my graduation. The Inuit are very proud people however I can’t help but feel they are a bit lost, uprooted from their original culture as times have changed so much there. This idea had an immense impact on me and on my work. I went there with a lot of questions, but I came back with even more. I would love to go back there one day and maybe live even more primitively and remotely.

You went to Upernavik, Greenland for half a year. How did you end up there and what is the most important thing you’ve learnt?

A year ago I applied for the Artist in Residency Program in the Upernavik Museum. After waiting impatiently for a very long time, I was so happy when I received a letter saying they had chosen me to go there. The most important thing I learnt during my stay in Greenland is to be more calm and relaxed. Nature dictates the rhythm of life, so you either go with the flow or feel very miserable. I had to let go.

You're currently working on a book with Julia Dobber; tell me something about this project?

Next to the Greenland project, I needed something else so that when I was stuck with one project, I could escape into the other. I met Julia through a mutual friend and I instantly fell in love with her stories. Her work is about people who get through things, but nobody knows exactly what. For my graduation we compile six stories and complimenting drawings. Finishing them we both felt that there needed to be more, so our plan is to make twelve in total. I can’t wait to continue our exciting project and have the finished product in front of me.

Is there a particular artist you would love to work with?

Several. I really like the work of photographer Jeroen Toirkens. He’s a Dutch documentary photographer who followed several Nomadic cultures around the world for years. Also fashion collective ‘Das leben am Haverkamp’, which is founded by some of my old fashion classmates. I really like what they are doing and they inspire me to carry on. Maybe one day we can do a project together.

What is your plan for the future now that you have graduated?

I always hate this question... It feels very definite to talk about the future. I can only dream about it. I would love to have a little workshop with all kinds of presses so I can make special prints and books. I hope I can do more residencies and visit other countries. I went to Myanmar a few years ago and I really want to go there again to start a new project. But there are a lot of other things I dream about, for instance more collaborations like the one with Julia Dobber. I really like dreaming..

Ten years of tales from foreign lands from Paul Solberg

Ten Years in Pictures, Paul Solberg’s fifth photographic compendium, catalogues a decade of ethnographic encounters. Ahead of its launch, we caught up with Paul in his Manhattan home to discuss what this book represents for him and to reflects on ten years of recording life in his lens.

Ten Years in Pictures, Paul Solberg’s fifth photographic compendium, catalogues a decade of ethnographic encounters. From Hanoi to Cairo to Sicily to Jordan, we meet a startling diversity of artistic topography. The book reads as a world portrait where each part makes up a whole; each portrait stands alone with a poetic, poignant potency whilst weaving itself into a photographic tapestry of humanity. Solberg hones in on the intricacies in his anthropological portraits; choosing to capture the spontaneous, subtler details of cultural expression; but instead of cataloguing these subjects with a flat, documentary objectivity, he infuses these details with a joy, a poignancy and a simple reflectiveness. Through his photographs, we see “a world in which Solberg lives and wish we could all live”… we see a world in which we live in, but haven’t drawn our attention to. You are standing in Solberg’s shoes when looking at his photographs. The Moholy-Nagy new vision approach reframes his scenes and subjects from an alternative angle; encouraging us too to look on anew and afresh with, and though, his hungry, curious eyes.

Ten Years in Pictures represents ten years of collecting and curating tales from lenses and lives abroad. Ahead of its launch, Suzanna Swanson-Johnston caught up with Paul in his Manhattan home as he catches a breath between countries to discuss what this book represents for him and to reflects on ten years of recording life in his lens.

The book begins in 2004; the beginning of your professional photography career. Set the scene.

I have always been plagued by that chronic question of ‘Who are we? If you live with that, then you tend to be drawn to subjects like Anthropology, Philosophy, Photography out of a yearning for an answer. I come from a family where photography was a hobby; a predominant hobby, but a hobby, not a career. I ended up going to study Social Anthropology at university in South Africa and moved to N.Y.C. afterwards. As a kid in that city you can afford to be lost and that afforded me wonderful space in my twenties to live, and reflect. I met a director there and I assisted him on a film he was making, whilst ‘fluffing’ on Wall Street; talking to old ladies about their money in order to make enough of my own. Quintessentially Woody Allen. I moved to Nice when I was twenty-six to work for an ad agency. I loathed it. But I am adamant that being shown a lack of success and having it revealed to you what you hate and what you’re not good at, reveals to you what you are. The camera was always the most natural thing for me. But it wasn’t till my thirties, 2004, I was told I had the potential of it being my profession. I was offered a book deal, and with that came the promise of a career. I guess that tension, intensity, and desire has exploded into ten years of a densely packed period of work – which this book charts a selection of.

“you need a lifetime of experience to shape your eye”

Does marking this decade herald a different direction for your work now?

A photographer’s best work is usually in their later years; you need a lifetime of experience to shape your eye. Studying photography after you’ve learnt the technical process never made sense to me. Being thirsty and curious and learning about your subject grows your eye and that is the best school for taking pictures. I feel I’m still closer to the beginning of this whole process. It’s about paying attention, and I don’t always do. I would like to do a singular, biopic exploration of one subject at one point. My travel schedule is very disjointed so I’ve never in one place long enough. I am never that calculated about my career; I try to just stay relaxed, do my business and put it out there in the most honest way possible.

How have you seen the world evolve and change over the past ten years?

2004/2005/2006 were the last years where we were pre mass-media; people weren’t continually connected to technology. Now, we are all plugged in but entirely disconnected in being so; always partially listening or watching. We are so obsessive about documenting that we are never experiencing; we watch everything through the lenses of our iPhones.

Photography is an interesting dichotomy of that document / experience binary. I try to be as attentive to the world as I can and my photographs come out of that as an emblem of that experience. Thus, I work very candidly and organically.

The book is composed entirely of ‘found photos’; ‘found’ driving from Jordan to the Dead Sea and having a cup of tea with a man looking after fifteen orphans; ‘found’ as the light stroke perfectly on the surfers coming through Munich [City Surf]; ‘found’ when you happen to have discarded polaroid film in your camera and the sailors come off the boats [Service]; ‘finding’ ballroom dancers in the snow at the St. Peterburg market. This book was an exercise in of going through some of the thousands of images I’ve never looked back on and curating them. Half the book is unpublished material.

But I am highly aware that the cultures I have been recording might not be there in the next ten years, or five years even. Throughout my travels, the moment that has stuck with me the most is when I was dropped from a helicopter onto Alaska’s largest body of ice; the Bering Glacier. When you’re on a planet of ice, to hear the crackling and moan of the ice melting, you realize with a new clarity, the looming dilemma that the planet is literally disappearing from under our feet.

Having seen so much of the world, has your faith in humanity been inspired or disillusioned?

Travel turns you into an optimist and it teaches you that you know very little. The old adage “the more you know the more you don’t know” is really true. You go to different ends of the globe, and you learn, as cynical as one can be, people are generally good. I always think, why doesn’t CNN feature – in the same four story loop that they repeat over and over – an enlightening story about someone, somewhere, anywhere. They’re not hard to find, I know from experience; I’ve been welcomed into enough stranger’s homes. It’s hard to find a negative story on the road, why don’t you hear a good one occasionally from the news? I guess the sad story sells, otherwise we would hear them.

So that’s what travel does. It gives you the real news. The unedited news. The Egyptian cab driver that saw I was digging his Egyptian pop music he was playing as we drove through Luxor, and he finds me the next day, to give me the C.D. of music. I guess these small stories don’t have a lot of show-business to them. They’re more fireside stories. But that’s what I seek to capture ; the small details, the intricacies, the moments, the smaller narratives.

“It’s hard to find a negative story on the road, why don’t you hear a good one occasionally from the news?”

There is an anonymity to your work; thanks to the reluctance to provide a narrative, title or context and the new-vision-alternative angle of your lens...

I like to keep ambiguity. If there is a story, it is a collaboration with the viewer and I leave it up to them to impose their own decisions about who this person is and what their story is – I find that the interesting part. The identities are in the objects, not the names and the titles.

I find it far more fascinating when you hone in on the details. Under a microscope, suddenly the invisible becomes another world of mountains, rivers and new shapes.

What has travel taught you?

My travel process tends to be pretty unplanned; that’s how you find the spontaneous moments, you have to let the experiences happen through exploration. Crossing roads with no street lights in Hanoi; the orchestra of activity in streets dense with pandemonium and the weaving currents of Cairo; the sensation of dry in the Atacama desert; the solitude and the beautiful lifelessness; invitations into familiar strangers homes in Jordan; floating in the Dead Sea; the matte black of Lanzarote.

I appreciate how lucky I am to have had the opportunity to travel as much as I have; it’s something everyone should experience. You can read to escape your mind but it doesn’t compare to actually being there. I’ve stood in the spot where the bombs dropped on Vietnam and met the same family that still lives there. The faces, and connections, and people. It is being present in moments like that that is your world education. Travel builds empathy and expands perspective. A life of travel makes you realize everything is relative to your little world, so you don’t usually sweat the small stuff. You are humbled when you understand how provincial your concerns are.

Ten Years in Pictures Review

We interview Frankie Shea, founder of Moniker Art Fair

Moniker Art Fair returns for its sixth year, on October 15–18 at the Old Truman Brewery, having firmly established itself as London’s premiere event for contemporary art with its roots embedded in urban culture.

Moniker 2014

Moniker Art Fair returns for its sixth year, on October 15–18 at the Old Truman Brewery, having firmly established itself as London’s premiere event for contemporary art with its roots embedded in urban culture.

Building on the foundations of five years experience and it’s continued success, Moniker Art Fair will be again venue-sharing with London’s leading artist-led fair, The Other Art Fair, in what will be a showcase of independent and established talent all under one roof in East London’s iconic Old Truman Brewery.

This exciting spectacle will attract 14,000-plus visitors to the capital’s East End, forming one of the major satellite events of London’s Art Week when 60,000 visitors descend on the city to form an unparalleled international art audience. The partnership emphasises both fairs formidable reputations for showcasing artists operating under the radar of the traditional art establishment. Over a period of four days and across 21,000 sq. feet in The Old Truman Brewery’s impressive interior, this compelling combination promises to generate much interest and exposure this coming October.

BM - Why did you decide to start an art fair?

FS - The fair was started out of frustration.

I was running a gallery and representing several artists within the street art genre with great success. The artists I worked with had strong primary and secondary markets and I was keen to secure wider exposure for them but found it difficult to break into the UK art fair circuit. So in keeping with the ‘do-it-yourself’ street art ethos, I decided to form my own fair focusing on street art and its related subcultures.

BM - Does the name Moniker refer to the use of pseudonyms by many street artists?

FS – Yes. I was working with friend and artist Felix Berube (AKA Labrona), a Canadian freight train painter who told me all about Moniker Culture and the Hobos of America. I registered ‘Moniker Projects’ as a domain name before I even thought of the fair I think.

BM - What sets Moniker apart from all the other art fairs that are so ubiquitous this time of year?

FS – We’ve established ourselves as London’s premiere event for contemporary art with its roots embedded in urban culture. This is what ties the fair together and we have firmly put East London back on the art fair map in doing so. We’re an unpretentious fair, accessible and unpretentious. You won’t find many obscure pictures on white walls with gallery assistants glaring at you at our fair. Every day is fun, we are known for generating a friendly unintimidating art buying atmosphere. It’s become one of the highlights of London’s Art Week for many people.

BM - You have decided to accept Bitcoins this year, why is this?

Nick Walker, Decibel No.1 . Art of Patron space curated and produced by Moniker Projects

FS – A mixture of reasons. I met several people from the Bitcoin community this year who really sold the benefits of the digital currency to me. Plus they were genuinely nice people who welcome social change. I wanted to know more about the decentralised system so decided to curate a 50ft Bitcoin inspired installation that will integrate artworks by Ben Eine, Schooney and Toonpunk. Bitcoin will be accepted as valid tender throughout the fair, not necessarily because we believe Bitcoin will our saviour(!), but exploring possible alternatives to the current financial system is a good thing.

BM - How do you select the Moniker-represented artists?

FS – Initially I like their art and then I like them. Sometimes it happens the other way around, I like the artist and begin to understand their work and their paintings may grow more and more on me.

BM - Which are the most exciting artists that we should look out for at this years fair?

FS – I’m looking forward to seeing work by SA artist Kilmany-Jo Liversage, Betz from Etam Cru, French Street artist Bom.k who debuts at the fair and Apolo Torres. Legendary Bristol stencil artist Nick Walker will be exhibiting his brand new ‘smoke series’ body of work in the Art of Patron space along side multidisciplinary artist Lauren Baker. The Renaissance is Now installation is going to be off the wall.

Slow – Co – Ruption by Dineo Seehee Bopape

An interview with the South African artist on her first UK solo exhibition at the Hayward’s Project Space, London.

Dineo Seshee Bopape is one of South Africa’s most admired, unconventional artist. Her first UK solo exhibition at the Hayward’s Project Space, Southbank, can best be termed as surprising, unexpected, puzzling or wonderful that your brain cannot comprehend it. Too many gadgets going on at the same time. It’s like you are not supposed to grasp what the display is about? Comprehending the works isn’t really the idea here I gathered. You walk into the space and you are challenged by a tremor of everything but the kitchen sink. From sculptural installation with video montages to constant flash photography, two TV set with no pictures flipping between analogue and digital visuals, a machine mix and re-mix ear-splitting sound. What is more? Timber, bricks, mirrors and plants, form multifaceted and wobbly configurations, often across the walls and on grass floor of the gallery, alongside a fresh sculpture conceived especially for Hayward Gallery Project Space. The presentation is overwhelmingly imposing.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from why do you call me when you know i can’t answer the phone, 2012

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 10 minutes 42 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

DSB: I was born in 1981 in Polokwane, South Africa. I was born on a Sunday. If I were Ghanaian, my name would be akosua/akos for short. During the same year of my birth, the name ‘internet’ is mentioned for the first time Princess Diana of Britain marries Charles; AIDS is identified/created/named; Salman Rushdie releases his book “Midnight’s Children” bob Marley dies ‐ more events of the year of my birth are perhaps too many to have accounted for... I did my undergraduate studies in Art at Durban University of technology, South Africa, (2004), and attained my MFA from Columbia University, USA, in 2010. I work generally in a variety of mediums, mostly installation and video and drawing. My work has generally dealt with issues/ideas of representation so to speak... and memory, whilst some resist the pressure of having to mean something.

Here and now, what made you want to take part in Africa Utopia festival and what do you hope to pull off?

DSB: I was invited to take part. And what I hope to attain is to brush up my talking skills, I get often nervous when I speak in public, and often unsatisfied after because there is so much stuff that remains unsaid. Perhaps agreeing to participate is a chance for another rehearsal for the next time.

How would you describe your art? Is it redemptive, ethical or relative and political. And when putting together your installations what is your end goal?

DSB: It depends on who the viewer is I guess. It can be redemptive. Whilst in the process of making a work, goal posts changes. There is a freedom of sorts that comes with not having a strict goal. The goal is an unamiable thing.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from is i am sky, 2013

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 17 minutes 48 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from is i am sky, 2013

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 17 minutes 48 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

Talk to us about your Africa Utopia exhibition at the London Hayward Gallery project Space?

DSB: "Slow-co-ruption" is the title of the show. I was thinking about data corruption, the data of narrative, of memory, of liberal socio-politics, self, language, sense and order and all thatcorruption implies… rupture... An interruption of a memory/a file/a story... about politics of space and the metaphysics of being... A death… ‘Productive’ death…The show has 3 main works and 2 supports, so to speak. In the first room is “Same Angle, same lighting”, a mechanical sculptural work which I made in 2010 but is now in its 3rd incarnation. The first version had a light that was shining repetitively, back and forth on to a dark photograph (just looking over and over again). The 2nd version which I had shown in Cape town at Stevenson had a camera that was supposed to capture the information on a photograph and send it to a nearby monitor, but the machine kept on failing and what stood in the monitor with it was a pre-recorded video (showing the movement that was supposed to happen); an external memory of sorts…

(Flabbergasting response or what?) Rendered speechless.

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from is i am sky, 2013

Digital video, colour, sound

Duration: 17 minutes 48 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

And now in its 3rd reiteration in Slow-co-ruption, the camera sends information to several monitors/screens (hosts). The camera goes back and forth scanning the information off the paper (a scanned colour photocopy of picture of a lush garden from a garden and home magazine from the early 1990’s). This machine is hosted on and by these wooden supports and shop display things. Around “same angle, same lighting”- (the other supports) are several copies of video grass green/sky blue and also slow-co-ruption (stickers of flowers and eyes) the flowers are an almost random selection of native SA flowers and some from the garden image in same angle…. The eyes are those of an anonymous person and also those of philosophers Biko and Sobukwe who are also known for having written much about a need for rupture – both mental and spatial (so to speak). In the other rooms are the video “why do you call me when you know I can’t answer the phone” a piece from 2013 which is itself about the rupture of meaning or sense, a corruption or narrative. Whilst “Is I am sky” also speaks of a thing of absence, self-presence and of a kind of a metaphysical death to make a very insufficient summary…

Dineo Seshee Bopape

Video still from Grass Green, 2008

SD digital video, sound

Duration: 6 minutes 52 seconds

Photo credit: © Dineo Seshee Bopape. Courtesy of STEVENSON Cape Town, Johannesburg

Do you have a favourite piece from this exhibition and what next for DSB?

DSB: Not really, I love the different pieces differently...but currently I must say I am most excited about the "slow-co-ruption" stickers. On what next? I would like to show my work more on the African continent (abroad too), I would like to grow as an artist, to clarify my thoughts, for my work to be sharper, to continue being curious and continue to play... also to share with others... to remain healthy and able.

We meet fabric illusionist Yvette Peek

The ArtEZ design alumni blew everyone away with her graduation collection, sending illusional masterpieces down the catwalk. Check out the interview.

All keep track of upcoming designer Yvette Peek. The ArtEZ design alumni blew everyone away with her graduation collection, sending illusional masterpieces down the catwalk. As curious as we are, we had a talk with her about the story behind her first collection, her admiration for strong women with non-conforming elegance and being the assistant designer of Sharon Wauchob.

What made you realize you wanted to be a designer?

My biggest source of inspiration is my grandmother. When I was a little girl, she taught me how to sew. That led to her teaching me embroidery techniques and pattern making. We even stitched my first designs together.

What do you think are your biggest assets as a designer?

As a designer I challenge myself to find the unexpected in materials and textiles and I made that into my greatest strength. When I design clothing I always have a strong woman in mind, with non-conforming elegance and a luxurious approach to colour and fabric. My graduation collection is based on the insomnia drawings of Louise Bourgeois. One of the strongest and most inspiring women I have ever known.

Before you started with the collection, did you already know the outcome of the design concept?

I went to the exhibition of Bill Viola during my internship in Paris. This was one of the most exhilarating exhibitions I have ever seen. My eye caught on of his illusional art pieces ‘Veiling’ of Bill Viola. In a dark space, an unfocussed film of a man is projected through 10 translucent sheets of fabric, growing paler and larger towards the centre. Two projectors at opposite ends of the space face each other and project images into the layers of material. I became fixated on this video installation. And from that moment on I knew that I wanted to recreate that illusional effect with different kind of layers fabric in my collection. The elements of shape-shifting developed later on, during my drape sessions. After a few drape sessions I came to the idea that my collection had to represents the brain that is experiencing insomnia, and that’s where the insomnia drawings came in.

You interpreted insomnia with fabrics where Louise Bourgeois did the same thing with pencil. Why is it that your collection exists of tints of black, grey and white, while bourgeois’ work consists of colour?

The type of woman I made this collection for is elegant, unpredictable and psychotic. I have used darker tones to create that psychotic vibe. And the best way to create an unpredictable illusion through different layers is to use tints of black and grey.

Can you tell us a bit more about the design process behind the collection?

Quality of fabric and craftsmanship are my most important values when designing. Therefore I won’t be looking at the clock when working on my designs. My collection consists of a lot of different crafts that have to be meticulously conducted. One look required an embroidered top that consists of 460 small pieces of springs that I have formed in circles, and those springs and beads are all embroidered by hand. This took my approximately three weeks. The two last looks in my collection consist of 22 meters of tulle per outfit, all hand-printed with markers, and 4.5 meters of printed plastic. From of all the time I spent working on my collection, those looks were the ones that took up the most time.

You're working as an assistant designer for Sharon Wauchob now. How did that happen and what do you admire about her work?

I worked as an intern for Sharon Wauchob two years ago. During my internship I was assigned as assistant textile/embroideries designer. This was one of the best learning experiences I had so far as Sharon gave me a lot of opportunities to develop myself. After my internship I went back to school for my final year but I stayed in contact with her and I always came back to Paris to help the team during Paris Fashion Week. Sharon is a consistently talented designer who creates thoughtfully engineered garments. I admire her strong detail-focused aesthetic. The way she uses traditional techniques and delicate fabrics in her collection inspires me.

How do you see your career developing from now on?

I would like to gain more experience within the field of design. I hope to get the opportunity to learn a lot from Sharon Wauchob over the next years. It would also be interesting to develop myself within another creative luxury brand with a focus on textiles, but we should not jump to conclusions. You never know what happens and I am looking forward to every new opportunity!

Artists and Scientists at Music Tech Fest

The exciting formula for championing future creative and technological collaboration in music. We interview Andrew Dubber, Music Tech Fest's Director.

Soft Revolvers by Myriam Bleau

Andrew Dubber, Music Tech Fest’s director, explains to me the freedom Music Tech Fest fosters in joining creative musicians and technological minds in an all-inclusive environment – the aim is to ultimately liberate the music technology scene and revel in the mayhem that ensues.

How and why was 'Music Tech Fest' conceived and what developments has it gone through to make it the internationally-reaching community it is today?